The Good

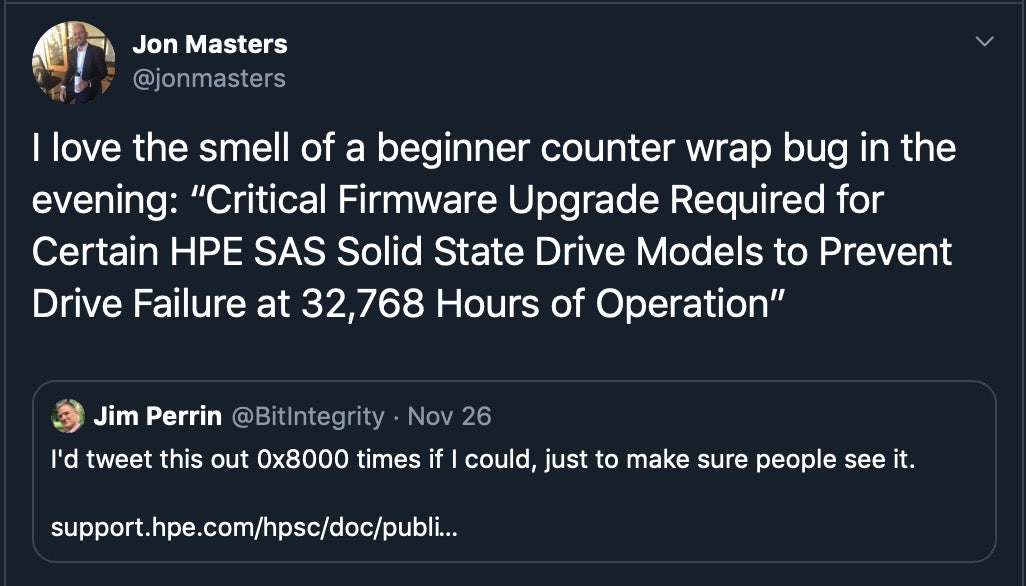

Aside from their vast resources, the one characteristic that usually marks out an APT group is stealth. Good news this week, then, as it was reported that some 12,000 Google services users were warned of government-backed threat actors targeting their accounts during the third quarter of 2019. Google’s Threat Analysis Group (TAG) keeps tabs on over 270 state-sponsored APTs and alerts users if their accounts have been hit with phishing emails, malware or other malicious methods. Users in 149 countries were sent warnings of phishing attempts, the vast majority of which (90%) were attempts to steal passwords or other credentials in order to hijack their accounts. The most heavily targeted countries were the US, Pakistan, South Korea and Vietnam. Google say the number of threats detected was consistent with the same period last year, so it’s also at least a little comforting to know that there hasn’t been any significant rise in APT attacks on Google users.

Distribution of government-backed phishing targets in Q3 (Jul-Sep 2019) Source.

The Bad

If you spend much time looking up CVEs, you might have noticed an increasing trend recently: a CVE entry exists, but it is marked as “RESERVED”, which means that details about the vulnerability have not yet been populated to the database. There’s nothing unusual in that, but according to one rival source of vulnerability intelligence, the publicly accessible CVE list has almost 1,000 new vulnerabilities listed in 2019 that are still in RESERVED status but whose details have already been made public elsewhere. Worse, there’s estimated to be around 7000 disclosed vulnerabilities this year that have no CVE ID at all. The danger here is that with such a large number of vulnerabilities missing from the CVE database, organizations that rely solely on that information for vulnerability intelligence could be leaving themselves open to attacks. Although CVE does provide mechanisms for reporting omissions, and stresses that its purpose is not to function as a vulnerability database, it’s clear by the sheer scale of missing data that MITRE has got some catching up to do if CVE is not to lose relevance.

The Ugly

It’s the kind of news that can leave you speechless, at least in polite company: a major security vendor hardcodes the encryption key that is meant to keep user data safe right into several of its products. It was revealed this week that that’s precisely what Fortinet had done, and it’s taken them 18 months to fix it! FortiOS for FortiGate firewalls and FortiClient endpoint protection software for both Mac and Windows used a simple XOR cipher and hardcoded cryptographic keys to encrypt traffic between the products and the company’s cloud services. An observer of that traffic could not only use the hardcoded encryption keys to reveal the contents of the traffic, worse they could have maliciously altered the traffic to silence malware detections or malicious URLs. At least the year and a half it took to finally patch all the affected products ensured that CVE had this one covered; see CVE-2018-9195.

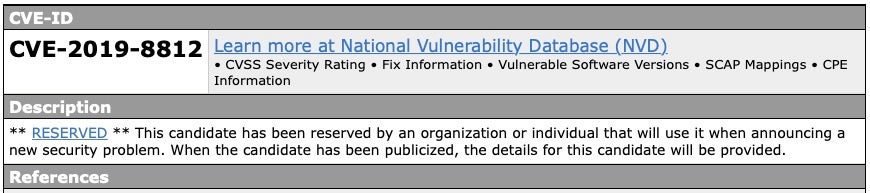

Time could literally be running out for your Hewlett-Packard Enterprise SSDs. Some of the company’s products have a flaw that will kick in after exactly 32,768 hours of operation; put another way, that’s 3 years, 270 days and 8 hours of run time. At that point, the drive will fail and all data will be lost.

HPE say that if the firmware defect occurs neither the SSD nor the data are recoverable. Worryingly, any organization that deployed multiple drives with an HPE firmware version prior to HPD8 at the same time will likely experience the drives all failing near simultaneously. The company advises that such catastrophic data loss can be avoided by applying HPE’s critical firmware upgrade without delay.