It wasn’t so long ago that malware authors, much like software developers, were concerned about the size of their code, aiming to keep it as small and compact as possible. Small binaries are less noticeable and can be slipped inside other files or shipped in benign code, attachments and even images. Smaller executables take up less space on disk, are faster to transfer over the wire, and – if they’re written efficiently – can execute their malicious instructions with less tax on the host CPU. In days of small disk drives, slow network connections and underpowered chips, such concerns made good sense and helped malware to avoid detection.

In today’s computer environments, however, storage, bandwidth and processor power are rarely in short supply, and as a result both legitimate programs and malware have increased greatly in size.

While malware executables of several megabytes are now so common they are hardly worthy of mention, some recent malicious programs have taken the invitation to bloat to a new extreme. Malware binaries weighing in at 50MB or more are now widely in use by macOS malware authors, and binaries over 100MB can also be found in some campaigns, typically those involving cryptominers. Such massive file sizes can cause detection problems for some kinds of AV solutions and create triage and reversing challenges for malware analysts.

In this post, we dig into the phenomenon of massive malware binaries on macOS, explaining why they are becoming more common, the problems they cause for detection and analysis, and how defenders can successfully deal with them.

How Widespread are Large macOS Malware Binaries?

It is possible to get a feel for how common large malicious binaries are by hunting in public malware repositories like VirusTotal and filtering by size. For example, if we search for Mach-O binaries over 35MB recognized as malware by 5 or more vendors, the search today returns 524 hits.

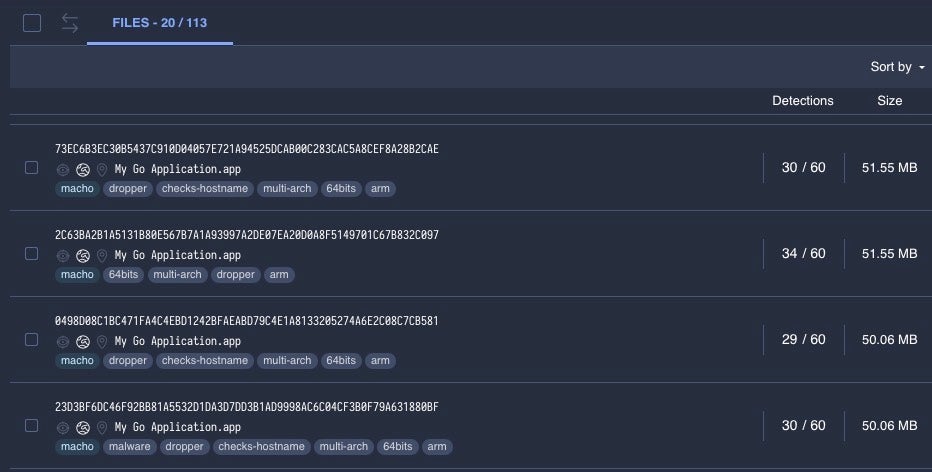

Increasing the file size to 50MB or more returns 113 hits, with many of the files returned being samples of Atomic Stealer.

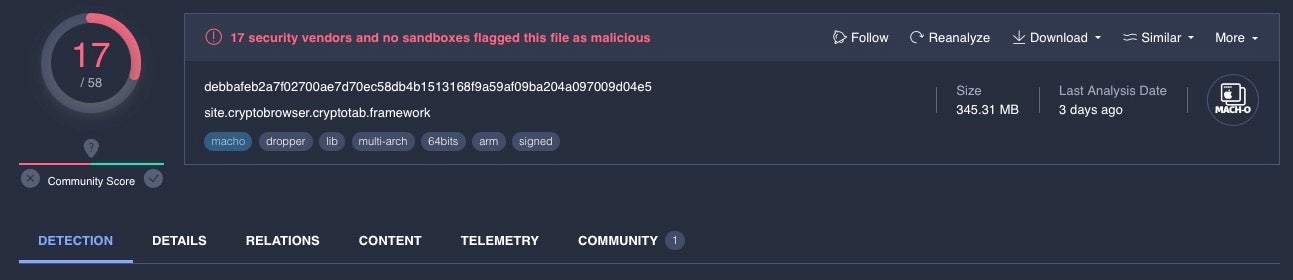

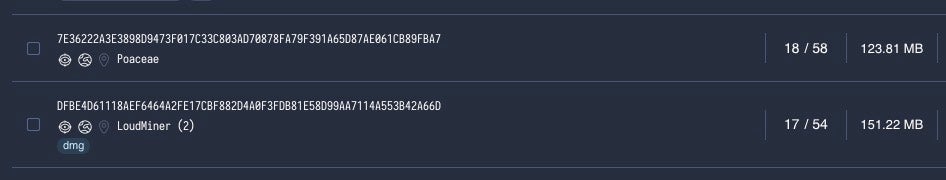

Around 7 samples in the 75MB and 100MB size range are examples of OSX.EvilQuest malware. Adjusting our search for file sizes of 100MB returns over 20 files with five or more vendors detecting as malware; many of these are miners, including a coinminer executable weighing in at 345 MB.

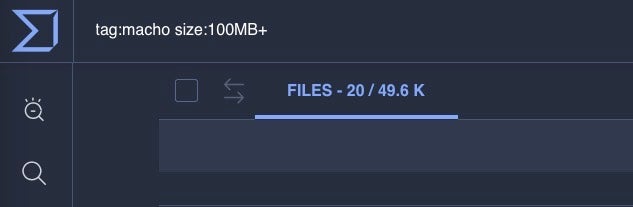

However, the problem is wider than just those files that vendors currently recognize as malware. Both detection solutions and analysts have to determine whether an unknown sample is suspicious or malicious, and if we look at the number of Mach-O binaries on VT in general that are over 35MB, we find almost 100,000 samples, with the number of samples over 100MB currently at almost 50,000.

We can even find a single Mach-O binary on VirusTotal with a file size of 600MB. Are there individual binaries larger than that? Almost certainly, but VirusTotal has a file size upload limit of 650MB, so above that we have a data blindspot for both legitimate and malicious files.

From the data we do have, it is clear large executables are a widespread phenomenon, but why are threat actors turning to bloated binaries and what problems do they cause for enterprise security?

Why Are Threat Actors Turning to Supersized Binaries?

There are a number of reasons why threat actors may choose to distribute malware in oversized binaries. Some large binaries such as cryptominers like BirdMiner (aka LoudMiner) are a result of bundling emulation environments such as QEMU in the malware.

Other large binaries are caused by using cross-platform programming languages like Go and Rust. In order to ensure these programs will run on the intended platform, the runtime, libraries and all other dependencies are compiled into the final payload.

In addition, Apple’s switch to ARM from Intel has resurrected the Universal/FAT binary format, in which two architectures are now compiled into a single binary to ensure that the same program will work regardless of whether the user runs it on an Intel Mac or an Apple silicon Mac. Any binary compiled into the Universal format is effectively doubled in size.

As we shall see in the next section, in some cases threat actors may simply bloat files with junk code to defeat file scanners with file size limits or to thwart analysis by malware researchers.

What Problems Do Outsized Binaries Cause For Detection and Analysis?

Massive individual binaries are a relatively recent phenomenon and they cause a headache for traditional AV scanners that rely on either computing a file’s hash or scanning it for malicious content. The larger the binary the longer it takes to scan, and when scanning across numerous files on a file system, the end result can be a sluggish, unresponsive system as the AV software increasingly hogs the host CPU to complete its task.

The performance problems associated with file scanning are historically one of the most oft-cited reasons for complaints from users and something that the industry has attempted to solve in various ways.

One typical solution employed by many AV scanners is to limit the maximum file size the scanner will accept. In the days when few legitimate programs reached more than 20MB that may have seemed like an acceptable compromise, but given today’s bloated binaries, that’s clearly no longer viable: it would mean that a lot of known malware would go undetected. Threat actors have even been known to bloat files with junk code precisely to defeat file size limits of scanners and malware repositories like VirusTotal, which as we noted above has a max file size upload limit of 650MB.

Massive files are not just a problem for detection software, but also for researchers, reverse engineers and malware analysts. With tens of megabytes of code to analyze, most of which is benign, junk or part of a standard runtime like Go, analysts can have a difficult time identifying exactly which parts of a binary are malicious. This can hamper efforts to find other, possibly undetected, malware samples using the same or similar code and allow threat actors to extend their campaigns without detection.

How to Detect Malware Hidden Inside Massive Binaries

Fortunately, there are solutions to the problem of massive binaries both for detection and analysis. The problems inherent in relying solely on file scanning have been well understood by vendors such as SentinelOne and were part of the paradigm shift that caused such solutions to adopt behavioral detection.

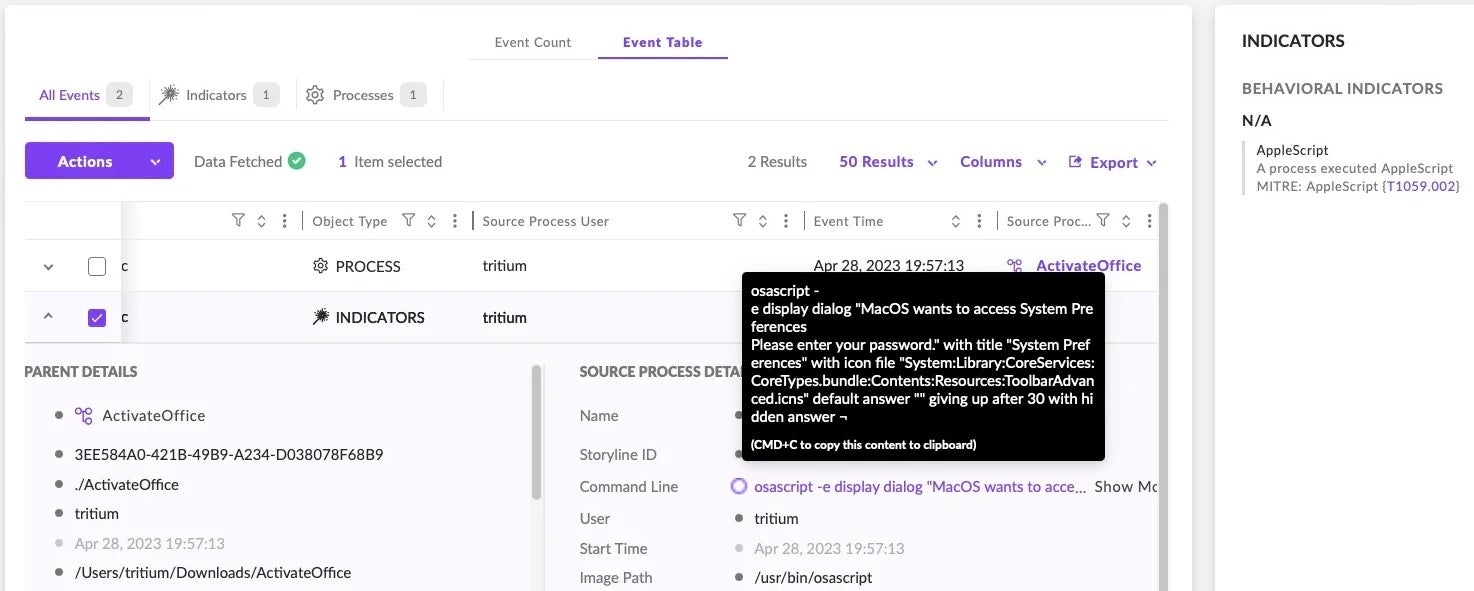

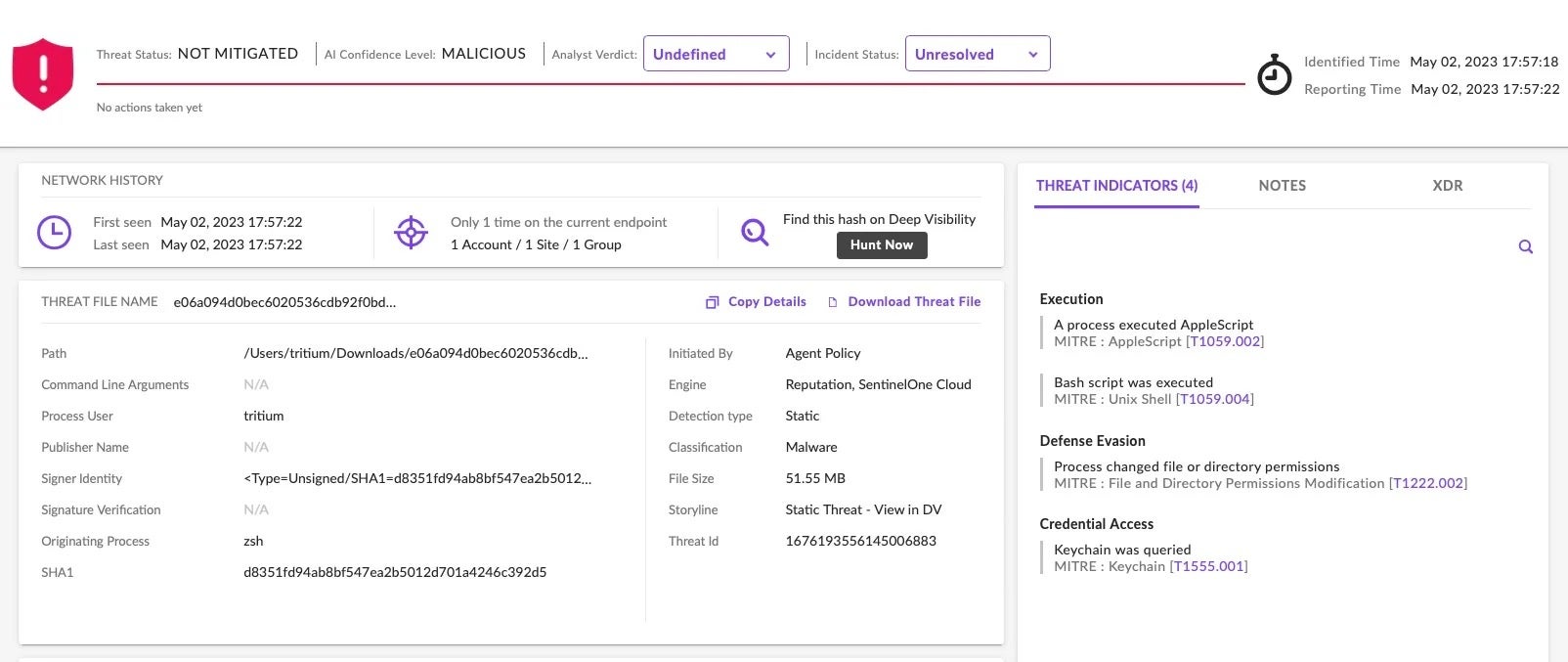

In contrast to a file scanning engine, a behavioral engine examines what a binary does when it is executed rather than examining the file’s content prior to execution. A behavioral approach allows a solution to avoid scanning large amounts of files or files of large sizes and instead determines whether an execution process is involved in malicious activity. Solutions like SentinelOne can thus detect and kill malware regardless of how it is packaged or how large the file is.

Security software that combines multiple detection mechanisms including behavioral and machine learning detection engines is now the standard for enterprise security.

How to Analyze Large macOS Malware Binaries

Large binaries present malware analysts with a number of challenges. In this section, we will briefly describe a useful technique for finding interesting code among hundreds of thousands of lines of disassembly leveraging YARA and radare2.

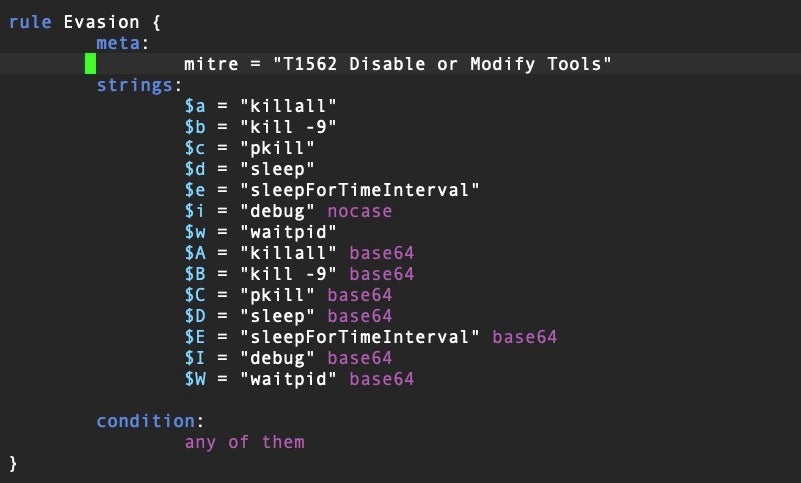

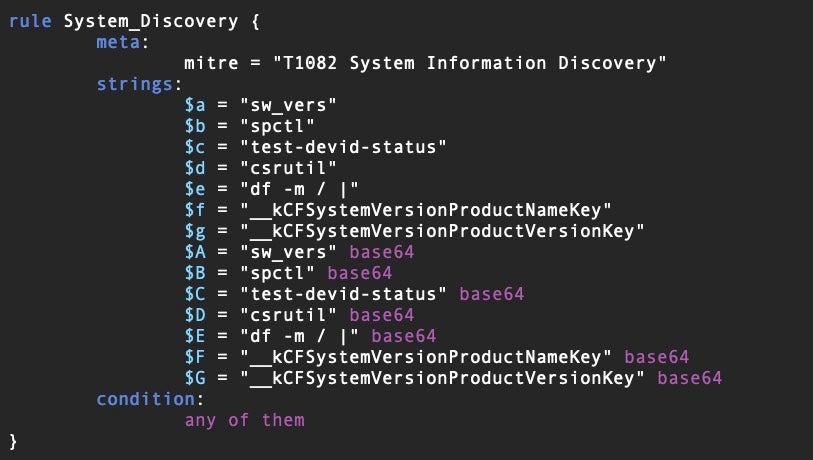

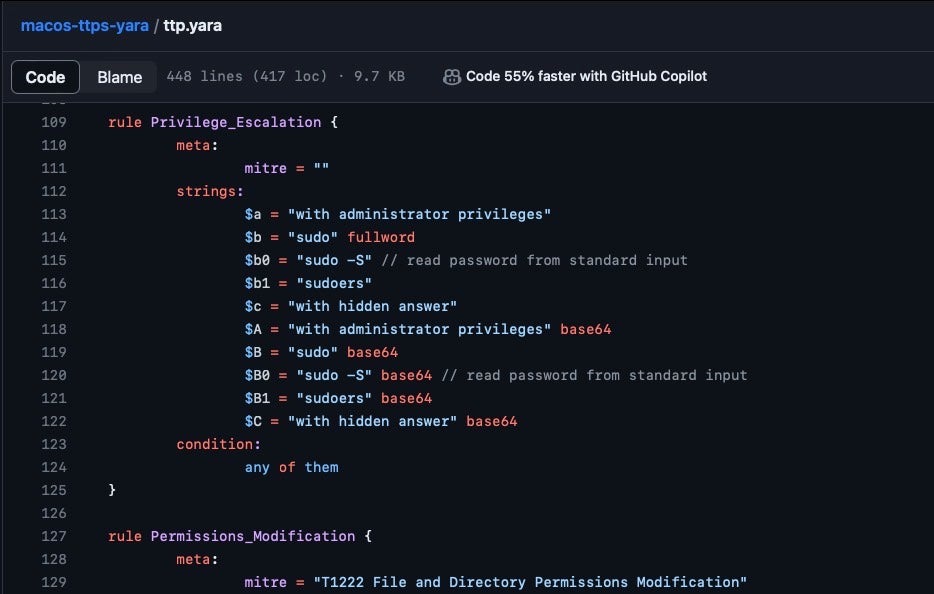

Threat hunters are most familiar with using YARA to determine if a sample file contains strings or bytes similar to other known malware families, but we can also use the same technique to find interesting code typical of malware TTPs. Take the following YARA rule, for example:

This rule returns a match if the binary contains certain strings related to disabling or modifying tools or other processes on a device, a typical anti-analysis and evasion technique. We can create a list of rules with various TTP indicators to help us to statically determine what capabilities a file has that may be related to malware behavior. Here is another example of a rule to indicate a binary that contains code related to system discovery.

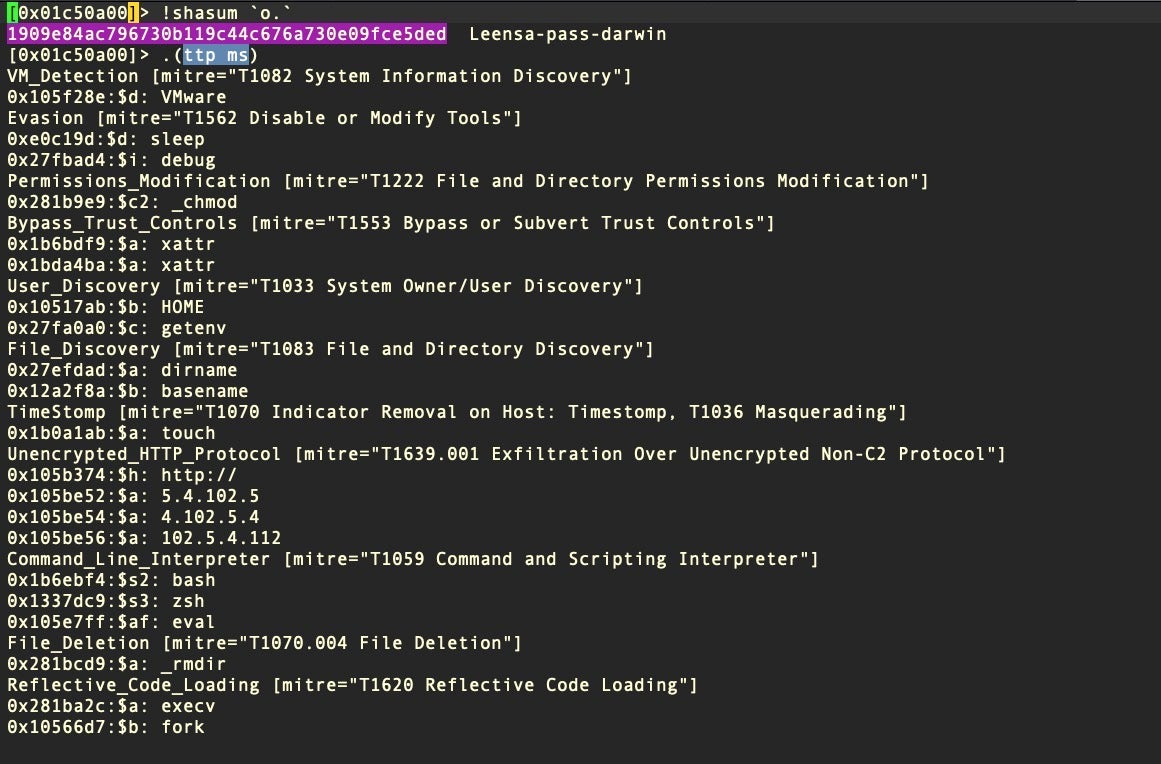

We can run our YARA rule set on a given binary from within a radare2 session and, by leveraging YARA’s -m and -s switches, obtain a list of possible TTPs and their offsets for further investigation.

In this example we create a radare2 alias to run our YARA TTP ruleset over the file. The alias is equivalent to the command:

yara -ms ttp.yara

In radare2, the alias can be defined locally within the current r2 session or more usefully as a global alias in the .radare2rc config file as:

(ttp x; !yara -$0w <path to>/ttp.yara `o.`)

We provide a starter YARA rule set here that other macOS malware analysts can use as a base from which to develop their own more comprehensive ttp.yara file.

Conclusion

Massive binaries are becoming increasingly common on the macOS platform and defenders need strategies for dealing with them. Malware authors have embraced the idea of distributing huge binaries in part as a tactic for defense evasion and anti-analysis and in part as a result of turning to cross-platform languages that pack a runtime, library and other dependencies in the final payload.

Organizations can detect large malicious binaries by turning to solutions that include behavioral detection and do not rely solely on file scanning. Analysts can implement techniques such as those discussed above to help them triage massive macOS malware samples faster and more efficiently.