Ransomware is one of cybercrime’s most fearsome weapons. With some estimates claiming it could cause losses of $7.5 billion in the US and $2.3 Billion for Canadian companies, there’s no doubt its financial impact is felt throughout the world, even if those figures may not be quite on the mark.

But in addition to the direct and indirect financial damage, ransomware differs from other forms of cybercrime by employing deep psychological mechanisms. In contrast to almost any other type of malware, ransomware doesn’t conceal its activity; it announces itself to the victim and coerces the target toward action (paying the ransom). Precisely how ransomware leverages the victim’s fears, beliefs, motives and values has evolved over time, both in response to attackers learning from their own mistakes – resulting in victims not paying – and the behavior of victims and the security industry, such as getting better at off-site backups and creating decryptors. In this post, we take a look at how the psychological mechanisms used by ransomware operators have evolved over time in an attempt to maximize the chances of a payout.

What Do Ransomware Attackers Need?

The basic functionality of ransomware involves initial infection, rapid encryption and victim notification, where the victim is informed that they have lost access to their data and must make payment for its release. On a psychological level, what criminals need to ensure is:

A. That they grab the attention of the victim (ransomware that goes unnoticed is useless).

B. Apply leverage on the victims; they must be persuaded that payment is their only viable option.

C. Create a sense of urgency: in order to maximize profitability, speed is of the essence (it allows greater throughput and higher returns before the malware is neutralized by security vendors).

Ever since the first ransomware was introduced in 1989, the ransom demand methods have evolved through continual “trial and error” in an ongoing attempt to maximize the yield and reduce the risk involved.

Early Ransomware: Your Check is in the Post!

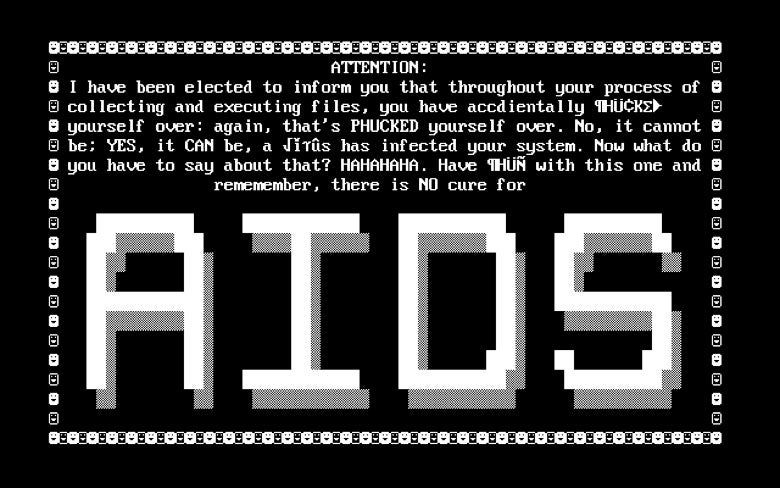

The first ever ransomware was created in 1989 by the biologist Joseph L. Popp. He distributed the malware in a rather old-fashioned way, by mailing (not emailing) 20,000 infected diskettes labeled “AIDS Information: Introductory Diskettes” to attendees of the World Health Organization’s international AIDS conference in Stockholm. Once executed, the malware hid file directories, encrypted file names and demanded victims send $189 to a PO Box in Panama if they wanted their data decrypted.

Popp made little if no money as it turned out. Decryptors were soon created that could reverse the damage done, but it did strike terror into its victims. There were reports that some medical institutions threw away up to 10 years of research after being hit by the ransomware.

Popp used several kinds of notifications to the victim; like many others that would follow in his footsteps, he indulged in mocking and scaring the victim:

Hurry, Hurry! Buy Now, While Stocks Last!

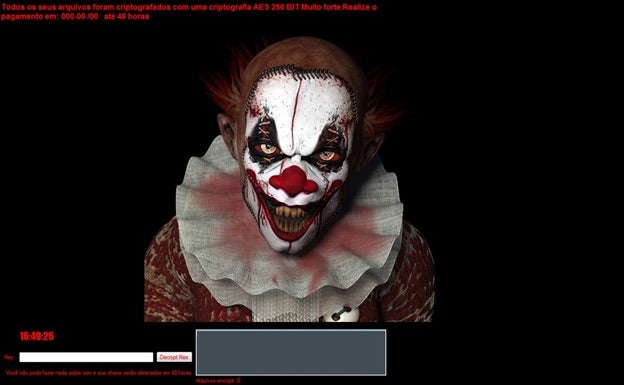

Many years passed before ransomware would hit the big time and started to employ other psychological mechanisms. One of the first to be introduced was a timer counting down to a point in the near future (say, 48 hours from infection) after which the files would be deleted and be totally unrecoverable, regardless of whether the victim subsequently wanted to pay.

This mechanism is well known from the marketing world, and is used to create a sense of urgency. However, many ransomware victims were unable to pay within the given time, or didn’t understand what they had to do, or wasted all the countdown period looking for help, such that many of them missed the deadline, forcing attackers to carry out their threat and delete the encryption keys, leaving the files locked forever.

While the countdown method helped to enhance the evil, relentless reputation of this kind of attack, it had a downside for the criminals: it wasn’t very effective in terms of maximizing returns as many victims would have paid eventually, but the countdown method made it impossible to collect the ransom. As a result, eventually ransomware perpetrators were forced to adapt the method. Newer forms of ransomware now often try to incentivise the victim by offering a lower price the faster they respond. “The faster you get in contact – the lower price you can expect”.

Shock and Awe: Alarming Sounds and Images

Pushing people to action then shifted to using visual and auditory scare tactics. The ransom note became more sinister and incorporated scary visuals and alarming sounds, intended to make it impossible to ignore.

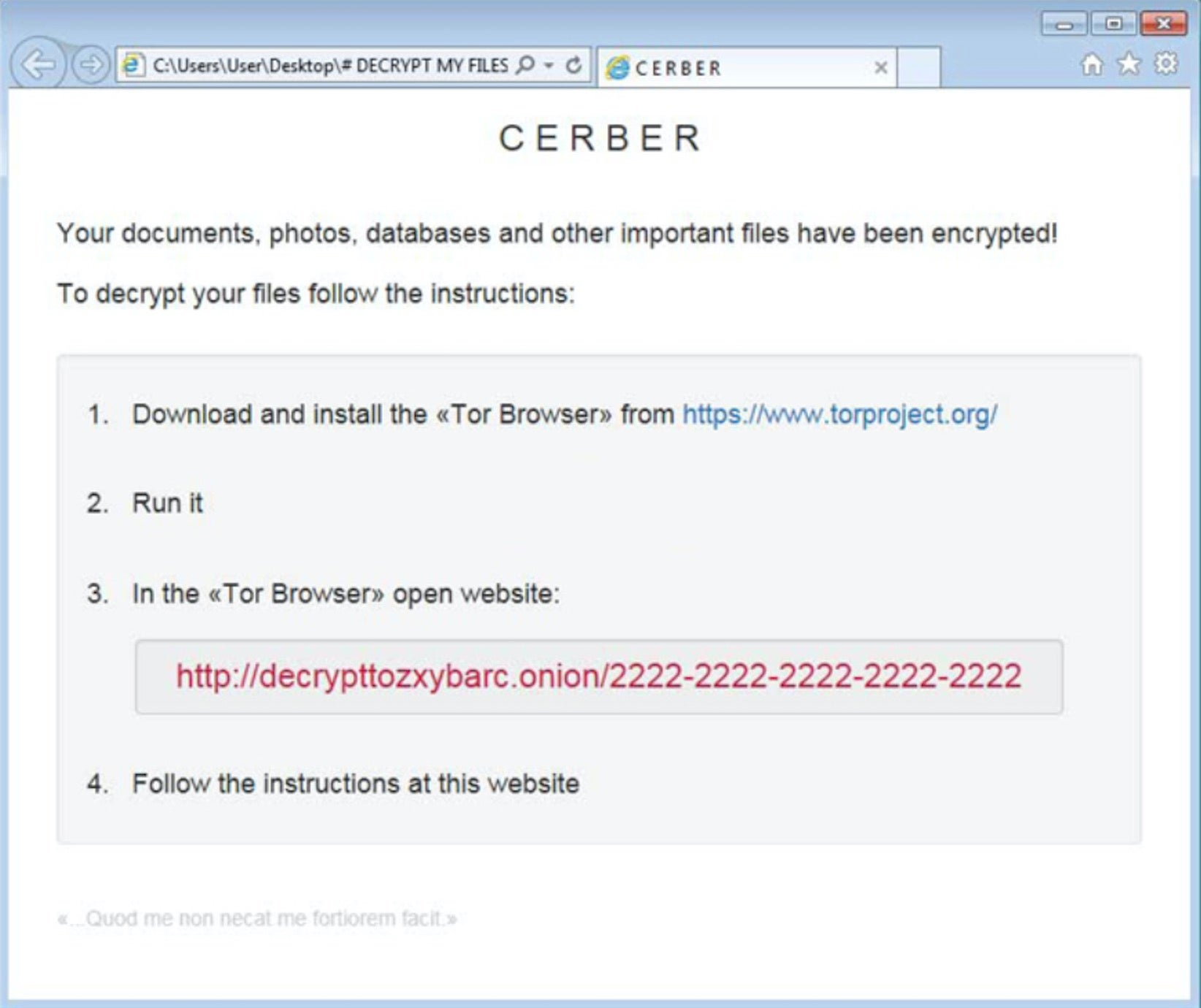

The Cerber ransomware used a VBScript to play an audio message that repeatedly announced “Attention! Your documents, photos, databases and other important files have been encrypted!”.

At the bottom of the Cerber ransom note pictured above, note the Latin dictum, “Quod me non necat fortiorem facit”, which translates to the more familiar “That which does not kill me, makes me stronger”. Quite why the attackers chose to include this little adage of fortitude remains a mystery; perhaps they thought it would help encourage some of their more educated victims to see the wisdom of paying!

But in terms of ensuring and expediting payment, the results were inconclusive (for a deeper dive into the psychological mechanisms used in ransomware splash screens, see this study sponsored by SentinelOne).

Waving a Bigger Stick

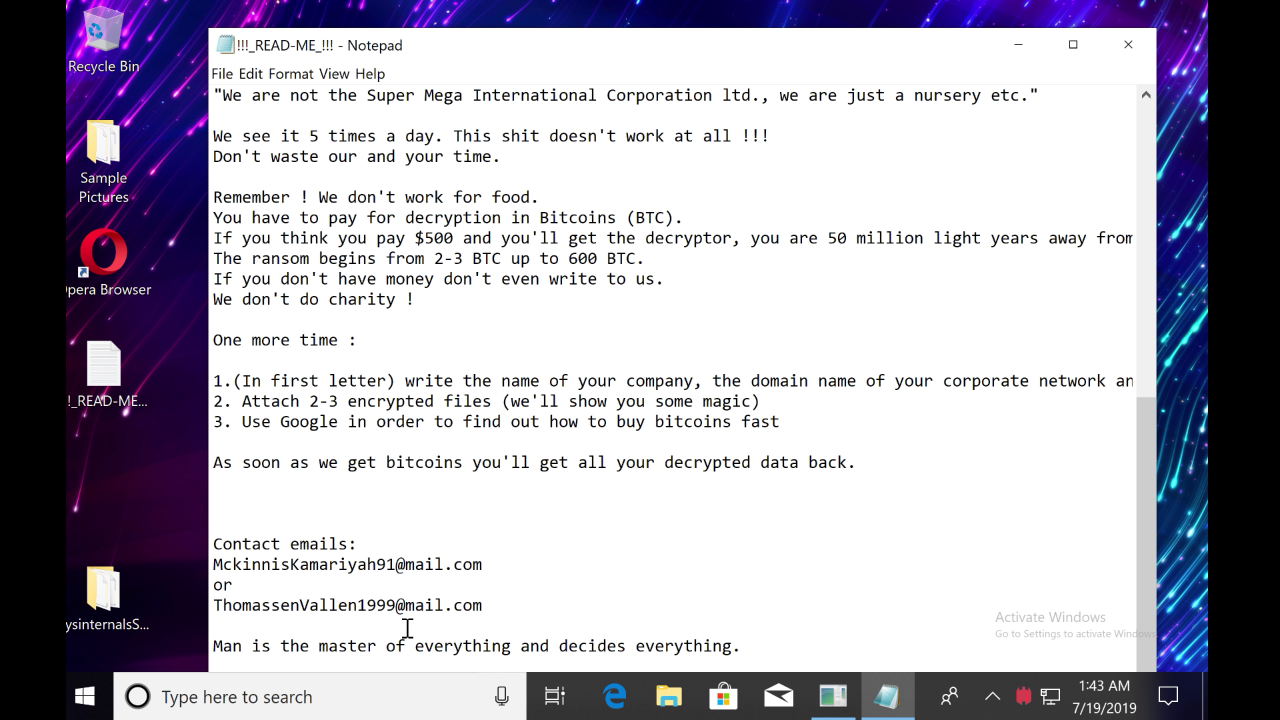

When threats and scare techniques were not enough to drive people to action (or at least not fast enough), ransomware attackers adapted their psychological ploys. Recent examples of ransomware take a variety of approaches, from showing much greater aggression, aimed at convincing people to pay the full sum instead of negotiating, to ‘soft sales’ with empathic concern.

A good example of the former is the ransom note of Megacotex, which warns victims not to try to send partial payment or to negotiate a discount, else they will never see their data again.

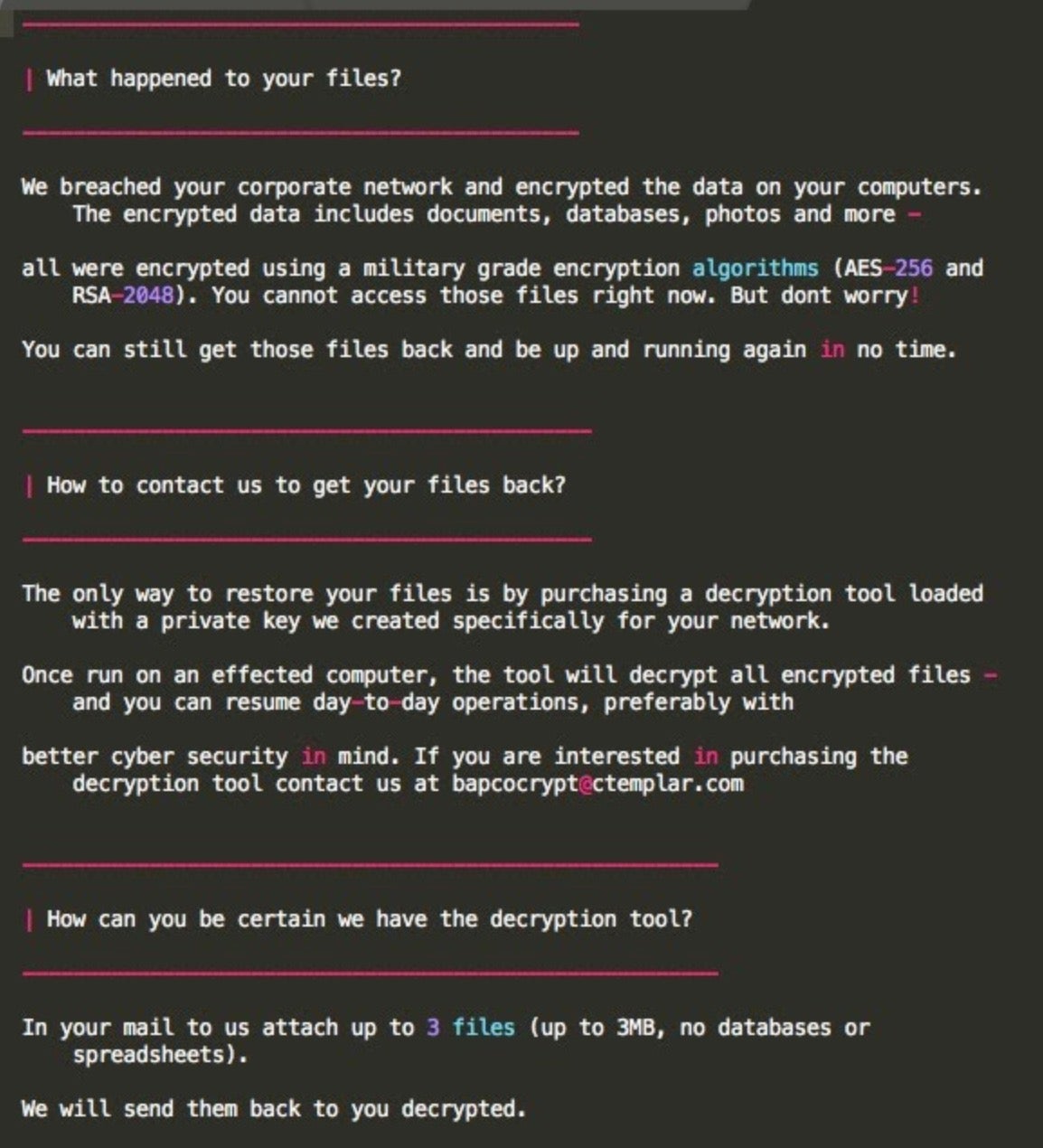

Other ransomware operators understand that different victims may require different psychological entreaties and instead opt for empathy. Snake ransomware for example, tries to come across as reasonable and concerned with a FAQ-style presentation and reassuring language like “don’t worry” and “you can be up and running in no time”.

Notably the “demand” shifts to the more familiar ‘soft’ marketing call to action of “if you are interested in purchasing…”. About all that’s missing from this as compared to a regular sales message is the offer of 0% interest-free financing!

Playing the Shame Game

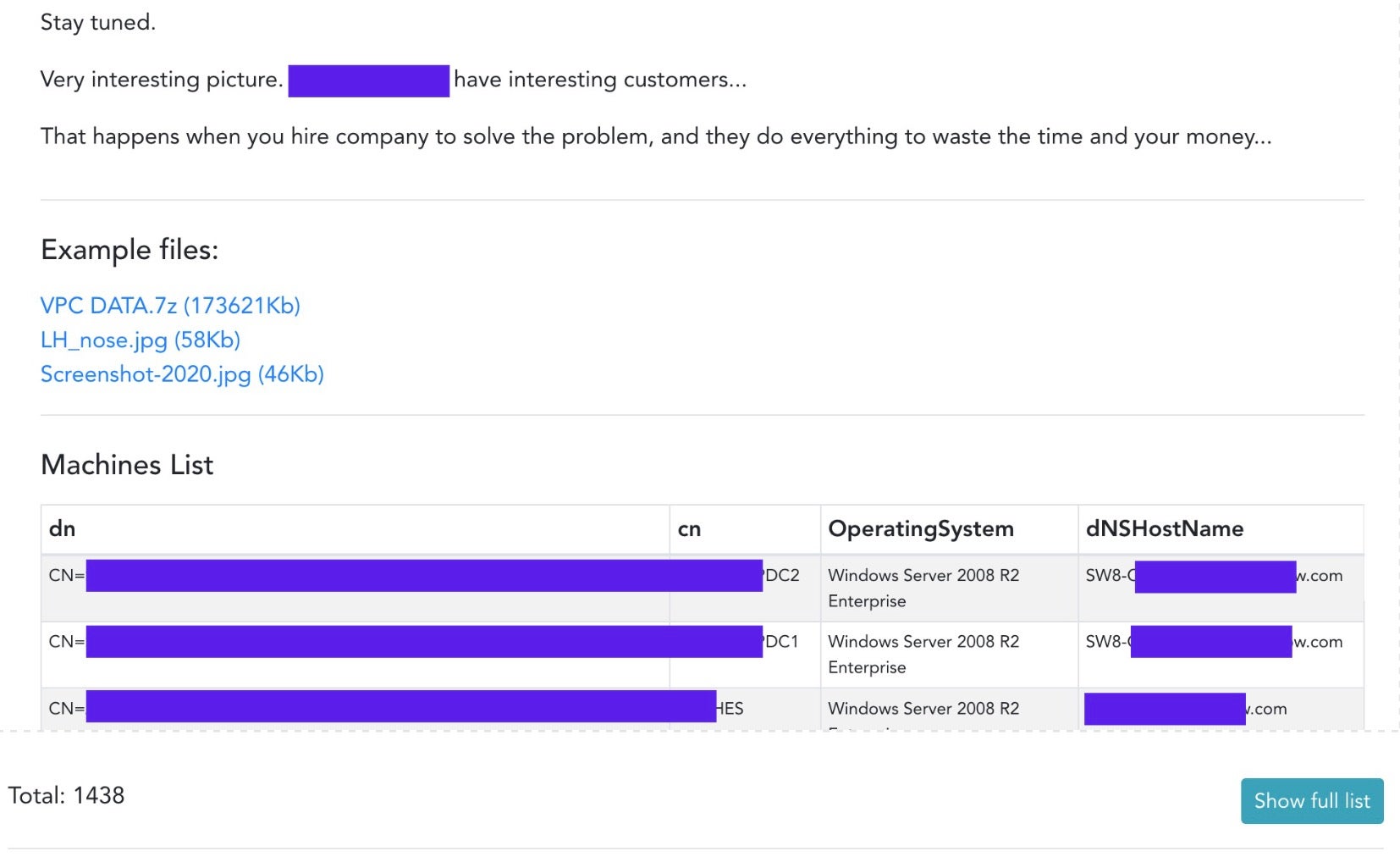

From sometime around 2013 or 2014, a number of more organized attackers began quietly exfiltrating victim data prior to encrypting it. Cerber ransomware was perhaps one of the first. But recently, we have seen a growing shift in using the exfiltrated data directly as a method of coercion. The technique was perhaps first used by Maze ransomware, and now is also leveraged by DoppelPaymer, Sodinokibi and Nemty. This new twist involves setting up a publicly accessible website and exposing the data of uncooperative victims.

The technique of threatening the victims with the publication of their sensitive data if they don’t pay turns the screw ever more tightly by discouraging victims from seeking out decryptors or avoiding making payment by restoring from backups. Now, even if the victim can recover, the threat of their data being exposed may still convince them to pay up.

When Script Kiddies Play with Ransomware

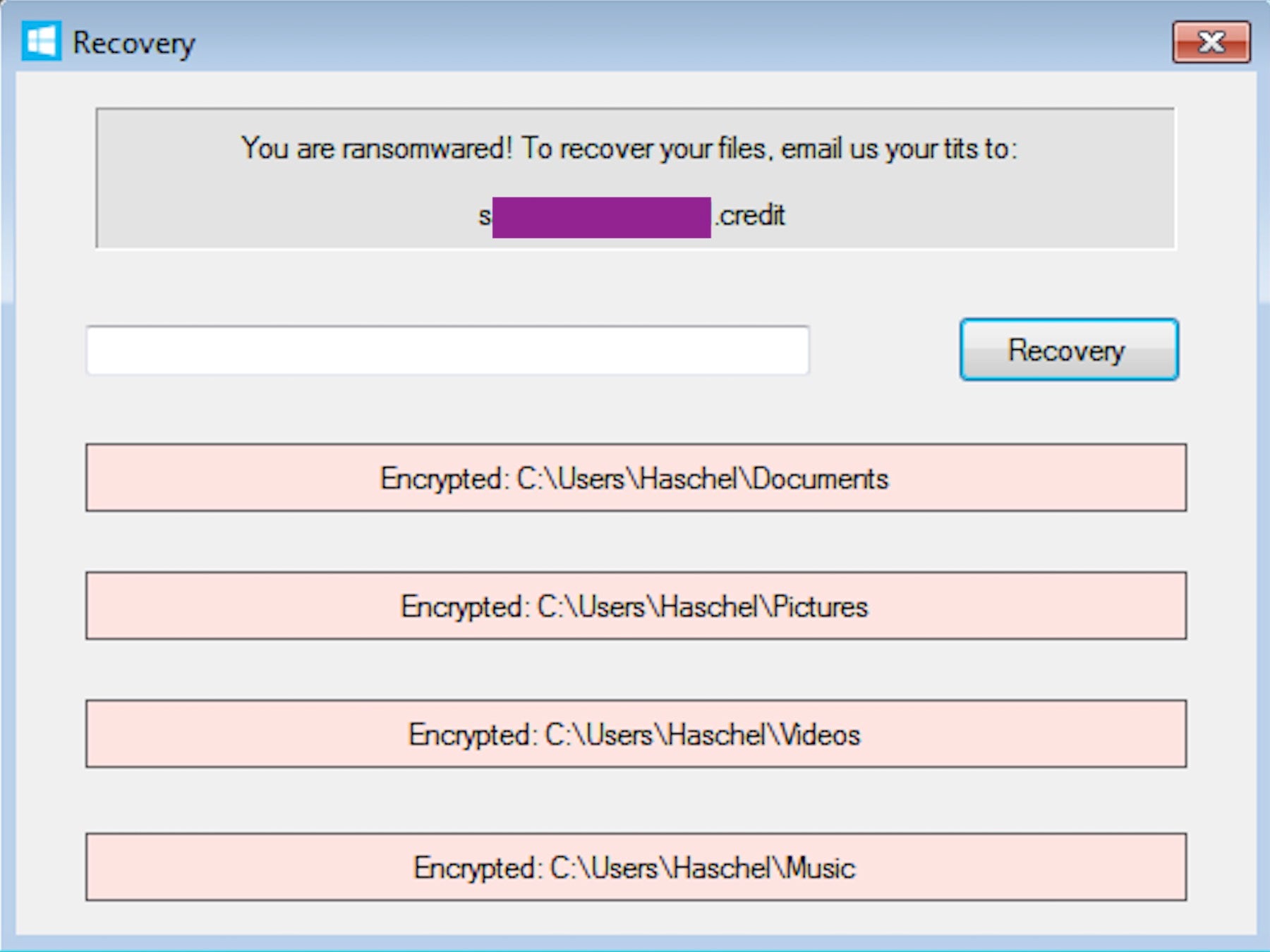

Last but not least, and what to some could be the most sinister of all, one recent variant combines ransomware with sextortion, and demands payment in nude photos instead of Bitcoins. The malware shows a message requesting the victims to send nude images to a specific email address in order to recover their files.

Most likely the work of children or adolescents and with a public decryptor already available, it’s nevertheless a prime example of how ransomware code is now in the hands of anyone with malicious intent.

Conclusion

The psychological impacts of cybercrime, and ransomware in particular, are profound. For many victims it results in worry, anguish, disbelief, and a sense of helplessness. Typically, those who have experienced this kind of cybercrime report that the effects last months after the actual incident. In this regard, ignorance might actually be bliss for victims, but sadly, this is one facet that ransomware victims will continue to suffer from in the foreseeable future.

As we have seen, with ransomware operators increasingly willing and able to exfiltrate data prior to encryption, organizations can now no longer rely on even having a good backup policy as an effective means to mitigate the threat of ransomware. The only sure defense is to stop the breach occurring in the first place, and for that you need a trusted, automated behavioral AI solution watching your back. If you’d like to see how SentinelOne can help protect your organization from the ransomware threat, contact us today or request a free demo.