Last week, the iOS jailbreaking community was set abuzz after security researcher axi0mX dropped what’s been described as a ‘game changing’ new exploit affecting Apple’s mobile platform. Dubbed ‘checkm8’, the Boot ROM exploit has widely been proclaimed as the most important single exploit ever released for iPhone, iPad, Apple TV and Apple Watch devices. But what does that actually mean for the security of the millions of affected iOS devices out there, in use in both personal and enterprise environments? In this post, we look behind the headlines and the inevitable FUD to break it all down and answer the essential questions.

1. Are iOS Devices Now Insecure Because of checkm8?

No, let’s get clear about this. For almost all realistic scenarios of in-use devices, Checkm8 hasn’t “changed the game” in terms of risk management. That’s not to say the Boot ROM exploit isn’t hugely important – it is, as we’ll explain below – but the ways in which this exploit can be used by attackers are few and limited.

First, there’s no remote execution possibility here. An attacker cannot use checkm8 to compromise an untethered device. That means anyone wanting to use this exploit without having the target device physically in their possession is out of luck.

Second, checkm8 does not allow a threat actor to bypass TouchID or PIN protections. In other words, it does not compromise the Secure Enclave. That means your personal data remains safe from attackers who don’t have your unlock credentials, notwithstanding the possibility of other zero days.

Third, there’s no persistence mechanism here, either. If an attacker gained possession of your device and used the Boot ROM exploit to compromise it, re-booting the device would bring it back to a healthful state. Any changes made by the attacker would be lost as Apple’s security checks would either delete the files modified by the attacker or refuse to run them.

2. What Should I Do To Stay Safe from checkm8?

With that said, checkm8 does mean security-conscious users should consider the possibility of a potential hack or malware infection if the device has been out of their presence or physical control.

If you’ve left your iPhone unattended and powered-on in your hotel room, for example, or on a desk in shared office space, or had it temporarily confiscated by border security guards, say, you should re-boot your iOS device when it comes back into your possession. And for good measure, you should probably do a force restart to ensure that malware hasn’t found a way of simulating a fake reboot.

All that’s probably advice that you should already have been heeding anyway, as there’s been speculation of privately-held hacks and iOS zero days swirling around at least since the infamous San Bernardino, FBI vs Apple story back in 2016. Checkm8 means we now have a publicly-known and available exploit that could have been used in that kind of situation.

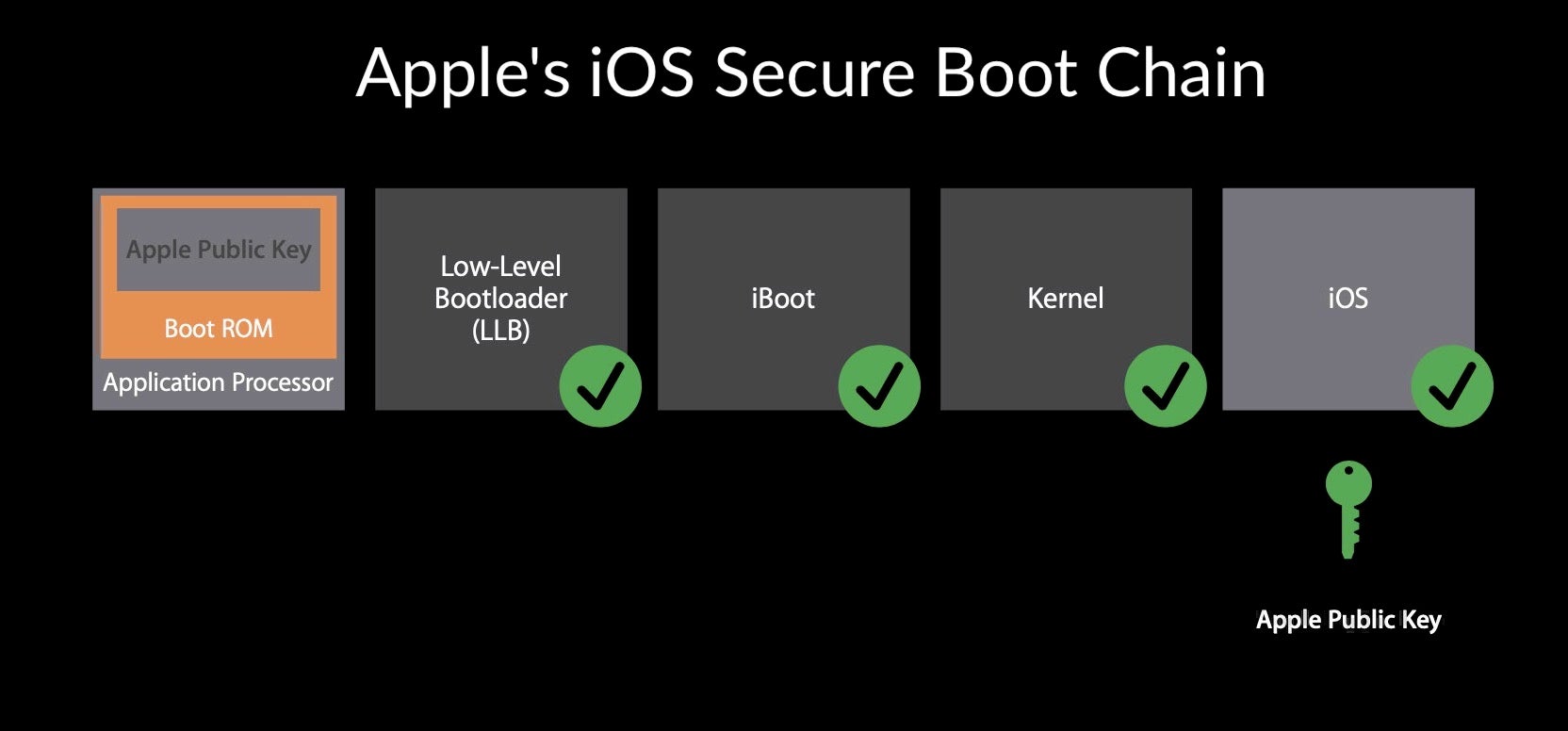

The following graphic taken from Apple’s WWDC 2016 presentation shows the flow of the secure boot chain from power on, from left to right, on an uncompromised device.

According to the iOS Security Guide:

“Each step of the startup process contains components that are cryptographically signed by Apple to ensure integrity and that proceed only after verifying the chain of trust…This secure boot chain helps ensure that the lowest levels of software aren’t tampered with.”

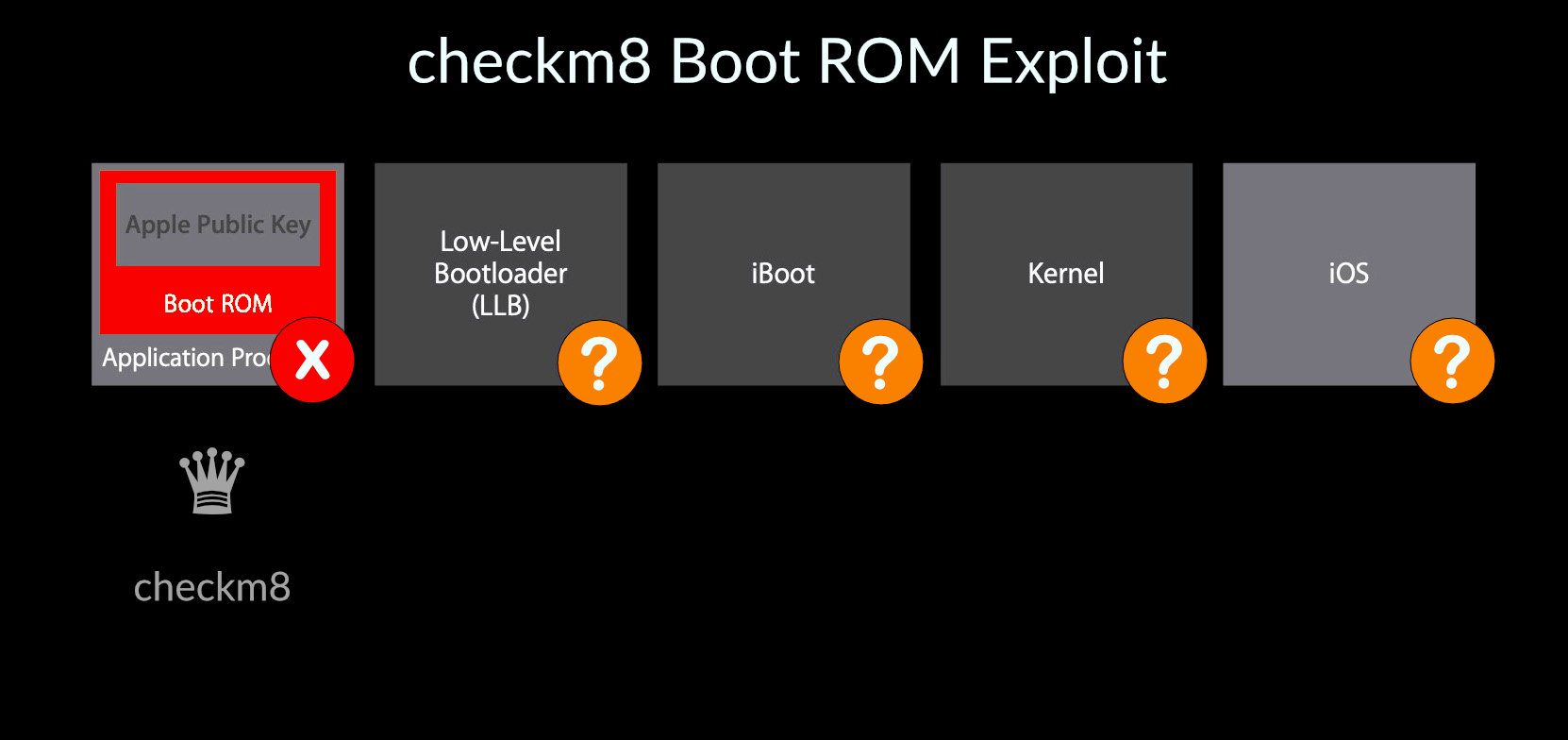

What makes checkm8 so devastating is that it exploits flaws right at the beginning of this process, thus undermining all further checks made by subsequent steps in the chain.

3. Which iOS Devices Are Affected by checkm8?

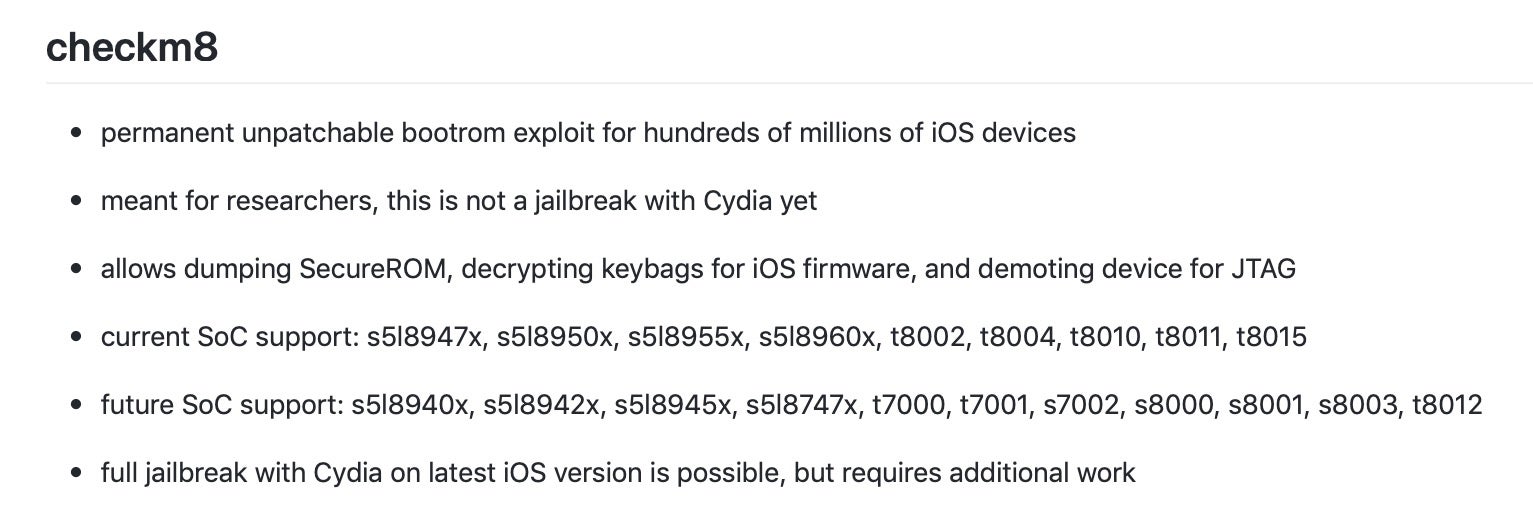

While not every iOS device is affected by checkm8, the vast majority in use are. If you own, or purchase, an iPhone XR, XS, XS Max or any of the iPhone 11 series, all of which use the A12 Bionic or later chip, then the Boot ROM exploit will not work on it. That’s because the use-after-free vulnerability that axi0mX found appears only in devices using A11 chips or earlier, which includes iPhone 4S to iPhone X models, as well as any iPad, Apple TV or Apple Watch device using A11 or earlier chips.

Most generations of iPhones and iPads are vulnerable: from iPhone 4S (A5 chip) to iPhone 8 and iPhone X (A11 chip).

4. How Does checkm8 Change the Game for iOS Security?

As we’ve already explained, for end users concerned about the practical security of their devices on a day-to-day basis, there isn’t really anything particularly new to worry about it here. However, this exploit really is a game changer for researchers and, to a certain extent, for Apple itself as well as for some developers. That’s because with checkm8, anyone will be able to jailbreak their iOS device and inspect what’s going on ‘under the hood’ with any software that’s running on it.

For example, unscrupulous developers are now on notice that it’s only a matter of time before security researchers start to uncover any underhand behaviour or functionality in their apps that Apple’s code review might have missed. My prediction is that in the coming months we will see quite a few startling revelations of devious behaviour by so-called ‘reputable’ apps as more and more researchers begin jailbreaking devices and reverse engineering apps to examine how particular applications behave at runtime.

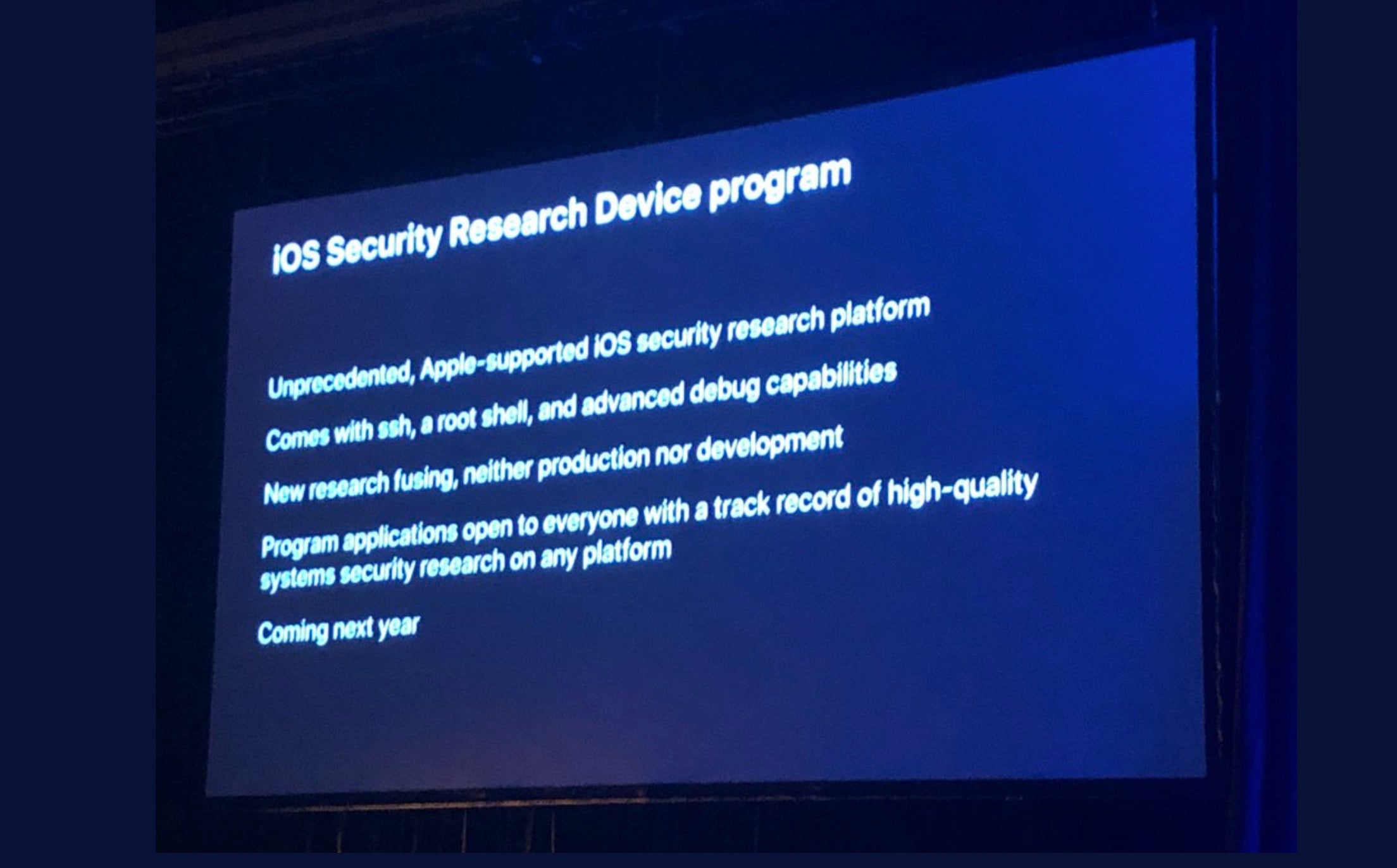

The second, massive ‘game changing’ aspect of checkm8 is the one that most people have been talking about this weekend: it means we will not have to depend on Apple’s generosity in handing out special ‘research’ phones to a select few researchers in order to explore iOS itself for more bugs and security flaws. The iOS Security Research Device program was slated to commence in 2020, but it now appears to be effectively redundant. It remains to be seen if there’s any point now in Apple following through with it.

As a result of checkm8, there will be a huge increase in the actual number of people actively investigating iOS security. Assuming Apple don’t now change their minds about offering an expanded bug bounty program, that means we should see a real acceleration in finds of crucial bugs in the iOS operating system itself.

That, again, is a great thing for iOS security. As the old saying goes, security by obscurity is no security at all, and checkm8 really brings the inner workings of iOS out into the light for inspection by anyone, not just a handful of chosen researchers.

5. Will Apple Release a Security Patch to Fix checkm8?

No, that’s not going to happen for the simple reason that security updates cannot fix flaws in the Boot ROM code. The flaw is “baked in” at the factory and could only be fixed, perhaps, by a recall of affected devices. Given the cost to Apple of doing that versus the benefit, that’s extremely unlikely to happen.

This means that affected devices are vulnerable “forever”. Of course, there’s a shelf-life for how long these devices will be upgradable to the latest version of iOS, perhaps as much as 5 years from manufacture in some cases. That gives researchers a great opportunity to thoroughly explore how iOS works from now and into the mid-term future. Beyond that, although these devices will themselves still be vulnerable, once they are unable to run the latest version of iOS, we will once again be back to the ‘dark ages’ of not knowing what running code is doing on our iOS devices.

Conclusion

The main takeaway from the checkm8 Boot ROM exploit released last week by axi0mX is that while it doesn’t change much for users in terms of how they should manage risk in practical terms, it does change pretty much everything for researchers in terms of giving them unprecedented, privileged access to the inner workings of iOS and, indeed, 3rd party code running on their devices.

While there have been some voices in the media suggesting that these kind of exploits should not be made public, it’s hard to see how the net benefit of this won’t be a huge positive for users, researchers and Apple itself. The more people hunting bugs on iOS the better for everyone, and the checkm8 exploit is arguably only doing what Apple themselves had this year promised to do by providing ‘research’ phones and an expanded bug bounty program; namely, opening up iOS bug hunting to a larger – a very much larger – community of researchers.