The Good

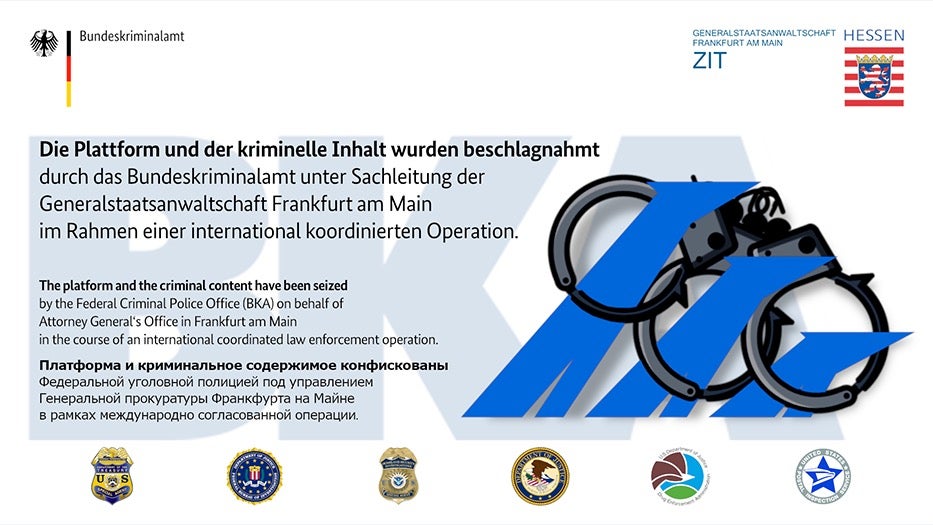

Good news this week as Germany’s Federal Criminal Police Office (BKA) announced the take down of what has been described as “the world’s largest darknet market”. Servers belonging to the “Hydra Market” were seized on Tuesday and Bitcoins amounting to the equivalent of approximately $25 million were seized. The seizures were carried out after extensive investigations by German and US authorities beginning in August 2021.

Hydra was notorious as a trading place for narcotics, stolen databases, forged documents, and hacking for hire services. Police found data belonging to around 17 million customers and over 19,000 registered traders. The Russian-language platform had been in operation since at least 2015 and is believed to have had the highest turnover worldwide for an illegal marketplace. Authorities said its sales amounted to at least $1.34 billion in 2020 alone.

Authorities also noted that the site offered a service for obfuscating digital transactions called Bitcoin Bank Mixer, intended to make investigations and analysis into criminal activities difficult for law enforcement agencies.

At the time of writing, the site’s home page has been replaced by a notice from authorities. While reportedly no arrests have been made so far, the investigation is ongoing and the seized infrastructure is still being evaluated.

The Bad

It’s been a week of bad news for mobile users with the discovery of multiple campaigns distributing banking trojans and other malware via the Google Play Store.

Researchers discovered six different apps masquerading as AV software in the Google Play Store that were found to be deploying the SharkBot banking trojan. It is thought that combined the fake AV apps had as many as 15000 downloads, and while the apps have since been removed from the store by Google, the malware remains active.

SharkBot is able to steal user credentials and banking information. The malware abuses Accessibility features on the device to lure victims into entering credentials in windows that mimic legitimate credential input forms. The data entered is then sent to a server controlled by threat actors. While the researchers did not attribute the campaign to a particular actor, they did note that SharkBot uses geofencing to identify and ignore devices located in China, India, Romania, Russia, Ukraine and Belarus.

Also this week came news of a campaign that has achieved over 50,000 installations of malicious Android software targeting banks and other financial institutions. The Octo Android banking trojan is dropped by a number of rogue apps such as Pocket Screencaster (com.moh.screen), Fast Cleaner 2021 (vizeeva.fast.cleaner), Play Store (com.restthe71), Postbank Security (com.carbuildz), Pocket Screencaster (com.cutthousandjs), BAWAG PSK Security (com.frontwonder2), and Play Store app install (com.theseeye5).

Octo is said to be a revised version of ExobotCompact and can gain remote control over devices, capture screen contents in real-time, log keystrokes and receive commands from a C2.

The Ugly

Network security vendor WatchGuard found themselves embroiled in controversy this week over a severe vulnerability silently patched last year and recently exploited by Cyclops Blink botnet.

What later became CVE-2022-23176, a flaw with a severity rating of 8.8, was fixed back in May 2021. At the time, this and other “internally detected security issues” were obliquely referred to in the company’s release notes. WatchGuard stated that certain non-specific security issues had been found by their own engineers, and were not actively found in the wild.

Importantly, the company said at the time that they were not sharing technical details about the flaws “for the sake of not guiding potential threat actors toward finding and exploiting these internally discovered issues”.

Such an approach, widely disparaged as “security by obscurity”, typically irks security researchers and WatchGuard has found themselves on the receiving end of sharp criticism since the revelation earlier this week. As pointed out by one industry professional, threat actors did indeed discover and exploit these issues, and the vendor’s lack of transparency only served to “put their customers at unnecessary risk”. Had the vendor been more transparent at an earlier stage, the argument goes, more customers would have been able to patch and security teams able to actively hunt for exploitation attempts.

Transparency with regard to software patching is always a double-edged sword for vendors. Take, for example, the contrasting approaches taken by OS vendors Microsoft and Apple, with the latter famously less transparent than the former. On the one hand, Microsoft can claim customers remain informed and in control; on the other, Apple will claim that their systems are widely perceived as “more secure”, although the very obscurity that Apple relies on makes such a claim difficult to evaluate. The reality is that whatever approach is taken by a vendor, it is always going to result in criticism when it “backfires” and threat actors compromise organizations and users.