By Yi-Jhen Hsieh & Joey Chen

Executive Summary

- ShadowPad is a privately sold modular malware platform –rather than an open attack framework– with plugins sold separately.

- ShadowPad is still regularly updated with more advanced anti-detection and persistence techniques.

- It’s used by at least four clusters of espionage activity. ShadowPad was the primary backdoor for espionage operations in multiple campaigns, including the CCleaner, NetSarang, and ASUS supply-chain attacks.

- The adoption of ShadowPad significantly reduces the costs of development and maintenance for threat actors. We observed that some threat groups stopped developing their own backdoors after they gained access to ShadowPad.

- As a byproduct of that shared tooling, any claim on attribution needs to be reviewed in a cautious way when a shared backdoor like ShadowPad is involved.

- Instead of focusing on specific threat groups, we discuss local personas possibly involved in the development of ShadowPad as an iterative successor to PlugX.

Overview

ShadowPad emerged in 2015 as the successor to PlugX. However, it was not until several infamous supply-chain incidents occurred – CCleaner, NetSarang and ShadowHammer – that it started to receive widespread attention in the public domain. Unlike the publicly-sold PlugX, ShadowPad is privately shared among a limited set of users. Whilst collecting IoCs and connecting the dots, we asked ourselves: What threat actors are using ShadowPad in their operations? And ultimately, how does the emergence of ShadowPad impact the wider threat landscape from Chinese espionage actors?

To answer those questions, we conducted a comprehensive study on the origin, usage and ecosystem of ShadowPad. The full report provides:

- a detailed overview of ShadowPad, including its history, technical details, and our assessment of its business model and ecosystem

- a detailed description of four activity clusters where ShadowPad has been used

- a discussion of how ShadowPad’s emergence changes the attacking strategies of some China-based threat actors

- how ShadowPad affects the threat landscape of Chinese espionage attacks

In this blog post, we provide an abridged version of some of our key findings and discussions. Please see the full report for an extended discussion, full Indicators of Compromise and other technical indicators.

Technical Analysis

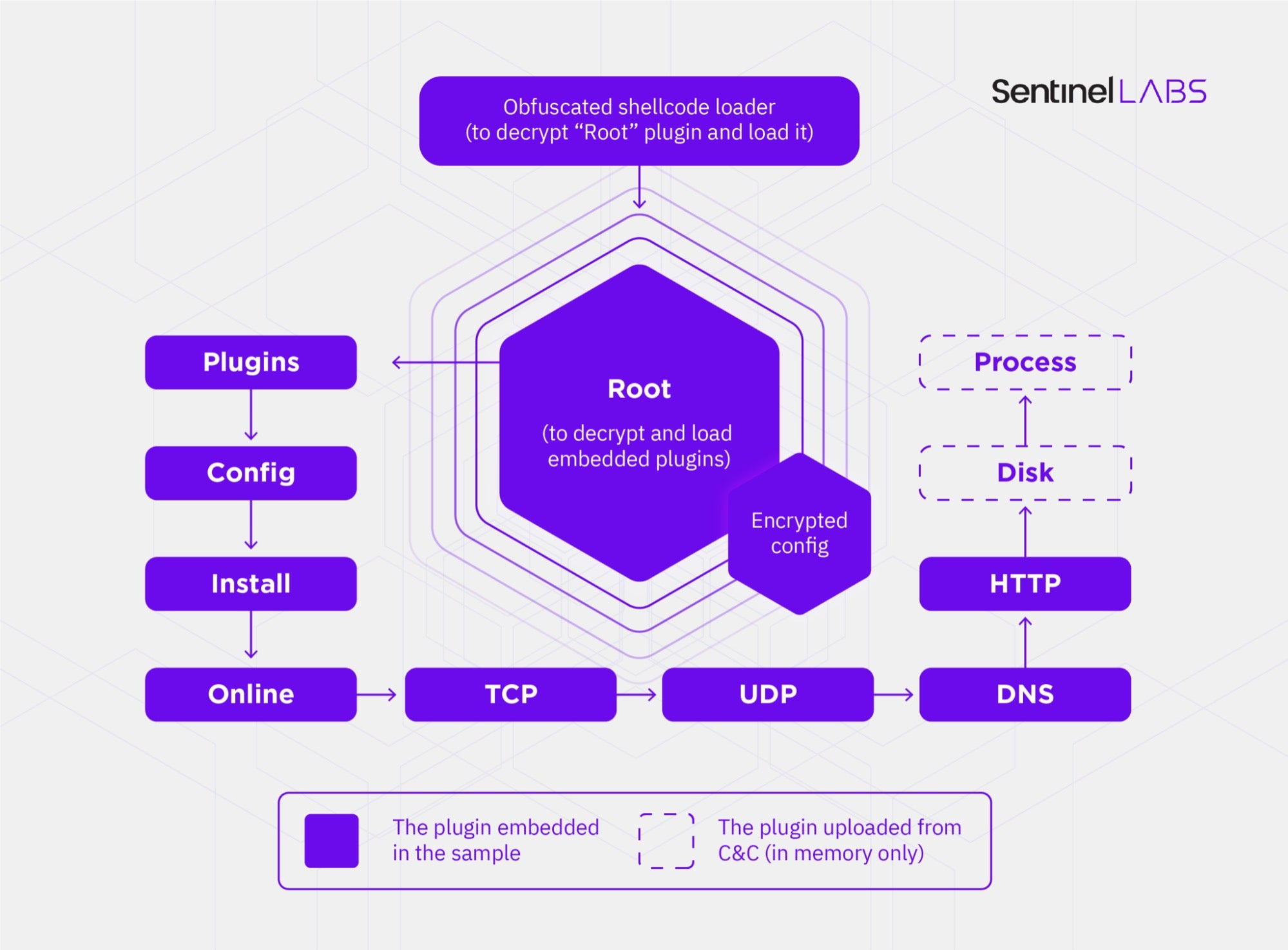

ShadowPad is a modular backdoor in shellcode format. On execution, a layer of an obfuscated shellcode loader is responsible for decrypting and loading a Root plugin. While the sequence of operation in the Root plugin decrypts, it loads other plugins embedded in the shellcode into memory. The plugins are kept and referenced through a linked list:

struct plugin_node {

plugin_node* previous_node;

plugin_node* next_node;

DWORD referenced_count;

DWORD plugin_timestamp;

DWORD plugin_id;

DWORD field_0;

DWORD field_1;

DWORD field_2;

DWORD field_3;

DWORD plugin_size;

LPVOID plugin_base_addr;

LPVOID plugin_export_function_table_addr;

}

Along with the plugins embedded in the sample, additional plugins are allowed to be remotely uploaded from the C&C server, which allows users to dynamically add functionalities not included by default.

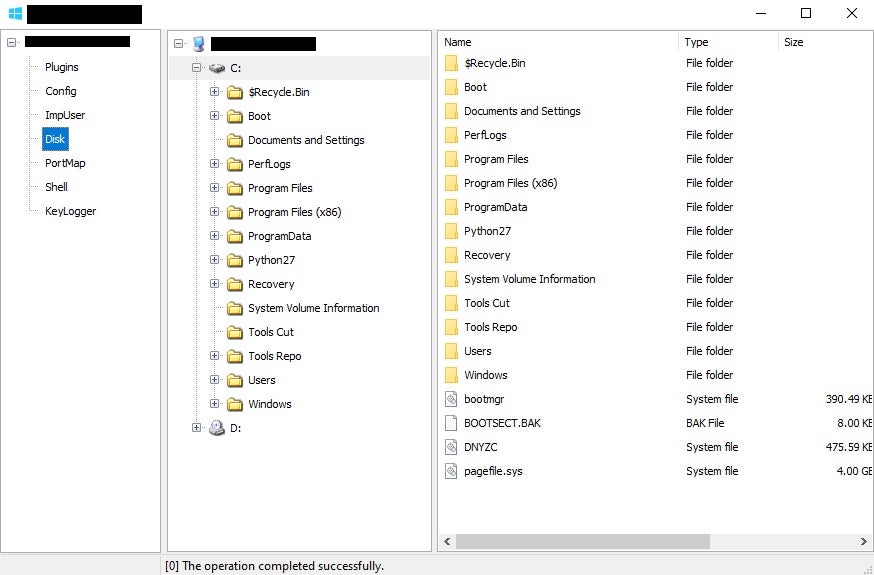

As luck would have it, the ShadowPad controller (version 1.0, 2015) was accidentally discovered during private research. All of the stakeholders involved agreed to our releasing screenshots but not the details of the actual file, so we are unable to provide hashes for this component at present.

Analysis of the controller allowed us to obtain a clear picture of how the builder generates the shellcodes, how the users manage the infected hosts, and the kinds of functions available on the controller.

Privately Shared Attack Framework or Privately Sold Modular Malware?

An intriguing question to address is whether ShadowPad is a privately shared attack framework or a privately developed modular malware platform for sale to specific groups. Its design allows the users to remotely deploy new plugins to a backdoor. In theory, anyone capable of producing a plugin that is encrypted and compressed in the correct format can add new functionalities to the backdoor freely.

However, the control interfaces of the plugins are hardcoded in the “Manager” page of the ShadowPad controller, and the controller itself does not include a feature to add a new control interface.

In other words, it is unlikely that ShadowPad was created as a collaborative attacking framework. Only the plugins produced by the original developer could be included and used through the ShadowPad controller.

On the other hand, even if the control interface of a plugin is listed in the menu, not every available plugin is embedded in the ShadowPad samples built by the controller by default. There is no configuration in the builder to allow the user to choose which plugins are compiled into the generated sample, so this setting can only be managed by the developer of the controller.

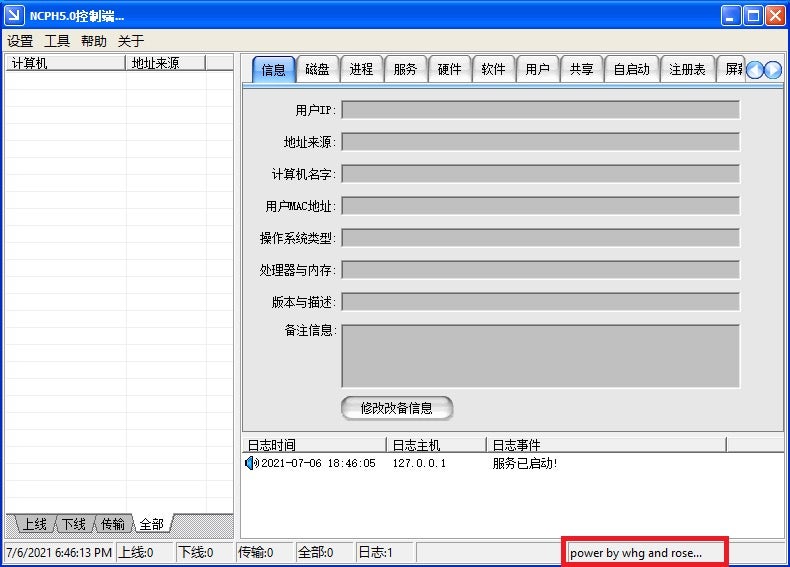

If ShadowPad was not originally designed as an open framework, the following question is whether it is freely shared with or sold to its users. The possible author ‘whg’ – and one of his close affiliates, Rose – have been monetizing their malware development and hacking skills since the early 2000s. Both individuals sold self-developed malware, and Rose offered services such as software cracking, penetration testing and DDoS attacks. If ShadowPad was developed by them or their close affiliates, it is more likely to be sold to – rather than freely shared with – other users under this context.

Selling the Plugins Separately Rather than Giving a Full Bundle by Default

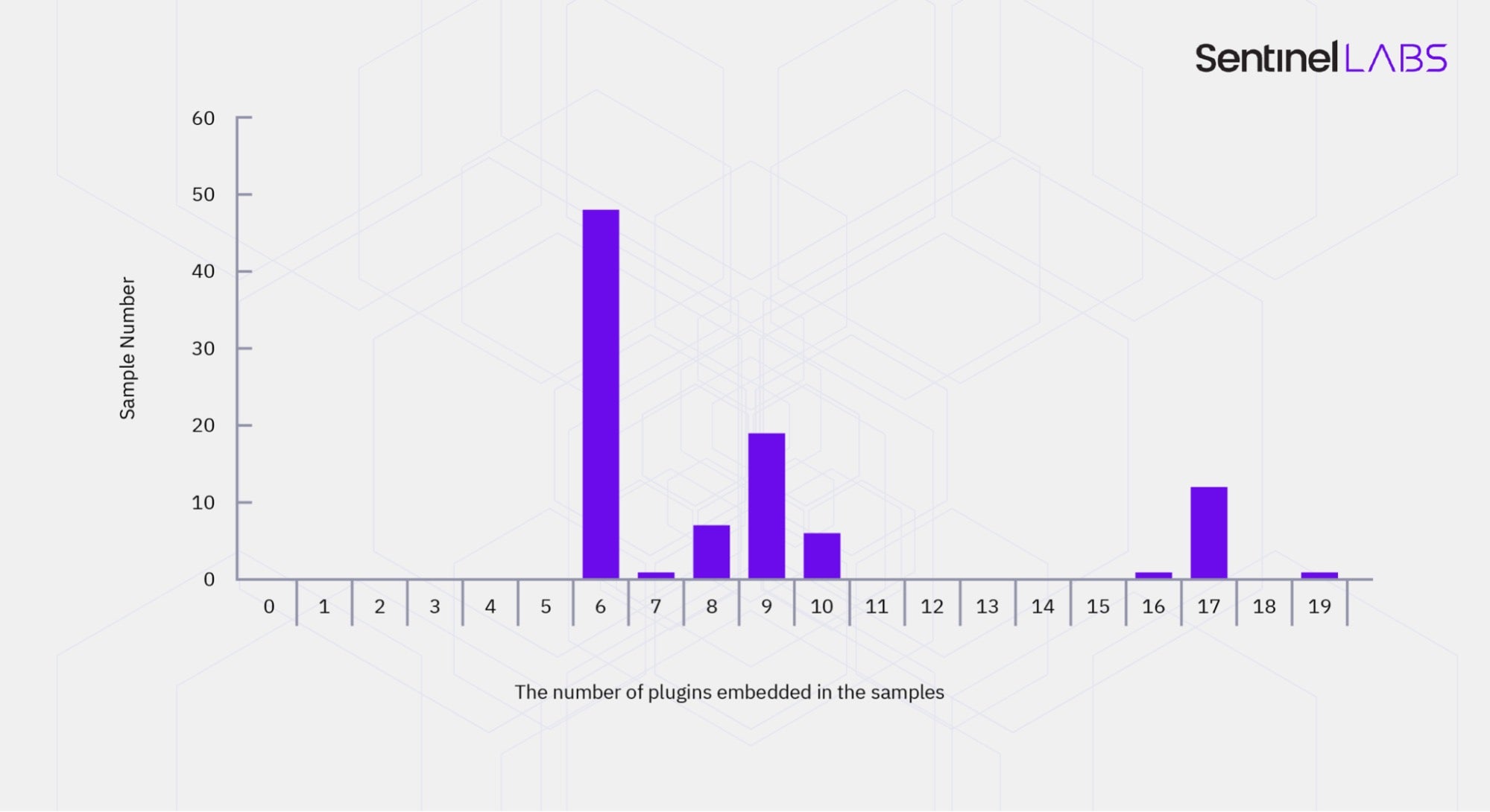

The available functionalities to ShadowPad users are highly controlled by the seller of ShadowPad. Looking deeply into the plugin numbers and the distribution of different plugins embedded in around a hundred samples, we assessed that the seller is likely selling each plugin separately instead of offering a full bundle with all of the currently available plugins.

The image above groups the samples by the number of the plugins embedded in them. Most of the samples contain less than nine plugins with the following plugins embedded: Root, Plugins, Config, Install, Online, TCP, HTTP, UDP and DNS. This set of plugins can only support the installation of backdoors and communications with C&C servers, without providing further functionality.

What Threat Actors Are Using Shadowpad?

ShadowPad is sold privately to a limited set of customers. SentinelOne has identified at least five activity clusters of ShadowPad users since 2017:

- APT41

- Tick & Tonto Team

- Operation Redbonus

- Operation Redkanku

- Fishmonger

In the full report, we discuss each in turn. Here, we will limit our observations to the most interesting points related to APT41.

APT41 is the accepted naming convention for the activities conducted by two spinoffs of what was once referred to as ‘Winnti’, sub-groups – BARIUM (Tan Dailin aka Rose and Zhang Haoran) and LEAD (Chengdu 404 Network Technology Co., Ltd).

All of the individuals are based in Chengdu, Sichuan. Rose (aka “凋凌玫瑰”), Zhang Haoran, and Jiang Lizhi (aka “BlackFox”, one of the persons behind Chengdu 404) were coworkers between 2011 and 2017, while Rose and BlackFox knew each other since at least 2006.

Rose started his active collaboration on malware development with whg, the author of PlugX, when he was a member of the hacking group NCPH back in 2005. They developed “NCPH Remote Control Software” together until 2007. The executable of the controller was freely shared on NCPH websites, but they also declared that the source code was for sale.

BARIUM (Rose and Zhang Haoran) were one of the earliest threat groups with access to ShadowPad. Aside from some smaller-scale attacks against the gaming industry, they were accountable for several supply chain attacks from 2017 to 2018. Some of their victims included NetSarang, ASUS, and allegedly, CCleaner.

Another subgroup, LEAD, also used ShadowPad along with other backdoors to attack victims for both financial and espionage purposes. They were reported to attack electronic providers and consumers, universities, telecommunication, NGO and foreign governments.

Considering the long-term affiliation relationship between Rose and whg, we suspect that Rose likely had high privilege access to – or was a co-developer of – ShadowPad, and other close affiliates in Chengdu were likely sharing resources. This could also explain why BARIUM was able to utilize a special version of ShadowPad in some of their attacks.

Conclusion

The emergence of ShadowPad, a privately sold, well-developed and functional backdoor, offers threat actors a good opportunity to move away from self-developed backdoors. While it is well-designed and highly likely to be produced by an experienced malware developer, both its functionalities and its anti-forensics capabilities are under active development. For these threat actors, using ShadowPad as the primary backdoor significantly reduces the costs of development.

For security researchers and analysts tracking China-based threat actors, the adoption of the “sold – or cracked – commercial backdoor” raises difficulties in ascertaining which threat actor they are investigating. More systematic ways – for instance, analysis on the relationship between indicators, long-term monitoring on the activities and campaigns – need to be developed in order to carry out analytically-sound attribution. Any claim made publicly on the attribution of ShadowPad users requires careful validation and strong evidentiary support so that it can help the community’s effort in identifying Chinese espionage.

Read the full report for an extended discussion, full Indicators of Compromise and other technical indicators.