Last week, Google’s Threat Analysis Group published details around what appears to be APT activity targeting, among others, Mac users visiting Hong Kong websites supporting pro-democracy activism. Google’s report focused on the use of two vulnerabilities: a zero day and a N-day (a known vulnerability with an available patch).

By the time of Google’s publication both had, in fact, been patched for some months. What received less attention was the malware that the vulnerabilities were leveraged to drop: a backdoor that works just fine even on the latest patched systems of macOS Monterey.

Google labelled the backdoor “Macma”, and we will follow suit. Shortly after Google’s publication, a rapid triage of the backdoor was published by Objective-See (under the name “OSX.CDDS”). In this post, we take a deeper dive into macOS.Macma, reveal further IoCs to aid defenders and threat hunters, and speculate on some of macOS.Macma’s (hitherto-unmentioned) interesting artifacts.

How macOS.Macma Gains Persistence

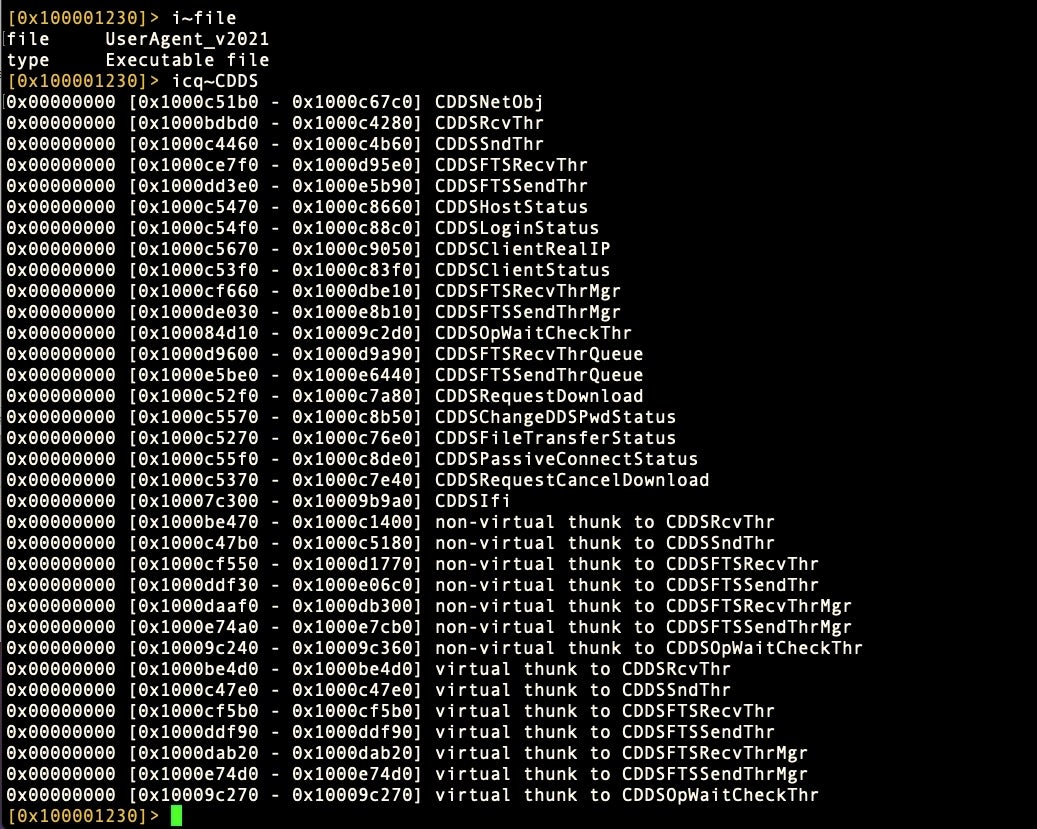

Thanks to the work of Google’s TAG team, we were able to grab two versions of the backdoor used by the threat actors, which we will label UserAgent 2019 and UserAgent 2021. Both are interesting, but arguably the earlier 2019 version has greater longevity since the delivery mechanism appears to work just fine on macOS Monterey.

UserAgent 2019 is a Mach-O binary dropped by an application called “SafariFlashActivity.app”, itself contained in a .DMG file (the disk image sample found by Google has the name “install_flash_player_osx.dmg”). UserAgent 2021 is a standalone Mach-O binary and contains much the same functionality as the 2019 version along with some added AV capture capabilities. This version of macOS.Macma is installed by a separate Mach-O binary dropped when the threat actors leverage the vulnerabilities described in Google’s post.

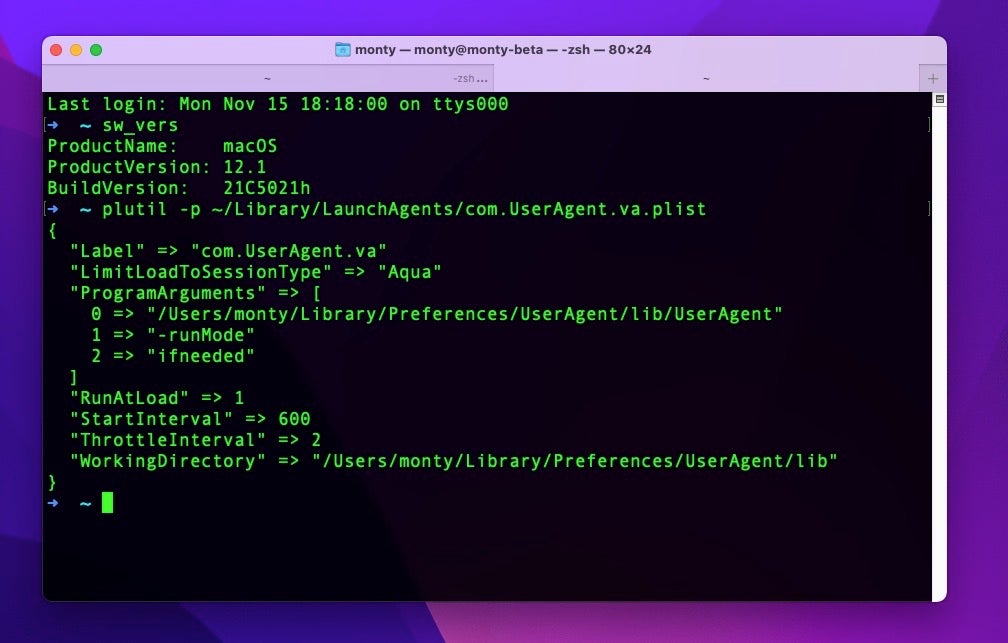

Both versions install the same persistence agent, com.UserAgent.va.plist in the current user’s ~/Library/LaunchAgents folder.

The property list is worth pausing over as it contains some interesting features. First, aside from the path to the executable, we can see that the persistence agent passes two arguments to the malware before it is run: -runMode, and ifneeded.

The agent also switches the current working directory to a custom folder, in which later will be deposited data from the separate keylogger module, among other things.

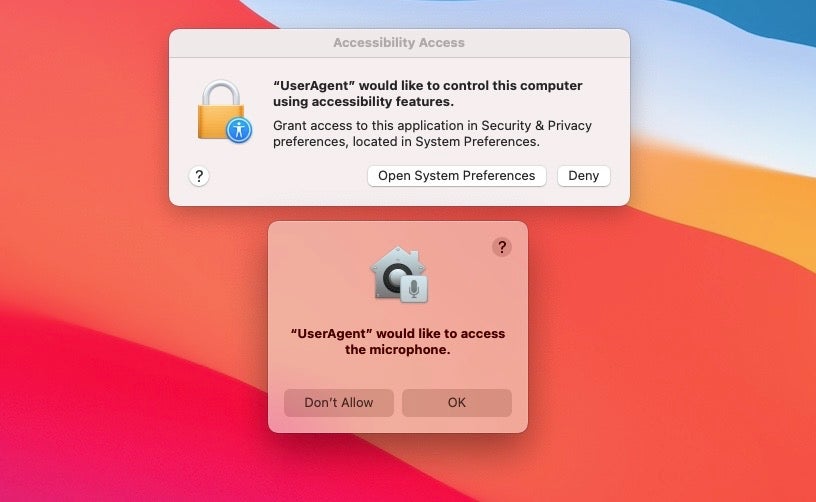

We find it interesting that the developer chose to include the LimitLoadToSessionType key with the value “Aqua”. The “Aqua” value ensures the LaunchAgent only runs when there is a logged in GUI user (as opposed to running as a background task or running when a user logs in via SSH). This is likely necessary to ensure other functionality, such as requesting that the user gives access to the Microphone and Accessibility features.

However, since launchd defaults to “Aqua” when no key is specified at all, this inclusion is rather redundant. We might speculate that the inclusion of the key here suggests the developer is familiar with developing other LaunchAgents in other contexts where other keys are indeed necessary.

Application Bundle Confusion Suggests A “Messy” Development Process

Since we are discussing property lists, there’s some interesting artifacts in the SafariFlashActivity.app’s Info.plist, and that in turn led us to notice a number of other oddities in the bundle executables.

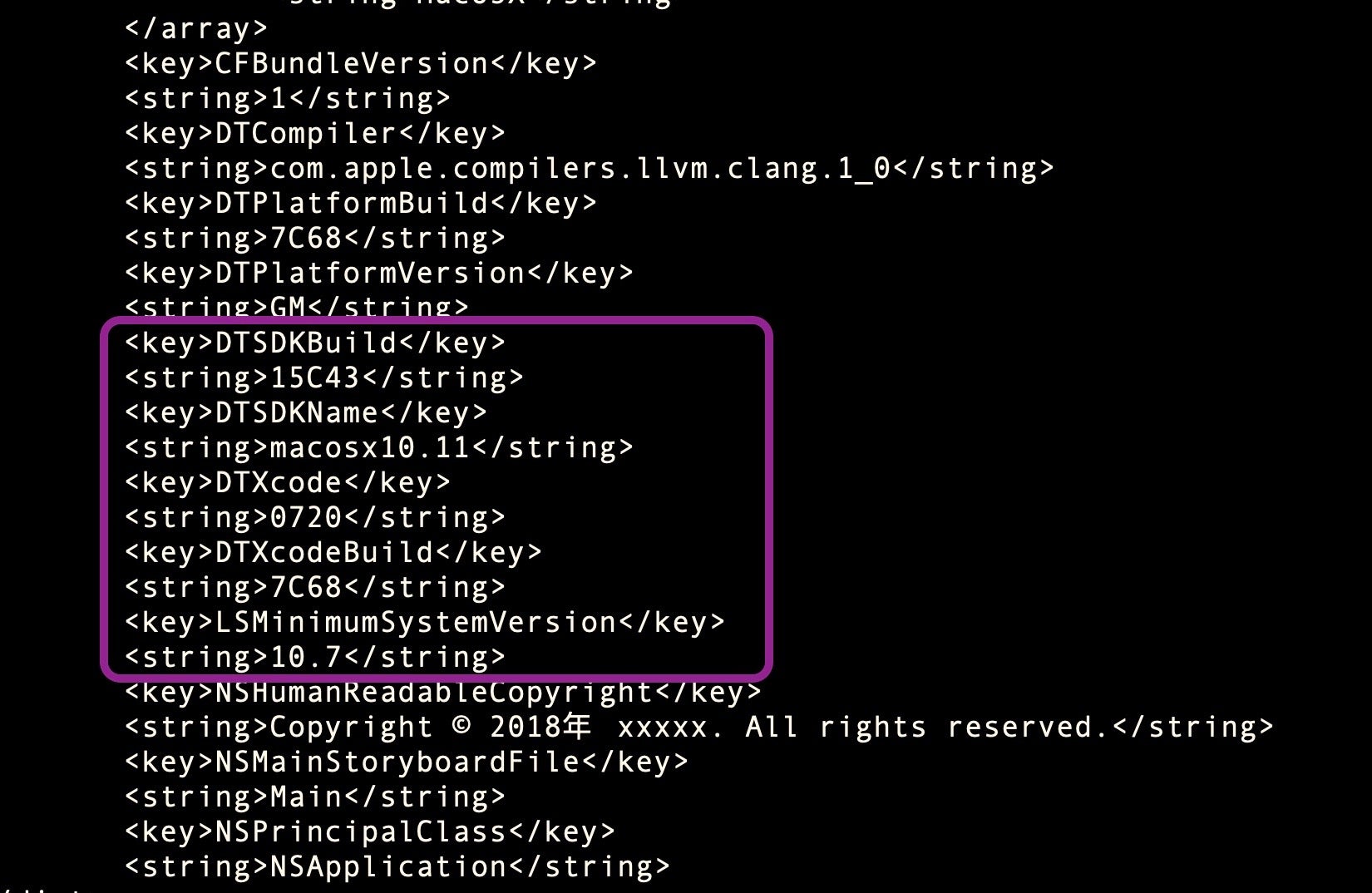

One of the great things about finding malware built into a bundle with an Info.plist is it gives away some interesting details about when, and on what machine, the malware was built.

In this case, we see the malware was built on an El Capitan machine running build 15C43. That’s curious, because build 15C43 was never a public release build: it was a beta of El Capitan 11.2 available to developers and AppleSeed (Apple beta testers) briefly around October to November 2015. On December 8th, 2015, El Capitan 11.2 was released with build number 15C50, superseding the previous public release of 11.1, build 15B42 from October 21st.

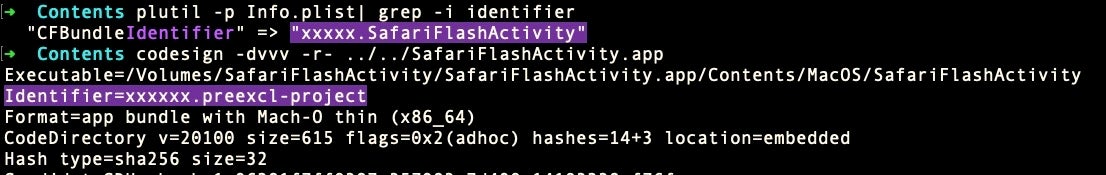

At this juncture, let’s note that the malware was signed with an ad hoc signature, meaning it did not require an Apple Developer account or ID to satisfy code signing requirements.

Therein lies an anomaly: the bundle was signed without needing a developer account, but it seems that the macOS version used to create this version of macOS.Macma was indeed sourced from a developer account. Such an account could possibly belong to the author(s); possibly be stolen, or possibly acquired with a fake ID. However, the latter two scenarios seem inconsistent with the ad hoc signature. If the developer had a fake or stolen Apple ID, why not codesign it with that for added credibility?

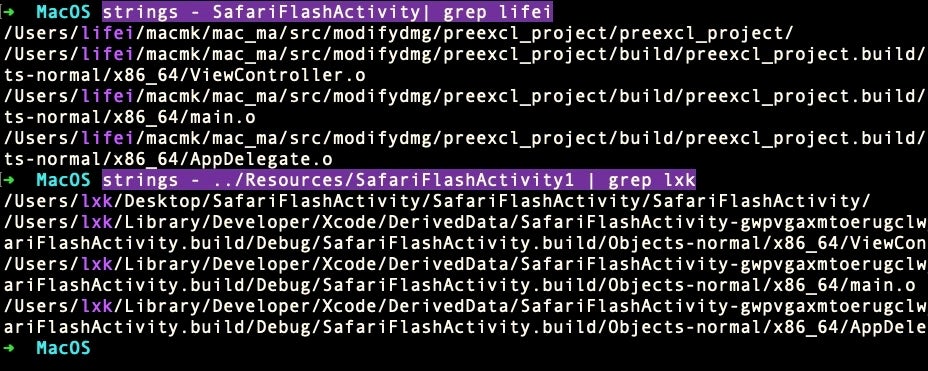

While we’re speculating about the developer or developers’ identities, two other artifacts in the bundle are worthy of mention. The main executable in ../MacOS is called “SafariFlashActivity” and was apparently compiled on Sept 16th, 2019. In the ../Resources folder, we see what appears to be an earlier version of the executable, “SafariFlashActivity1”, built some nine days earlier on Sept 7th.

While these two executables share a large amount of code and functionality, there are also a number of differences between them. Perhaps the most intriguing are that they appear – by accident or by design – to have been created by two entirely different users.

The user account “lifei” (speculatively, Li Fei, a common-enough Chinese name) seems to have replaced the user account “lxk”. Of course, it could be the same person operating different user accounts, or two entirely different individuals building separately from a common project. Indeed, there are sufficiently large differences in the code in such a short space of time to make it plausible to suggest that two developers were working independently on the same project and that one was chosen over the other for the final executable embedded in the ../MacOs folder.

Note that in the “lifei” builds, we see both the use of “Mac_Ma” for the first time, and “preexcel” — used as the team identifier in the final code signature. Neither of these appear in the “lxk” build, where “SafariFlashActivity” appears to be the project name. This bifurcation even extends to an unusual inconsistency between the identifier used in the bundle and that used in the code signature, where one is xxxxx.SafariFlashActivity and the other is xxxxxx.preexcl-project.

In any case, the string “lifei” is found in several of the other binaries in the 2019 version of macOS.Macma, whereas “lxk” is not seen again. In the 2021 version, both “lifei” and “lxk” and all other developer artifacts have disappeared entirely from both the installer and UserAgent binaries, suggesting that the development process had been deliberately cleaned up.

Finally, if we return to the various (admittedly, falsifiable) compilation dates found in the bundle, there is another curiosity: we noted that the malware appears to have been compiled on a 2015 developer build of macOS, yet the Info.plist has a copyright date of 2018, and the executables in this bundle were built well-over 3 years later in September 2019 according to the (entirely manipulatable) timestamps.

What can we conclude from all these tangled weeds? Nothing concrete, admittedly. But there do seem to be two plausible, if competing, narratives: perhaps the threat actor went to extraordinary, and likely unnecessary, lengths to muddle the artifacts in these binaries. Alternatively, the threat actor had a somewhat confused development process with more than one developer and changing requirements. No doubt the truth is far more complex, but given the nature of the artifacts above, we suspect the latter may well be at least part of the story.

For defenders, all this provides a plethora of collectible artifacts that may, perhaps, help us to identify this malware or track this threat actor in future incidents.

macOS.Macma – Links To Android and Linux Malware?

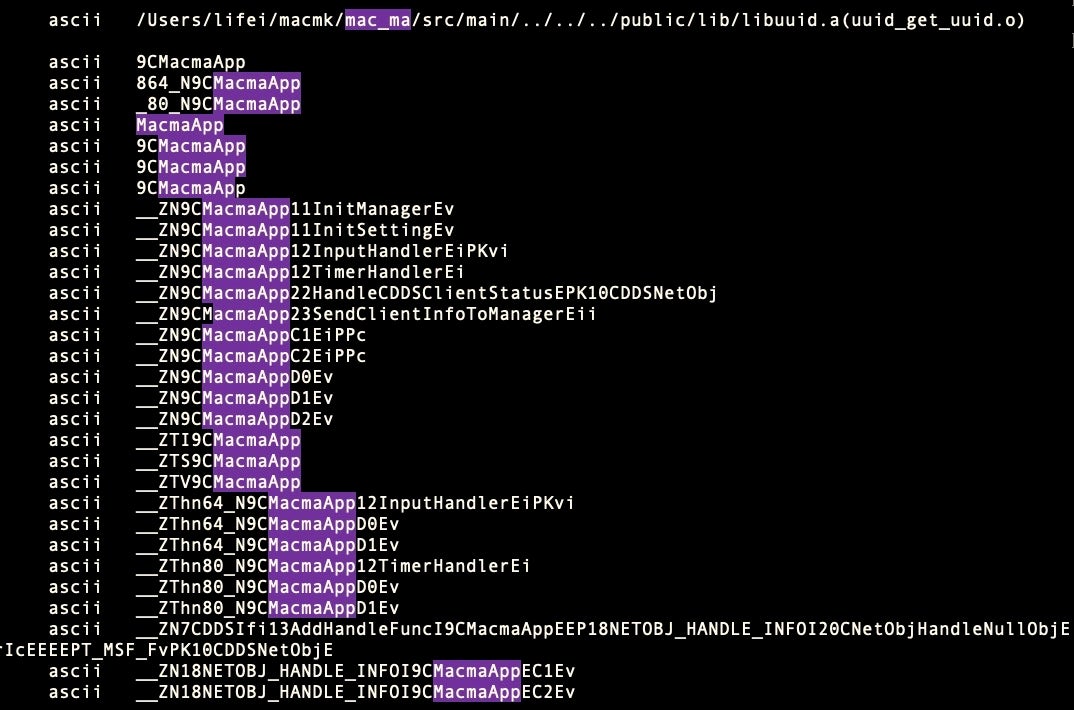

Things start to get even more interesting when we take a look at artifacts in the executable code itself. As we noted in the introduction, an early report on this malware dubbed it “OSX.CDDS”. We can see why. The code is littered with methods prefixed with CDDS.

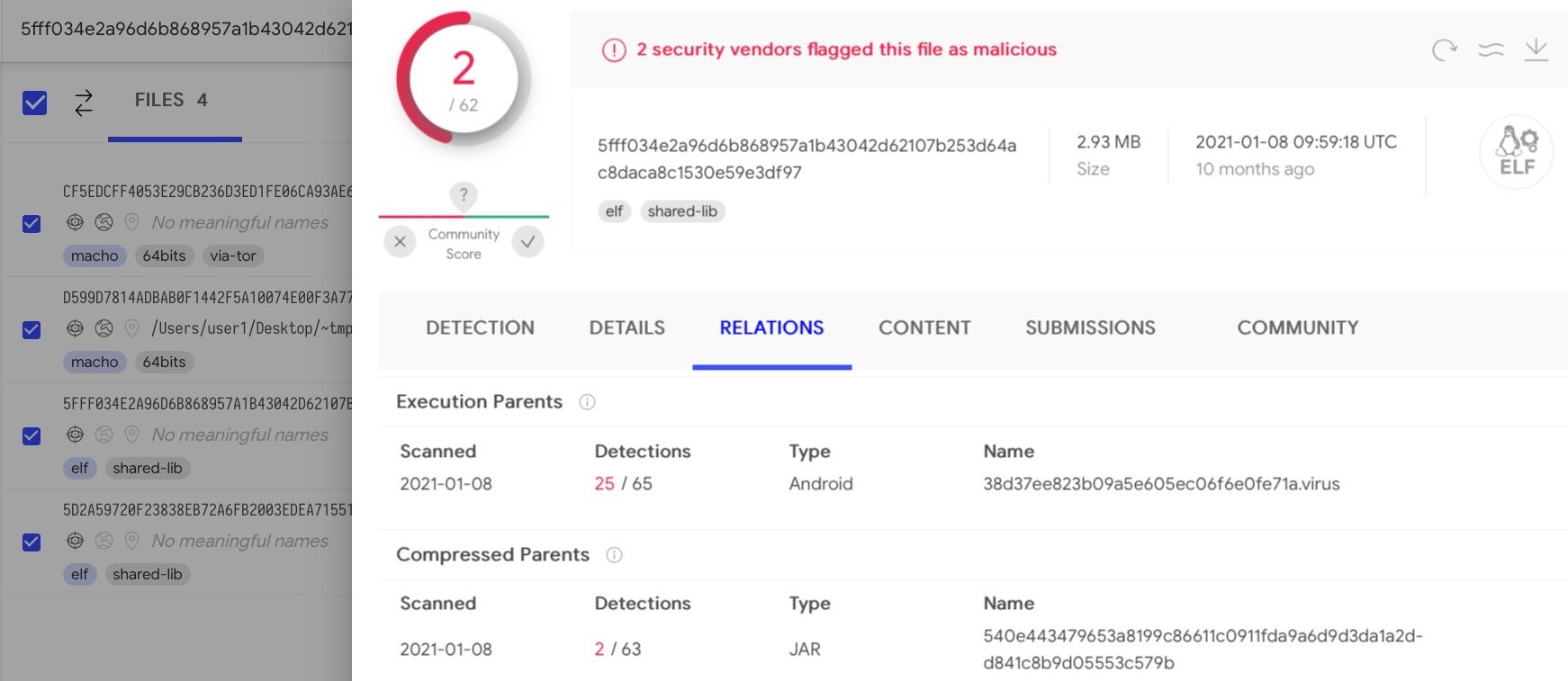

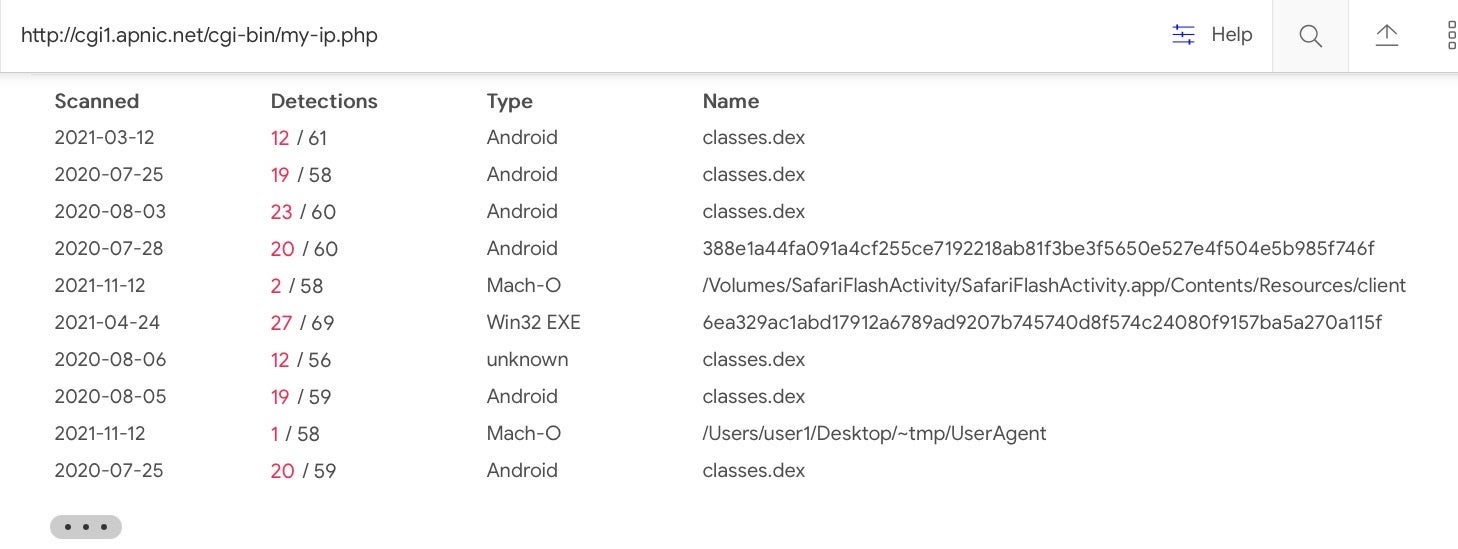

That code, according to Google TAG, is an implementation for a DDS – Data Distribution Service – framework. While our searches turned up blank trying to find a specific implementation of DDS that matched the functions used in macOS.Macma, we did find other malware that uses the same framework.

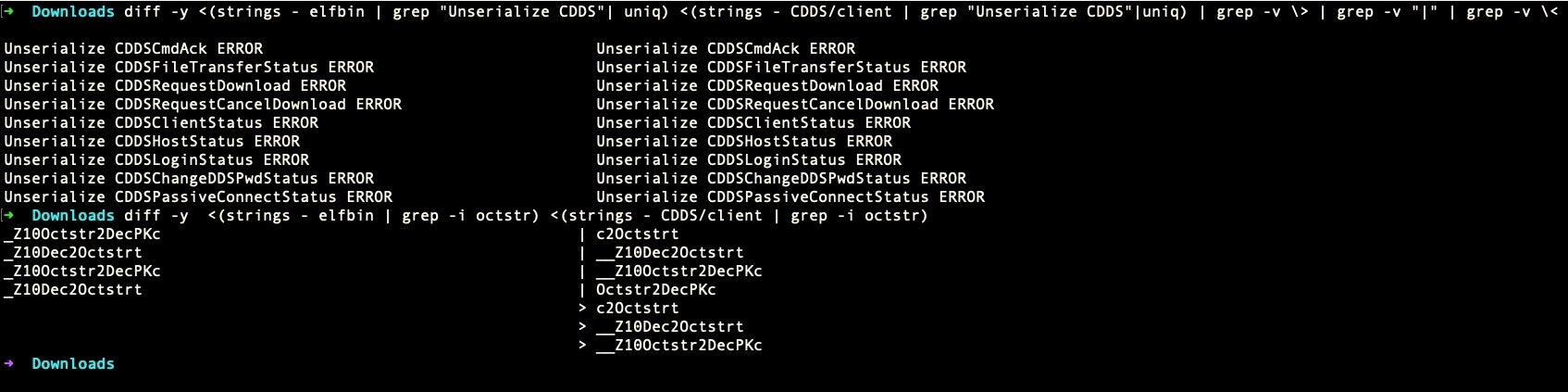

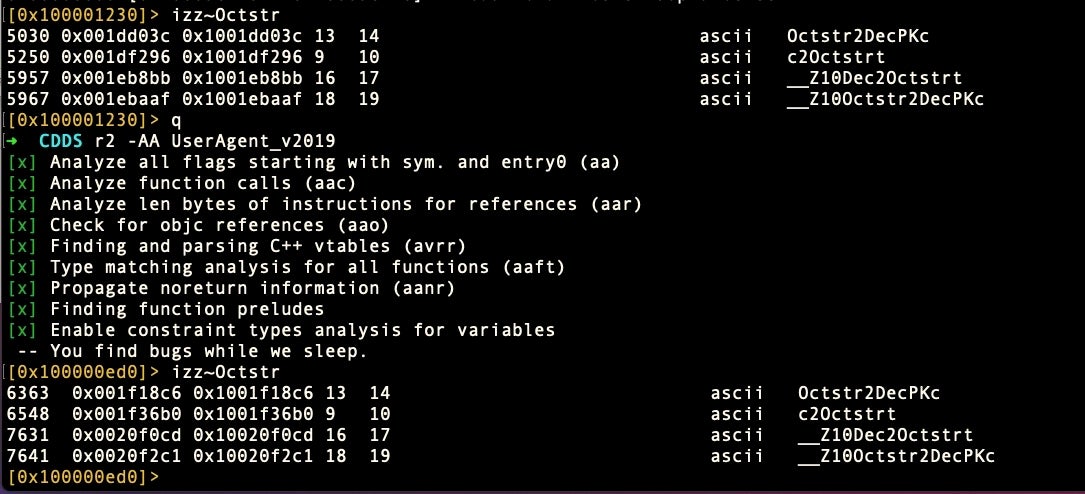

These ELF bins and both versions of macOS.Macma’s UserAgent also share another commonality, the strings “Octstr2Dec” and “Dec2Octstr”.

These latter strings, which appear to be conversions for strings containing octals and decimals, may simply be a matter of coincidence or of code reuse. The code similarities we found also have links back to installers for the notorious Shedun Android malware.

In their report, Google’s TAG pointed out that macOS.Macma was associated with an iOS exploit chain that they had not been able to entirely recover. Our analysis suggests that the actors behind macOS.Macma at least were reusing code from ELF/Android developers and possibly could have also been targeting Android phones with malware as well. Further analysis is needed to see how far these connections extend.

Macma’s Keylogger and AV Capture Functionality

While the earlier reports referred to above have already covered the basics of macOS.Macma functionality, we want to expand on previous reporting to reveal further IoCs.

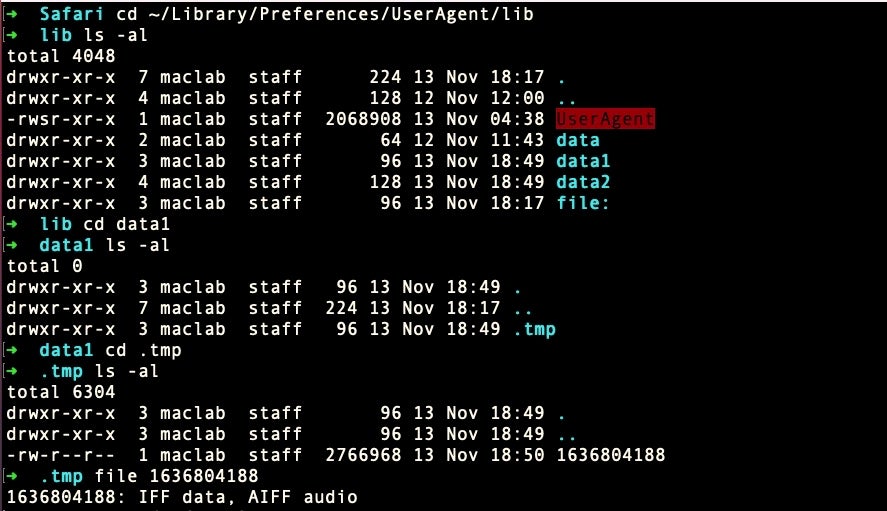

As previously mentioned, macOS.Macma will drop a persistence agent at ~/Library/LaunchAgents/com.UserAgent.va.plist and an executable at ~/Library/Preferences/lib/UserAgent.

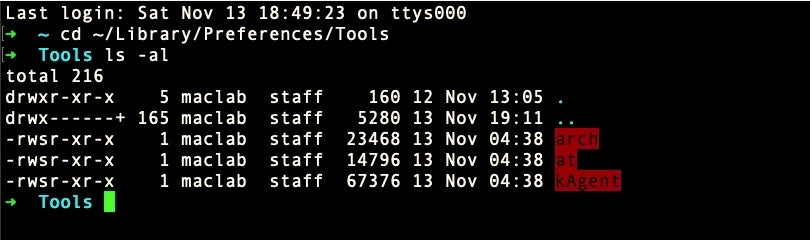

As we noted above, the LaunchAgent will ensure that before the job starts, the executable’s current working directory will be changed to the aforementioned “lib” folder. This folder is used as a repository for data culled by the keylogger, “kAgent”, which itself is dropped at ~/Library/Preferences/Tools/, along with the “at” and “arch” Mach-O binaries.

The kAgent keylogger creates text files of captured keystrokes from any text input field, including Spotlight, Finder, Safari, Mail, Messages and other apps that have text fields for passwords and so on. The text files are created with Unix timestamps for names and collected in directories called “data”.

We also note that this malware reaches out to a remote .php file to return the user’s IP address. The same URL has a long history of use.

http://cgi1.apnic.net/cgi-bin/my-ip.php

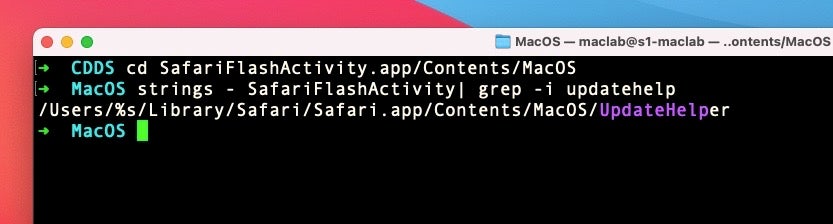

Finally, one further IoC we noted in the ../MacOS/SafariFlashActivity “lifei” binary that never appeared anywhere else, and we also did not see dropped on any of our test runs, was:

/Users/%s/Library/Safari/Safari.app/Contents/MacOS/UpdateHelper

This is worth mentioning since the target folder, the User’s Library/Safari folder, is TCC protected since Mojave. For that reason, any attempt to install there would fall afoul of current TCC protections (bypasses notwithstanding). It looks, therefore, like a remnant of the earlier code development from El Capitan era, and indeed we do not see this string in later versions. However, it’s unique enough for defenders to watch out for: there’s never any legitimate reason for an executable at this path to exist on any version of macOS.

Conclusion

Catching APTs targeting macOS users is a rare event, and we are lucky in this instance to have a fairly transparent view of the malware being dropped. Regardless of the vector used to drop the malware, the payload itself is perfectly functional and capable of exfiltrating data and spying on macOS users. It’s just another reminder, if one were needed, that simply investing in a Mac does not guarantee you safe passage against bad actors. This may have been an APT-developed payload, but the code is simple enough for anyone interested in malfeasance to reproduce.

Indicators of Compromise

SHA1

000830573ff24345d88ef7916f9745aff5ee813d; UserAgent 2021 payload, Mach-O

07f8549d2a8cc76023acee374c18bbe31bb19d91; UserAgent 2019, Mach-0

0e7b90ec564cb3b6ea080be2829b1a593fff009f; (Related) ELF DYN Shared object file

2303a9c0092f9b0ccac8536419ee48626a253f94; UserAgent 2021 installer, Mach-0

31f0642fe76b2bdf694710a0741e9a153e04b485; SafariFlashActivity1, Mach-0

734070ae052939c946d096a13bc4a78d0265a3a2; (Related) ELF DYN Shared object file

77a86a6b26a6d0f15f0cb40df62c88249ba80773; at, Mach-0

941e8f52f49aa387a315a0238cff8e043e2a7222; install_flash_player_osx.dmg, DMG

b2f0dae9f5b4f9d62b73d24f1f52dcb6d66d2f52; client, Mach-0

b6a11933b95ad1f8c2ad97afedd49a188e0587d2; SafariFlashActivity, Mach-0

c4511ad16564eabb2c179d2e36f3f1e59a3f1346; arch, Mach-0

f7549ff73f9ce9f83f8181255de7c3f24ffb2237; SafariFlashActivityInstall, shell script

File Paths

~/Library/Preferences/Tools/at

~/Library/Preferences/Tools/arch

~/Library/Preferences/Tools/kAgent

~/Library/LaunchAgents/com.UserAgent.va.plist

~/Library/Preferences/UserAgent/lib/Data/

~/Library/Preferences/UserAgent/lib/UserAgent

~/Library/Safari/Safari.app/Contents/MacOS/UpdateHelper

Identifiers

xxxxx.SafariFlashActivity

xxxxxx.preexcl.project