Last week, PinnacleOne collaborated with SentinelLabs to unpack the leak of internal files from a firm (I-Soon) that contracts with Chinese government security agencies to hack global targets.

In this ExecBrief, we examine how I-Soon (上海安洵) fits into the larger Chinese hacking ecosystem and highlight key implications for business leaders.

Please subscribe to read future issues— and forward this newsletter to your colleagues to get them to sign up as well.

Feel free to contact us directly with any comments or questions: [email protected]

Insight Focus | China’s Hacking Ecosystem

The leak of I-Soon’s internal files provided security researchers concrete details revealing the maturing nature of China’s cyber espionage ecosystem. The files–including chat logs between hackers offering pilfered data and complaining about poor compensation–showed explicitly how government targeting requirements drive a competitive marketplace of independent contractor hackers-for-hire. [PinnacleOne’s own Dakota Cary was in demand last week, quoted for comment in the FT, CNN, BBC, AP, Bloomberg, NBC News, NPR, Newsweek, The Record, Cyberscoop, KrebsonSecurity, DarkReading, and more.]

This company is one of many that contract with government agencies, including the Ministry of Public Security, Ministry of State Security, and People’s Liberation Army. As China’s appetite for foreign data and ambitions to become a global cyber power have grown, so has this burgeoning private industry of hackers-for-hire and an associated market for a torrent of stolen information.

What The I-Soon Leaks Show

Some of the leaks show how private operators sometimes independently–and perhaps opportunistically–exploit foreign targets, seeking a government buyer only after the data has been acquired. The chat logs from I-Soon employees demonstrate how the company, in need of cash to pad its books, conducted independent operations on the expectation (or hope) that a government customer would buy their wares. In the case presented by the chat logs, no buyer apparently materialized and such operations were the exception, not the rule. Many of the apparent victims could be tied directly to government agencies soliciting their penetration by I-Soon.

What Really Drives PRC Cyber Targeting

It remains the case that China’s national security, geopolitical, and economic objectives drive a strong set of demand signals that shape its public and private cyber operations against western targets across the full spectrum of technology and industry sectors.

Some sectors are targeted for intellectual property, scientific information, or competitive intelligence, while others fall into the military bullseye for strategic prepositioning in advance of conflict scenarios. Of course, a large effort is also devoted to domestic and overseas political monitoring, control, and repression. We see private actors like I-Soon responding with cyber solutions to meet all of these demand signals.

How PRC Political Demands Translate into Targeting Requirements

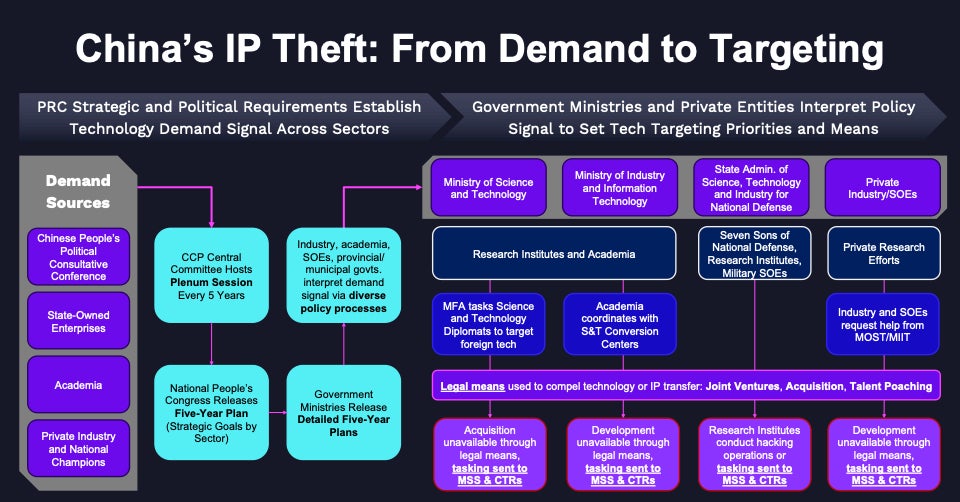

China’s approach to cyberespionage incorporates broad swaths of the party-state apparatus and translates into both legal and covert activities to meet politically-defined technology targeting requirements (see graphic below).

The top-level policy document that sets the strategic demand signal is the National People’s Congress Five-Year Plan, which establishes strategic goals by sector, against which individual government ministries release their own detailed Five-Year Plans. Different industries, academic institutions, state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and provincial and municipal governments interpret these plans and operationalize them according to their own, wildly diverse, policy processes.

The two most important ministries for technology development (and cyberespionage targeting requirements) are the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) and the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT). These ministries oversee an archipelago of research institutes and academic institutions and interact with the foreign affairs and security departments to support their efforts.

In particular, a cadre of Science and Technology Diplomats is deployed overseas to help identify and target technologies and industries of interest, while domestic academic institutions coordinate with S&T Conversion Centers to support technology transfer and indigenization activities. Meanwhile, private industry and SOEs conducting their own research efforts request assistance from MOST/MIIT and insert their own technology requirements to help shape government funding and targeting priorities.

At this level, legal means like joint venture agreements, acquisitions, and talent poaching are preferred, even if conducted with subterfuge or obfuscation via third party cut-outs. However, government research institutes, the “Seven Sons” of national defense universities, and military SOEs typically prefer illicit means. These consumers may utilize the PLA’s own hacking units or request the Ministry of State of Security (MSS) for support.

What This Means for Business Executives

China has a whole-of-government effort to capture market share in strategic industries, “seize the commanding heights” of emerging critical technologies, and reduce its external dependencies on adversaries while increasing adversary dependencies on China.

This is all in service of a grand strategy to climb and dominate global value chains, expand geoeconomic influence, and rewrite the economic and security architecture of the world system.

As the I-Soon leaks demonstrate, it isn’t just well-resourced state-actors that firms have to contend with. The fact that underpaid, moderately skilled independent hackers can achieve as much success as the I-Soon files show should be a loud wake-up call to global executives about the resilience of their security posture.