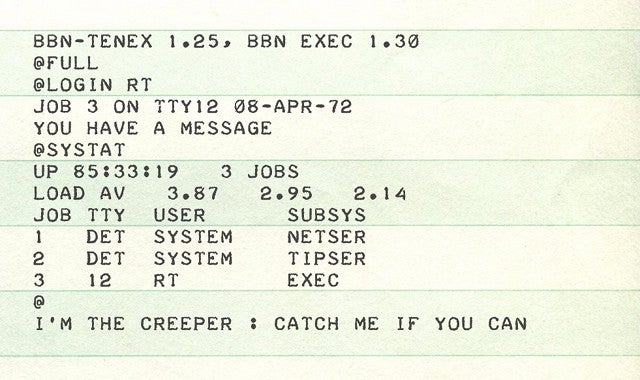

The history of cyber security began with a research project. A man named Bob Thomas realized that it was possible for a computer program to move across a network, leaving a small trail wherever it went. He named the program Creeper, and designed it to travel between Tenex terminals on the early ARPANET, printing the message “I’M THE CREEPER: CATCH ME IF YOU CAN.”

A man named Ray Tomlinson (yes, the same guy who invented email) saw this idea and liked it. He tinkered with the program and made it self-replicating—the first computer worm. Then he wrote another program—Reaper, the first antivirus software—which would chase Creeper and delete it.

It’s funny to look back from where we are now, in an era of ransomware, fileless malware, and nation-state attacks, and realize that the antecedents to this problem were less harmful than simple graffiti. How did we get from there to here?

From an Academic Beginning, a Quick Turn to Criminality

First of all, let’s be clear—for much of the 70s and 80s, threats to computer security were clear and present. But, these threats were in the form of malicious insiders reading documents they shouldn’t. The practice of computer security revolving around governance risk and compliance (GRC) therefore evolved separately from the history of computer security software. (Anyone remember the Orange Books?)

Network breaches and malware did exist and were used for malicious ends and cybercrime during the early history of computers, however. The Russians, for example, quickly began to deploy cyberpower as a weapon. In 1986, the German computer hacker Marcus Hess hacked an internet gateway in Berkeley, and used that connection to piggyback on the Arpanet. He hacked 400 military computers, including mainframes at the Pentagon, with the intent of selling their secrets to the KGB. He was only caught when an astronomer named Clifford Stoll detected the intrusion and deployed a honeypot technique.

At this point in the history of cyber security, computer viruses began to become less of an academic prank, and more of a serious threat. Increasing network connectivity meant that viruses like the Morris worm nearly wiped out the early internet, which began to spur the creation of the first antivirus software.

History of Cyber Security: The Morris Worm, and the Viral Era

Late in 1988, a man named Robert Morris had an idea: he wanted to gauge the size of the internet. To do this, he wrote a program designed to propagate across computer networks, infiltrate Unix terminals using a known bug, and then copy itself. This last instruction proved to be a mistake. The Morris worm replicated so aggressively that the early internet slowed to a crawl, causing untold damage.

The worm had effects that lasted beyond an internet slowdown. For one thing, Robert Morris became the first person successfully charged under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (although this ended happily for him—he’s currently a tenured professor at MIT). More importantly, this act also led to the formation of the Computer Emergency Response Team (the precursor to US-CERT), which functions as a nonprofit research center for systemic issues that might affect the internet as a whole.

The Morris worm appears to have been the start of something. After the Morris worm, viruses started getting deadlier and deadlier, affecting more and more systems. It seems as though the worm presaged the era of massive internet outages in which we live. You also began to see the rise of antivirus as a commodity—1987 saw the release of the first dedicated antivirus company.

The Morris worm also brought with it one last irony. The worm took advantage of the sendmail function in Unix, which was related to the email function originally created by Ray Tomlinson. In other words, the world’s first famous virus took advantage of the first virus author’s most famous creation.

The Rise of the AV Industry

A trickle of security solutions began appearing in the late 80s but the early 90s saw an explosion of companies offering AV scanners. These products scanned all the binaries on a given system and tested them against a database of “signatures”. These were initially just computed hashes of the file, but later they also involved searching for a list of strings typically found in the malware.

These early attempts at solving the malware problem were beset with two crucial problems that were never entirely solved: false positives and intensive resource use, with the latter being a major cause of user frustration as the AV scanner often interfered with user productivity.

At the same time, the number of malware samples being produced exploded. From a few tens of thousands of known samples in the early 90s, the figure reached around 5 million new samples every year by 2007. By 2014, it was estimated that around 500,000 unique malware samples were being produced every day. The (by now) legacy AV solutions were swamped: they simply couldn’t write signatures fast enough to keep up with the problem. A new approach was needed.

Endpoint Protection Platforms were the next step. Instead of relying on static signatures to identify viruses, they introduced the use of signatures scanning for “malware families”. The fact that most malware samples are a deviation of existing samples worked well for EPP solutions, as they were able to prove to customers they could prevent the “unknown”, which was in fact detections based on existing malware that their signatures could recognize.

EternalBlue: Lateral Movement Comes to Play

Lateral movement techniques are ways for attackers to issue commands, run code and spread across the network. These are not new to most sysadmins, but thanks to a leak of NSA hacking tools, it turns out that some operating system protocols have had vulnerabilities in them for many years that allow cyber criminals to achieve stealthy lateral movement. One notable example is what we now know as “EternalBlue”.

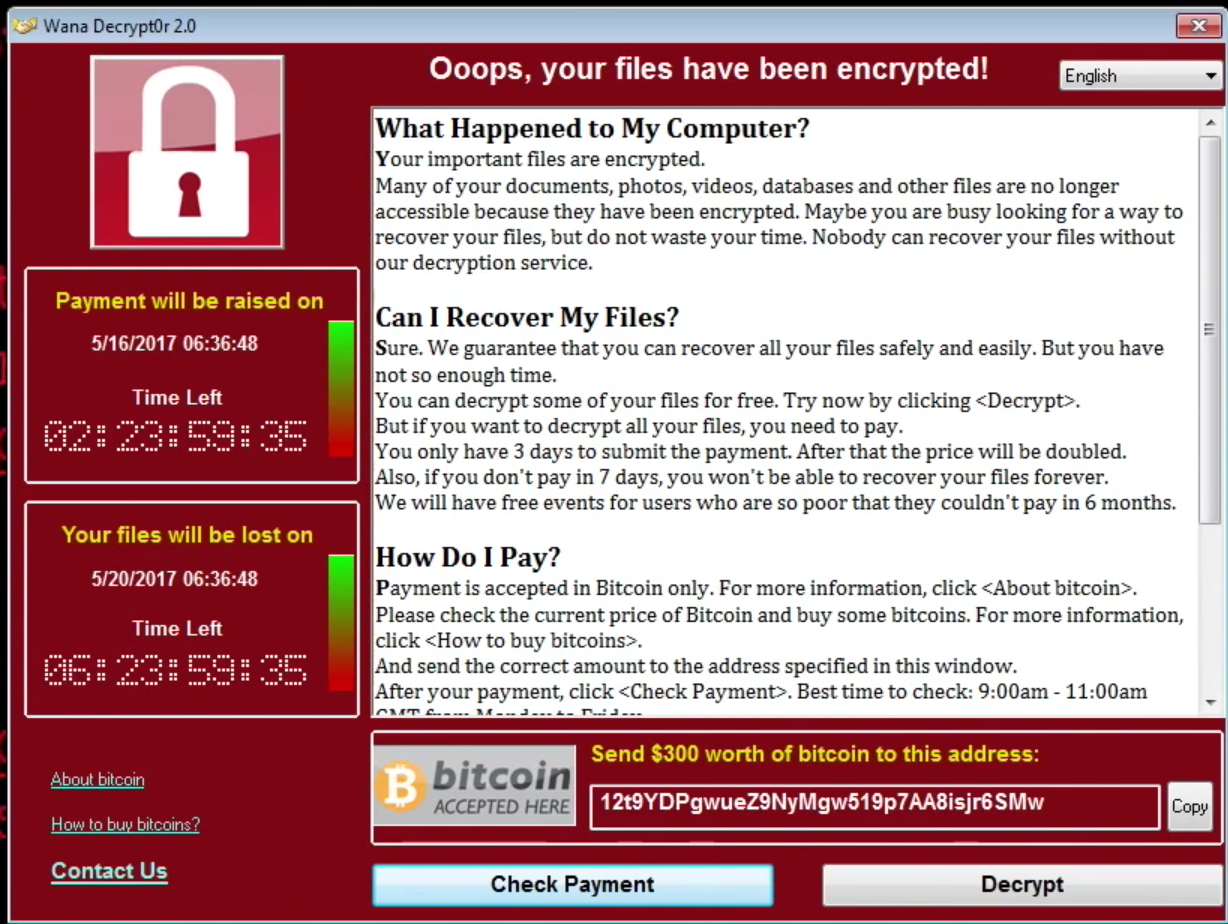

EternalBlue exploits the SMB protocol used for file sharing over the network. This makes the protocol highly attractive to adversaries. EternalBlue was leaked by the Shadow Brokers hacker group on April 14, 2017, and was used as part of the worldwide WannaCry ransomware attack on May 12, 2017. The exploit was also used to help carry out the 2017 NotPetya cyberattack on June 27, 2017 and reportedly is used as part of the Retefe banking trojan since at least September 5, 2017. No Anti-Virus or even next generation EPP can effectively prevent exploitation using EternalBlue.

Fileless malware and system vulnerabilities are just two of a number of common ways that attackers can bypass traditional antivirus (and also more than a few “next-gen” endpoint solutions). So if your company’s reputation is on the line and you can’t guarantee protection, what can you do? That’s right. You find ways to make sure you are aware of what’s going on with your assets. The new name of the game is Detection.

WannaCry and the Dawn of The Age of Ransomware

It didn’t take long for adversaries to figure out how to defeat EPP solutions. Fileless malware leveraging built-in tools like VBScript, PowerShell, Office Macros and DDE attacks can easily avoid signature-based EPP solutions. This was proved with devastating effect by WannaCry.

It’s hard to recall a bigger shock to the IT community than WannaCry, “the biggest ransomware offensive in history.” Within 24 hours, WannaCry had infected more than 230,000 computers in over 150 countries.

From a technical point-of-view, it was not particularly sophisticated. In fact, it exploited a vulnerability that had been known for 91 days and that had already been patched by Microsoft.

Even so, an estimated 1.3 billion endpoints were eventually infected. In the UK, the National Health Service – a major client for Sophos – had to cancel 20,000 appointments and operations due to the ransomware. Whether any lives were lost as a result of it will never be known, but what is known is that it crippled the country’s health service.

After a brief lull, the ransomware menace continued to explode in the years immediately following WannaCry. Attackers expanded both their techniques and their demands.

In terms of techniques, threat actors of all shades and colors saw how they could combine fileless, PowerShell, and phishing techniques to hit victims with a variety of malware, at times using platforms like Emotet and TrickBot to infect victims with multiple malware stages and achieve several objectives simultaneously. A few examples:

- Using a PowerPoint to run malicious code

- Using a Microsoft Word to run malicious code

- Installing trojans that can use your computer resources to mine cryptocurrency

- Using email spam to trick users

Often crimeware operators would use a dual strategy of mass, indiscriminate attacks followed up by more targeted intrusions on selected targets from the first wave. Organizations running vital infrastructure and public services became favored targets both because they often lacked the budget and expertise to maintain effective security operations and because the critical nature of their services meant they could not tolerate lengthy outages.

Ransomware operators also began to realize that they could leverage victims more effectively by first stealing data before encrypting it. Ransom notes then came not only with a demand for payment, but also a threat to leak or sell the stolen data if the victim didn’t pay. In effect, this strategic response nullified organizations’ attempts to protect themselves in the wake of WannaCry merely by ensuring they had offline backups.

From Prevention to Detection: EDR Was Born

Earlier in the cybersecurity timeline (and to some extent even today), companies hired Incident Response teams to come in and investigate security breaches. In 2013, the most reliable among these was Mandiant. They offered cybersecurity professionals that were always ready to jump in and find out what had happened. And they were not cheap.

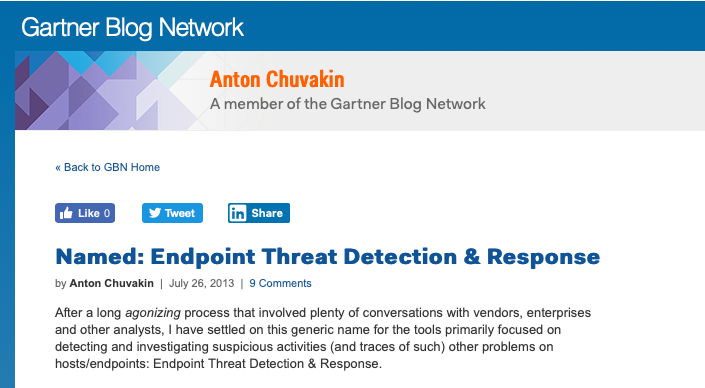

In parallel, some more technical enterprises had begun to invest in visibility tools like Facebook’s osquery and other ways to see into networks. That opened up a new category for the overcrowded market of cybersecurity, and many new solutions were created as a result. Gartner’s Anton Chuvakin coined the term “EDR” to describe this family of new tools focused on visibility.

With that revolution, the inherent problems of EDR solutions started raising their heads.

Enterprises needed a highly skilled crew to manage these solutions as they provide so much data, but lacked so much of the context. Enterprises found themselves hiring more and more information security and cybersecurity professionals to solve this problem, but the past couple of years have seen barely a month go by without the news headline of yet another high-profile data breach.

The other critical problem in the area of EDR revolves around “dwell time”. Dwell time represents the time from the infection to the discovery of the malicious activity. Some have suggested an average 90 days dwell time – hardly acceptable to any enterprise – and more recently some products claim they can reduce dwell time to a matter of minutes. Putting aside how reliable self-made claims like these might be for a moment, even 10 seconds is much too long: attackers can run their code, execute their attack, and wrap it up and clean themselves out in a matter of just a few seconds. Any solution that is not detected in real-time is too late in the game.

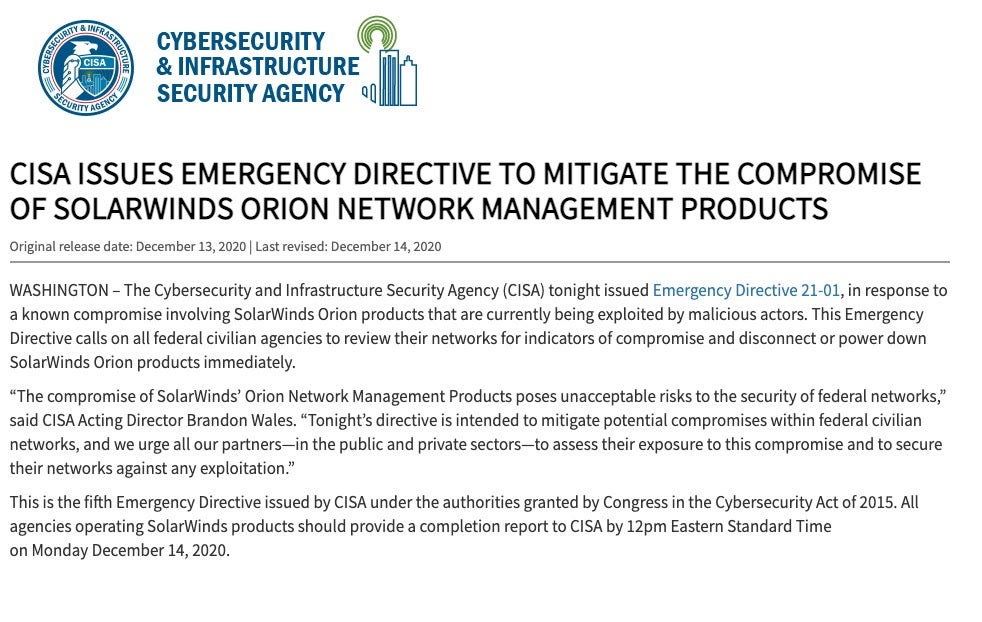

SolarWinds & the SUNBURST Attacks | The Supply Chain Cracks

In late 2020, a massive breach was disclosed affecting the SolarWinds Orion platform. Orion is a management and performance monitoring platform aimed at streamlining and optimizing IT infrastructure. First notice of a problem came via cybersecurity company FireEye, one of a number of well-known security companies that were victims in the SolarWinds compromise. That, however, was just the tip of the ongoing iceberg of effects. SolarWinds’ massive install base ranged across some of the most high-value entities across the United States, including government and critical infrastructure.

The attack, like many before it, was long-term and very deliberate with regards to weaponization and delivery of malicious implants and artifacts. The original disclosure from FireEye was published in early December 2020. However, current analysis indicates that the roots of the attack go all the way back to mid-to-late 2019. Backdoor components were found dating to at least October 2019, while the primary poisoning of SolarWinds’ update infrastructure appears to have occurred between March and May of 2020.

The main backdoor injected into the SolarWinds’ build system came to be known as the SUNSPOT backdoor. In order to maintain stealth and bypass certain analysis techniques, the malware was programmed to lay dormant for 12-14 days after delivery. Upon installation, numerous environmental checks would be performed, including exit procedures if specific network security tools such as SentinelOne were found to be protecting the device. It is believed that this ‘quit and run’ strategy allowed the attackers to both stay undiscovered for longer and to better target specific systems with a higher-probability of successful compromise.

Once the attackers gained their foothold, additional components and tools were introduced into the attack. These included Cobalt Strike Beacon payloads, additional dropper malware (TEARDROP), along with various PowerShell scripts and more.

While in the target environments, the attackers were able gain unauthorized access to highly sensitive and confidential information. This included product source code repositories, proprietary corporate data and intellectual property, as well as personally identifiable information.

Since the disclosure of this attack, and the resulting fallout, there has been increased scrutiny of the internal security practices of enterprise software and service providers, as well as trusted security partners who appeared to have been targeted or compromised (including CrowdStrike, Microsoft, Mimecast and MalwareBytes).

Current estimates indicate that approximately 18,000 victims were directly affected by the campaign. It is assumed that as we proceed into 2021, findings and details will evolve and the true scope of this issue will be even more apparent. Overall, attacks like this can severely undermine trust in even the most esteemed service providers and partners.

Protect Yourself from Modern-Day Threats with SentinelOne

Cyber threats have come a long way since the invention of the Morris worm, and Russian and other nation-state hackers have honed their skills since the days of Marcus Hess, as clearly demonstrated by the SolarWinds’ supply chain attack. To counter these modern threats, companies need future-proof systems and data protection, and that’s where SentinelOne comes in.

No matter what techniques your adversaries are using, SentinelOne can detect and mitigate them using a lightweight machine-learning algorithm and smart automation. Our solution was given the 2019 Gartner Peer Insights Customers’ Choice for Endpoint Detection and Response Solutions and the 2018 Gartner Peer Insights Customers’ Choice for Endpoint Protection Platforms.

At machine speed, SentinelOne’s ActiveEDR is able to prevent, detect, and respond to advanced attacks regardless of delivery vectors, whether the endpoint is connected to the cloud or not. The SentinelOne solution can provide a security team, small or large, regardless of skill level, with the context to not only understand what is found, but to autonomously block attacks in real time.

We created ActiveEDR as a response to the problems our customers faced, and they have reacted with a resounding “Wow!” to the difference it makes.

The future of EDR is ActiveEDR, and it’s already here! contact us for a personalized free demo.