Last week, we recommended how companies could reduce their payouts from ransomware by forming a pricing cartel.

This week, we discuss issues in cyber insurance in light of increasing nation-state cyber threats.

Please subscribe to read future issues — and forward this newsletter to interested colleagues.

Contact us directly with any comments or questions: [email protected]

PinnacleOne ExecBrief | Are You Actuarially In Good Hands?

Cyber insurance has matured as a product over the last few years, but large uncertainties remain around what the industry terms the “aggregation risk” of “systemic events” associated with state-directed cyber attacks. These events, driven by state actors or affiliates, pose significant challenges for insurers, as the potential for widespread disruption across multiple sectors and regions creates a risk that is difficult to measure, predict, and mitigate.

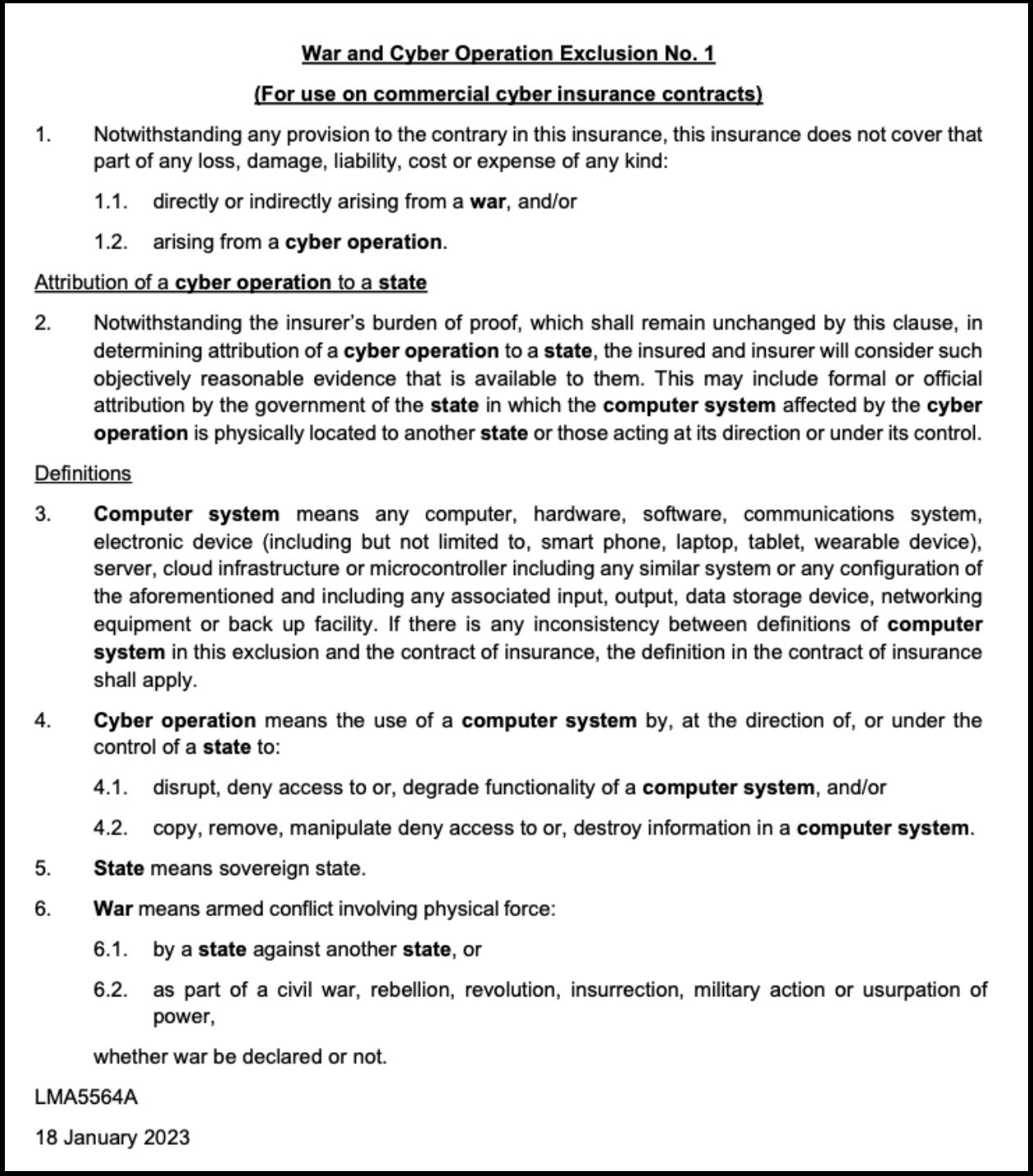

Published in August 2022 on the heels of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Lloyd’s Market Bulletin Y5381 introduced a significant shift in cyberattack insurance policies, mandating exclusions for state-backed cyberattacks starting from March 2023. These policies were required to rule out coverage for cyberattacks tied to government actions unless explicitly agreed otherwise. Lloyd’s wrote at the time:

The exclusions applied to cyberattacks that disrupted essential state functions or security, and insurers had to create clear processes to attribute these attacks to specific states. While the move aligned Lloyd’s with major players like Munich Re, it created potential conflicts with non-Lloyd’s insurers and raised concerns about gaps in coverage.

By January 2024, the gravity of these exclusions was underscored by a congressional hearing on the Volt Typhoon, a Chinese hacking operation. U.S. cyber authorities warned of China’s plans to target critical infrastructure in the event of armed conflict to deter American military engagement. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) believes that disrupting civilian infrastructure could dissuade both U.S. leaders and the public from supporting military action. This threat is especially concerning as most critical infrastructure in the U.S. is privately owned, with operators resisting government regulation.

Even after the release of National Security Memorandum-22, which sought to boost critical infrastructure security, the government’s ability to enforce meaningful change was limited. Federal purchasing requirements were the only leverage to encourage compliance with minimum security standards.

Despite some infrastructure operators ignoring government warnings, insurers were acutely aware of the risks. With billions of dollars at stake, insurance companies closely followed the developments in state-backed cyber threats, particularly from China. Lloyd’s 2022 policy changes — excluding state-backed cyberattacks from coverage — became even more relevant as companies faced growing risks from global cyber warfare.

As these cyber threats have intensified, disputes over attribution, vague terms like “major detrimental impact,” and the broad language of exclusions remain significant issues. This has put the onus on businesses to reevaluate their cyber defenses and insurance policies, as insurers moved to protect themselves from the potentially devastating costs of a state-backed cyberattack.

A recent report by a cyber insurer noted that while “worst-case scenarios have not yet come to pass…risks associated with cyber warfare and systemic events more generally – scenarios where single attacks trigger widespread failures across multiple organizations – remain a concern.” They flagged that “the risk of and uncertainty around aggregation continues to hang over the market by impeding capital inflows and tempering risk appetite.”

Attribution is Key

The main issue likely to cause disputes between insurers and policyholders is the attribution of cyberattacks. Determining whether a cyber operation occurred, based on “objectively reasonable evidence,” is often contentious. The process for establishing sufficient evidence is unclear, and the covert nature of cyberattacks makes it difficult to determine state responsibility. States may use third parties, like cybercriminal groups, to conduct attacks, further obscuring the source.

Even when a state attributes a cyberattack to another, this information might not be publicly disclosed due to political or diplomatic sensitivities. A state could withhold attribution if releasing it would have significant financial consequences for insured businesses. Moreover, a state may attribute an attack based on political motivations rather than hard evidence, which can complicate the situation. It is also unclear whether attribution must come from the executive or legislative branch, or whether statements from intelligence or military agencies suffice.

Additionally, the definition of “major detrimental impact” remains vague, which could lead to disagreements over what qualifies as significant disruption. The broad language of the exclusion clauses, covering both direct and indirect losses, may limit coverage substantially depending on the event. This raises questions about whether the Lloyd’s model clauses adequately meet the requirement to provide a clear and robust attribution process and clearly define key terms. Given these ambiguities, careful review of cyber policy wordings is crucial to reduce the risk of disputes over cyberattack claims.

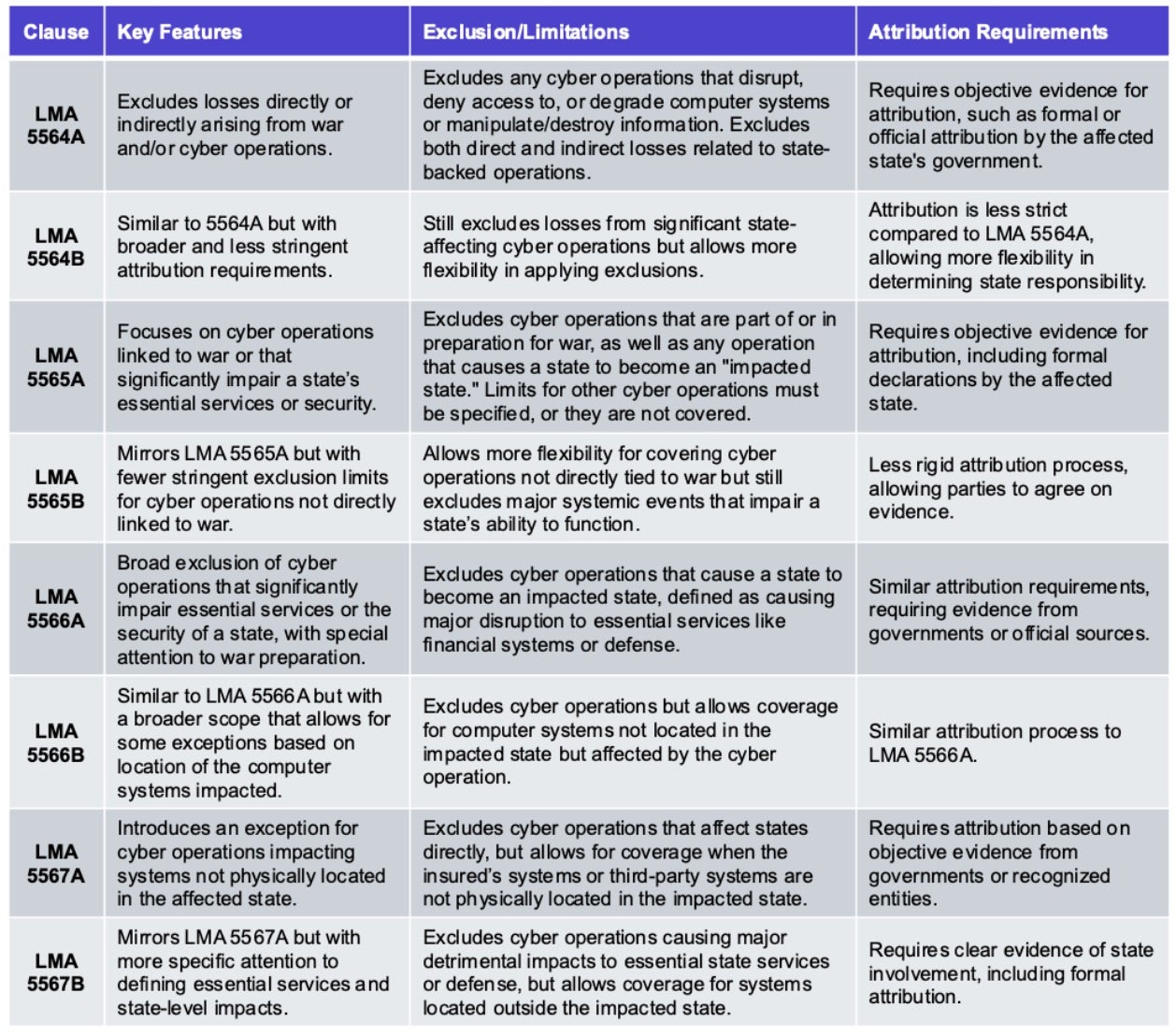

There are a number of variants of such clauses that offer different exclusions based on different attribution requirements and scope of coverage. The devil is truly in the details here…

Risk Lurking in the Tails

Attacks like those seen in the SolarWinds and Microsoft compromises illustrate how state-directed cyber operations can have far-reaching effects, crossing borders and impacting a wide array of industries. The recent MOVEit, Change Healthcare and NHS incidents showed how attacks on a single critical software, firm, or government service can cascade across the economy, creating systemic aggregate losses.

As insurers step away from covering cyber warfare-related risks, the question of responsibility looms. With the federal government acknowledging that it cannot effectively deter state-backed cyber intrusions, businesses are increasingly left in a precarious position. Top agency officials from both the NSA and FBI have admitted the grim reality: China, one of the leading perpetrators of cyber operations, cannot be deterred from targeting U.S. critical infrastructure.

NSA Assistant Deputy Director for China, Dave Frederick, noted in late August 2024 that China’s continued intrusions are inevitable. FBI Deputy Director Paul Abbate echoed these sentiments, acknowledging that no measures taken so far have deterred China’s actions, nor are there clear solutions for reducing these intrusions.

Businesses must now contend with a new reality where neither governments nor insurers can fully shield or cover them from nation-state attacks. It’s up to private firms to understand and own this risk and put in place sufficient security measures to defend themselves.