By Antonio Pirozzi, Antonis Terefos and Idan Weizman

Executive Summary

- Since OFAC sanctions in 2020, the global intelligence community has been split into different camps as to how Evil Corp is operating.

- SentinelLabs assesses with high confidence that WastedLocker, Hades, Phoenix Locker, PayloadBIN belong to the same cluster. There are strong overlaps in terms of code similarities, packers, TTPs and configurations.

- SentinelLabs assesses with high confidence that the Macaw ransomware variant is derived from the same codebase as Hades.

- Our analysis indicates that Evil Corp became a customer of the CryptOne packer-as-a-service from March 2020. We created a static unpacker, de-CryptOne for CryptOne and identified different versions of this cryptor which have never previously been reported.

Introduction

Evil Corp (EC) is an advanced cybercrime operations cluster originating from Russia that has been active since 2007. The UK National Crime Agency called it “the world’s most harmful cyber crime group.” In December 2019, the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) issued a sanction against 17 individuals and seven entities related to EC cyber operations for causing financial losses of more than 100 million dollars with Dridex.

After the indictments, the global intelligence community was split into different camps as to how Evil Corp was operating. Some assessed that there was a voluntary transition of EC operations to another ‘trusted’ partner while the core group remained the controller of operations. Some had theories that Evil Corp had stopped operating and that another advanced actor operated Hades, trying to mimic the same modus operandi as Evil Corp to mislead attribution. Others claimed possible attribution to the HAFNIUM activity cluster.

SentinelLabs has conducted an in-depth review and technical analysis of Evil Corp activity, malware and TTPs. Our full report has a number of important findings for the research community. We relied heavily on our analysis of a crypter tool dubbed “CryptOne”, which supports our wider clustering of Evil Corp activity. Our research also argues that the original operators continue to be active despite the sanctions, continuously changing their TTPs in order to stay under the radar.

In this post, we summarize some key observations from our technical analysis on the evolution of Evil Corp from Dridex through to Macaw Locker and, for the first time, publicly describe CryptOne and the role it plays in Evil Corp malware development. For the full technical analysis, comprehensive IOCs and YARA hunting rules, please see the full report.

Overview of Recent Evil Corp Activity

After the OFAC indictment, we witnessed a change in Evil Corp TTPs: from 2020, they started to frequently change their payload signatures, using different exploitation tools and methods of initial access. They switched from Dridex to the SocGholish framework to confuse attribution and distance themselves from both Dridex and Bitpaymer, which fell within the scope of the sanctions. During this period, they started relying more heavily on Cobalt Strike to gain an initial foothold and perform lateral movement, rather than PowerShell Empire.

In May 2020, a new ransomware variant appeared in the wild dubbed WastedLocker. WastedLocker (S0612) employed techniques to obfuscate its code and perform tasks similar to those already seen in BitPaymer and Dridex. Those similarities allowed the threat intelligence community to identify the connections between the malware families.

In December 2020, a new ransomware variant named Hades was first seen in the wild and publicly reported. Hades is a 64-bit compiled version of WastedLocker that displays important code and functionality overlaps. A few months later, in March 2021, a new variant Phoenix Locker appeared in the wild. Our analysis suggests this is a rebranded version of Hades with little to no changes. Later, a new variant named PayloadBIN appeared in the wild, a continuation from Phoenix Locker.

A Unique Cluster: BitPaymer, WastedLocker, Hades, Phoenix Locker, PayloadBIN

From our analysis, we discovered evidence of code overlaps, as well as shared configurations, packers and TTPs leading us to assess with high confidence that Bitpaymer, WastedLocker, Hades, PhoenixLocker and PayloadBIN share a common codebase. Our full report goes into the evidence in fine detail. The following section presents a brief summary.

From BitPaymer to WastedLocker

Previous research shows a sort of knowledge reuse between BitPaymer and WastedLocker. SentinelLabs analysis shows that Hades and WastedLocker share the same codebase.

Among other similarities, detailed in the full report, we observe that the RSA functions – responsible for asymmetrically encrypting the keys which were used in the AES phase to encrypt files – are identical in both ransomware variants, hinting that the same utility library was used.

From WastedLocker to Hades

Previous research assessed the main similarities and differences between the two ransomware families. SentinelLabs analysis shows that Hades and WestedLocker share the same codebase.

Again we see the same RSA functions in both families. Both also implement file and directory enumeration logic identically. Comparing the logic and the Control Flow Graph of both routines, we conclude that both ransomware use the same code for file and directory enumeration. We also found similarities between the functions responsible for drive enumeration.

From Hades to Phoenix Locker

In the samples we analyzed, we discovered that Phoenix Locker was a reused and newly-packed Hades payload. Hades and Phoenix samples were compiled at the same time. We confirmed that they reused a ‘clean’ Hades version each time, statically introducing junk code with the help of a script in order to alter the signature. The compiler and linker versions are also the same. This technique of payload reuse was also seen in BitPaymer in order to make the ransomware polymorphic and more evasive.

From Phoenix Locker to PayloadBIN

We observed that the majority of PayloadBIN functions overlap with PhoenixLocker. File enumerating functions are practically identical.

We conducted further similarity analysis by analyzing the TTPs of the different variants. We did this by extracting the main command lines from all the ransomwares and comparing them. We distinguished two distinct clusters.

From Hades onwards, we found a unique self-delete implementation including the waitfor command.

cmd /c waitfor /t 10 pause /d y & attrib -h "C:\Users\Admin\AppData\Roaming\CenterLibrary\Tip" & del "C:\Users\Admin\AppData\Roaming\CenterLibrary\Tip" & rd "C:\Users\Admin\AppData\Roaming\CenterLibrary\"

This command is not present in WastedLocker, where the choice command is used instead:

cmd /c choice /t 10 /d y & attrib -h "C:\Users\Admin\AppData\Roaming\Wmi" & del "C:\Users\Admin\AppData\Roaming\Wmi"

Whilst syntax difference may seem like a significant difference, these two implementations are very similar: the logic is the same, only the signature changes.

All ransomwares have the same implementation of Shadows copy deletion:

C:\Windows\system32\vssadmin.exe Delete Shadows /All /Quiet

The evidence of this code reuse supports the assessment that it is almost certain these ransomware families are related to the same ‘factory’.

Analysis of the Cypherpunk Variant

A new, possibly experimental, variant dubbed “Cypherpunk” – first reported in June 2021- was analyzed and linked to the same lineage.

C:\Users\Lucas\Documents\OneNote Notebooks\Personal\General.one.cypherpunk C:\Users\Lucas\Documents\OneNote Notebooks\Personal\CONTACT-TO-DECRYPT.txt C:\Users\Lucas\Documents\awards.xls.cypherpunk C:\Users\Lucas\Desktop\ZoneMap.dwf.cypherpunk C:\Users\Administrator\Searches\Everywhere.search-ms.cypherpunk C:\Users\Lucas\Desktop\th (2).jpg.cypherpunk C:\Users\Lucas\Documents\pexels-photo-46710.jpeg.cypherpunk C:\Users\Lucas\Desktop\ppt_ch10.ppt.cypherpunk C:\Users\Lucas\Desktop\WEF_Future_of_Jobs.pdf.cypherpunk

Code similarity analysis shows that the Cypherpunk version (SHA1 e8d485259e64fd375e03844c03775eda40862e1c) is the same as the previous PayloadBIN variant. It was compiled on 2021-04-01 17:15:24, 20 days after the PayLoadBIN sample. It is possible that this is another attempt at rebranding. Although this variant was reported, it was improperly flagged as Hades.

SentinelLabs assesses this new finding is likely an indication that Evil Corp is still working on updating their tradecraft in order to change their signature and stay under the radar.

Evil Corp Pivots to Macaw Locker Ransomware

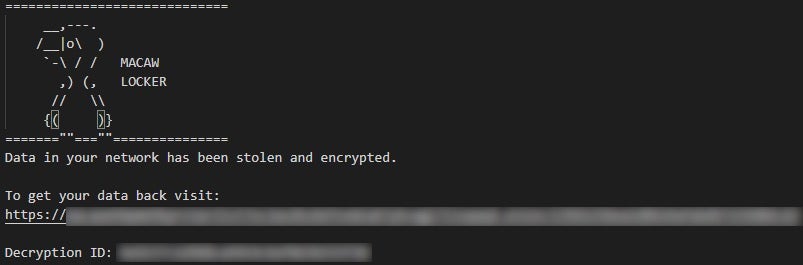

In October 2021, a new ransomware variant named ‘Macaw Locker’ appeared in the wild, in an attack that began on October 10th against Olympus. A few days later Sinclair Broadcast Group was also attacked, causing widespread disruption. Some researchers claimed a possible connection with WastedLocker, but to date no further details have emerged.

The ransomware presents anti-analysis features like API hashing and indirect API calls with the intention of evading analysis. One aspect that immediately sets Macaw apart is that it requires a custom token, provided from the command line, which appears to be specific to each victim; without it, the ransomware won’t execute.

macaw_sample.exe -k

The use of a custom token is also seen in Egregor and BlackCat ransomware families, and is a technique used to aid anti-analysis (T1497.002).

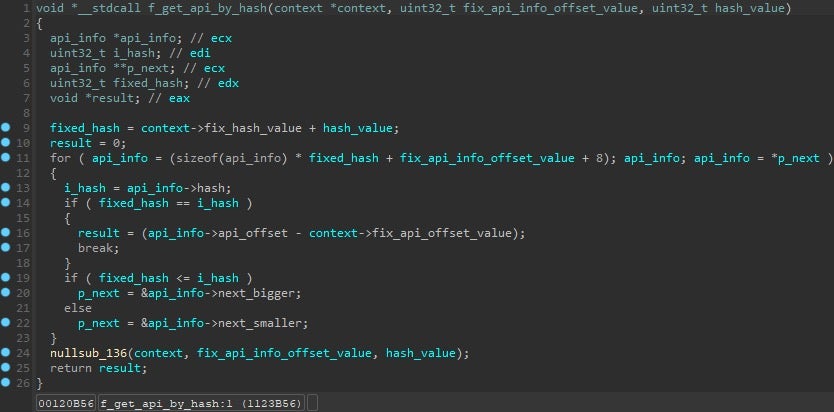

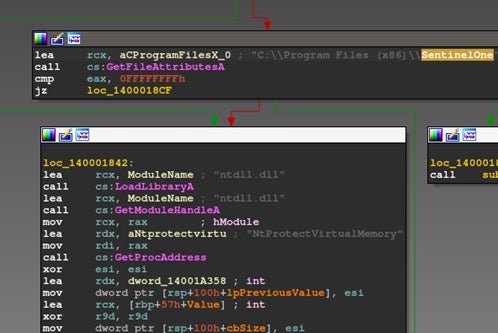

Another new addition to Macaw is a special function that acquires the imports for APIs at runtime, instead of when the executable is started via the PE import section. Below, we can see the function that is used before each API call to get its address prior to the call itself.

The function gets a 32-bit value that uniquely represents the required API and searches for it through a data structure created beforehand. The data structure can be described as an array with small binary search trees in each of its entries.

We assessed the similarity of two core functions between Hades and Macaw. In both strains, the implementation is the same. The only minor differences are from the imports fetched at runtime.

CryptOne: One Packer To Rule Them All

CryptOne (also known as HellowinPacker) was a special packer used by Evil Corp up until mid-2021.

CryptOne appears to have first been noticed in 2015. Early versions were used by an assortment of different malware families such as NetWalker, Gozi, Dridex, Hancitor and Zloader. In 2019, Bromium analyzed and reported it as in use by Emotet. In June 2020, NCC Group reported that CryptOne was used to pack WastedLocker. In 2021, researchers observed CryptOne being advertised as a Packer-as-a-Service on various crime-oriented forums.

CryptOne has the following characteristics and features:

- Sandbox evasion with

getInputState()orGetKeyState()API; - Anti-emulation with

UCOMIEnumConnectionsand theIActiveScriptParseProcedure32interface; - Code-flow obfuscation;

We created a static unpacker, de-CryptOne, which unpacks both x86 and x64 samples. It outputs two files:

- the shellcode responsible for unpacking

- the unpacked sample.

We collected CryptOne packed samples, and with the use of the above tool, unpacked and categorized them at scale.

Unpacking CryptOne

CryptOne unpacking method consists of two stages:

- Decrypts and executes embedded shellcode.

- Shellcode decrypts and executes embedded executables.

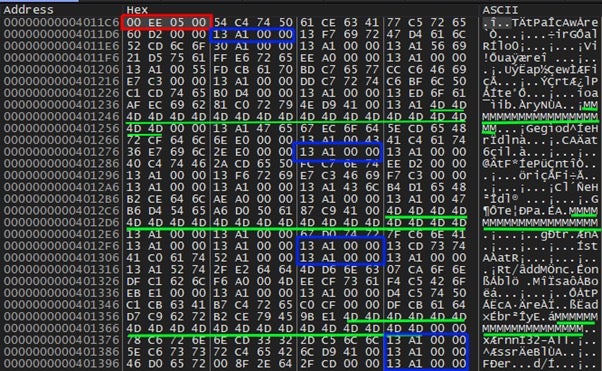

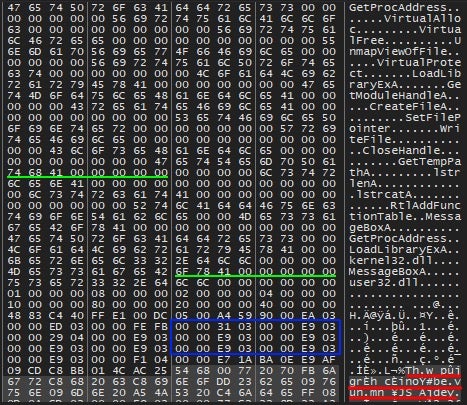

CryptOne gets chunks of the encrypted data, which are separated by junk.

Example Memory Dump:

- 0x5EE00, Encrypted size

- 0x4011CA, Address of encrypted data

- 0x4D/”M”, Junk data

- 0x14, Junk size

- 0x7A, Chunk Size

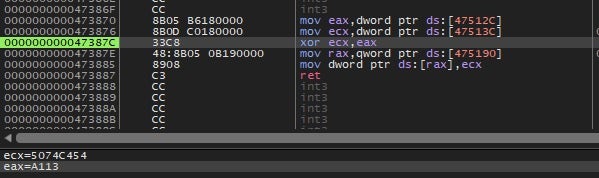

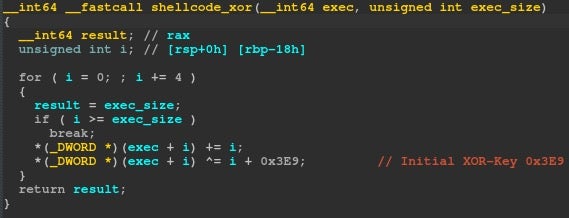

After removal of the junk data, the decryption starts with a simple XOR-Key which increases by 0x4 in each round. The initial XOR-Key is 0xA113.

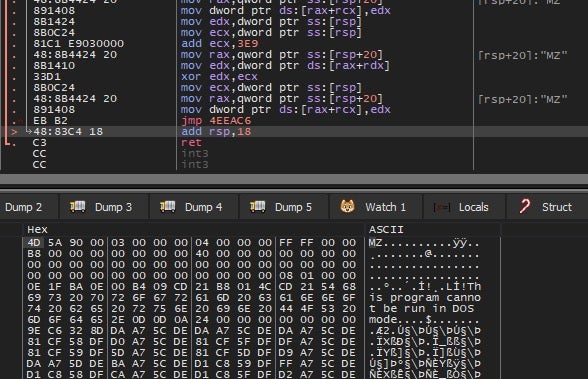

Once the shellcode is decrypted, we can partially observe the string “This program cannot be run in DOS mode” where this data contains an executable which requires a second decryption.

Similar to previous decryption, this time the shellcode decrypts the embedded binary.

The shellcode allocates and copies the encrypted executable and starts the decryption loop; once it finishes, it jumps to the EntryPoint and executes the unpacked sample.

At this stage we can observe strings related to the unpacked sample.

A Unique Factory

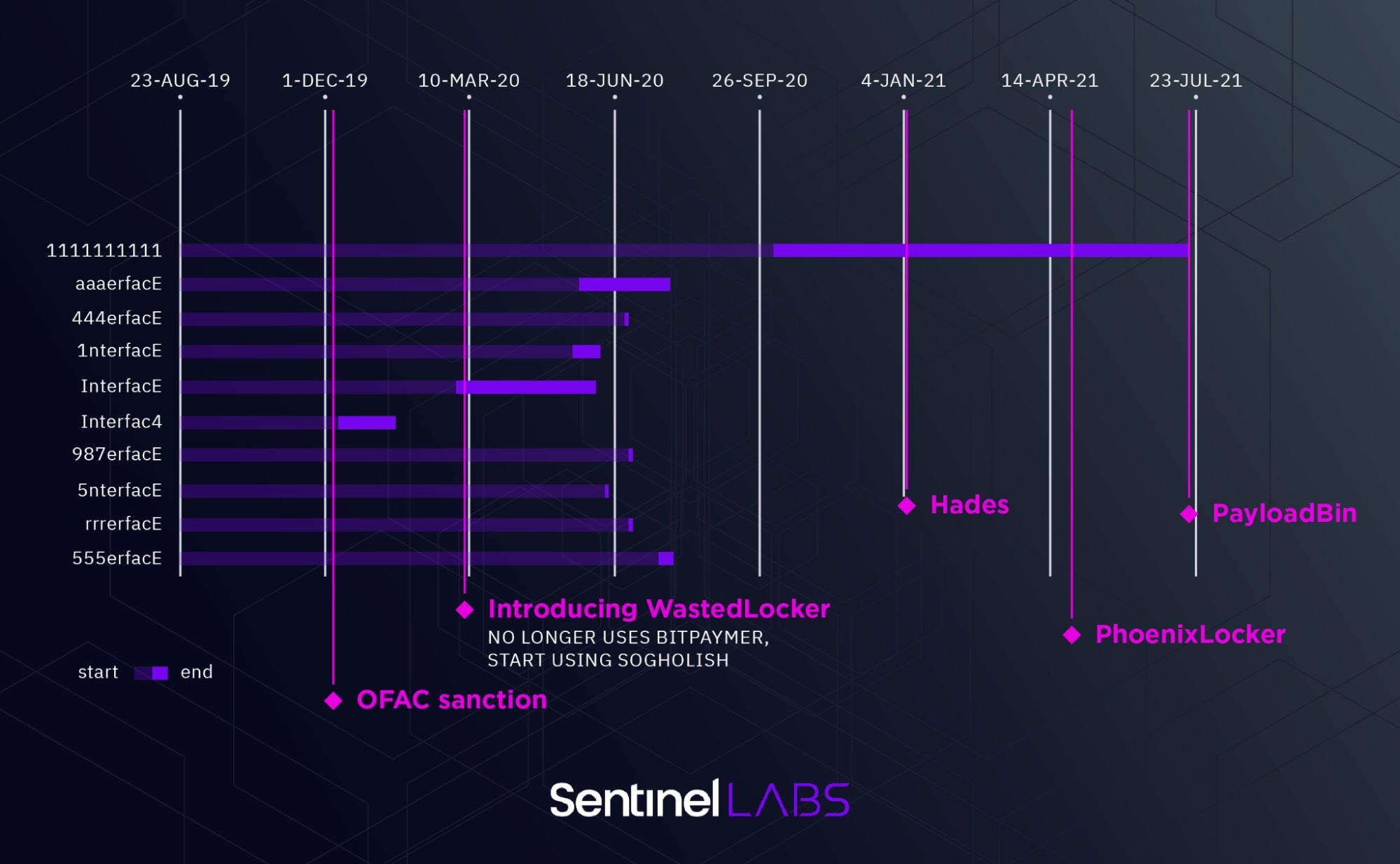

Hunting for CryptOne led us to identify different implementations of the stub, some of which have never been reported previously. Each version is identified by a certain signature, listed below:

- 111111111\\{aa5b6a80-b834-11d0-932f-00a0c90dcaa9}

- 1nterfacE\\{b196b287-bab4-101a-b69c-00aa00341d07}

- 444erfacE\\{b196b287-bab4-101a-b69c-00aa00341d07}

- 555erfacE\\{b196b287-bab4-101a-b69c-00aa00341d07}

- 5nterfacE\\{b196b287-bab4-101a-b69c-00aa00341d07}

- 987erfacE\\{b196b287-bab4-101a-b69c-00aa00341d07}

- Interfac4\\{b196b287-bab4-101a-b69c-00aa00341d07}

- InterfacE\\{b196b287-bab4-101a-b69c-00aa00341d07}

- aaaerfacE\\{b196b287-bab4-101a-b69c-00aa00341d07}

- interfacE\\{b196b287-bab4-101a-b69c-00aa00341d07}

- rrrerfacE\\{b196b287-bab4-101a-b69c-00aa00341d07}

The first part of the string is composed of a custom string (111111111, 1nterfacE, 444erfacE,…) which is replaced at runtime by the ‘interface’ keyword, creating the following registry key:

HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT\interface\{b196b287-bab4-101a-b69c-00aa00341d07}

The registry keys are related to the UCOMIEnumConnections and IActiveScriptParseProcedure32 interfaces respectively.

Once executed, the cryptor checks for the presence of those keys before loading the next stage payload. If it does not find the keys, then the malware goes into an endless loop without doing anything as an anti-emulation technique. This works because some emulators do not implement the full Windows registry.

In reviewing two different versions of CryptOne:

aaerfacE\\{b196b287-bab4-101a-b69c-00aa00341d07}

111111111\\{aa5b6a80-b834-11d0-932f-00a0c90dcaa9}

we noticed that in order to update the signature, the actor needs to re-compile the cryptor as the cryptor implementation changes.

CryptOne Timeline

Our analysis shows that it is likely Evil Corp started being a customer of the CryptOne service from March 2020. From March to May 2020 we found WastedLocker, gozi_rm3 (version:3.00 build:854) and Dridex (10121) samples were all packed and compiled in the same timeframe using the same CryptOne stub signature(InterfacE).

For a limited period of time between May 2020 and August 2020, we observed different versions of CryptOne overlaps.

It seems that from a specific point in time, around September 2020, Hades, PhoenixLocker and PayloadBIN started adopting a specific CryptOne stub identified by the signature:

111111111\\{aa5b6a80-b834-11d0-932f-00a0c90dcaa9}

From December 2020, the CryptOne version ‘111111111’ appeared in the wild without any overlap.

Conclusion

Clustering Evil Corp activity is demonstrably difficult considering that the group has changed TTPs several times in order to bypass sanctions and stay under the radar. This is in addition to the overall trend of actors receding back into secrecy. In this research, we connect the dots in the Evil Corp ecosystem, cluster Evil Corp malware, document the group’s activities and provide insight into their TTPs.

SentinelLabs assesses with high confidence that WastedLocker, Hades, PhoenixLocker, Macaw Locker and PayloadBIN belong to the same cluster. Our assessment is based on code similarity and reuse, timeline consistency and nearly identical TTPs across the ransomware families indicating there is a consistent modus operandi for the cluster. In addition, we assess that there is a likely evolutionary link between WastedLocker and BitPaymer, and suggest that it can be attributed to the same Evil Corp activity cluster.

We fully expect that Evil Corp will continue to evolve and target organizations. In addition, we assess it is likely they will also continue to advance their tradecraft, finding new methods of evading detection and misleading attribution. SentinelLabs will continue tracking this activity cluster to provide insight into its evolution.

In-depth technical analysis, Indicators of Compromise and further technical references are available in the full report.